‘Brave’ leadership in think tanks, politics and universities (including some new data on vice-chancellors’ tenure)

This blog is an abridged version of a speech delivered by Nick Hillman, HEPI’s Director, to Advance HE’s summit on ‘Brave Leadership – Daring to Lead’, held in Birmingham on 5 June 2019.

Introduction

At HEPI, we publish around 20 papers a year, host around 30 events and blog nearly every day. Much, if not all of our output, is linked to good leadership.

- We published a Policy Note towards the end of 2018 on the turnaround of London Metropolitan University, written by their Vice-Chancellor between 2014 and 2018.

- Earlier this year, we published a report jointly with Jisc on cyber-security, which showed how vulnerable universities’ IT systems can be to penetration testing, or ethical hacking. Given the enormous risks of a big data breach, you would have to be a brave vice-chancellor to ignore such evidence, but in a bad way.

- A couple of weeks ago, we published a paper on staff mental health by Liz Morrish in our Occasional Paper series. We have a long record of writing about student mental health but the pressures on university staff – senior and junior – are immense too. Yet they are often overlooked. Leadership teams need to think about the mental health of their staff as well as their students – and all their staff, not just their academic staff.

But, today, I do not intend to focus on things we have already said. Instead, I plan to:

- begin by talking about my own position working in a think tank;

- move on to talk about what I learned about political leadership during my time working in Whitehall; and

- end with some remarks specifically about leadership in higher education.

Leadership in think tanks

Coming here to discuss brave leadership to a room of senior managers of huge higher education institutions – with thousands of staff, tens of thousands of students and turnovers of hundreds of millions of pounds – seems not just brave but also cheeky and a little foolhardy, given HEPI is tiny, with just four members of staff.

This means each member of staff makes up 25% of our workforce. Fortunately, we are blessed with a very strong team and HEPI’s small size provides one big advantage. We can be nimble and respond quickly. We would never turn down a project just because it is feels different to the way we’ve done things before. The planning horizon for our output is more like three to six months than the five to 10 years covered by a university strategy.

In a micro-organisation, everyone has to pitch in. You also have to work collaboratively with other organisations and, somehow, you have keep on top of all the bureaucracy, which can be the same irrespective of the size of an organisation, while not losing sight of your core functions.

For us, good leadership is partly about making us look bigger than we really are or, to put it another way, punching above our weight. People often think HEPI is much larger than it is. They phone us up and ask to speak to our press office, our human resources team or our finance department. The only thing we can do is put on a different voice and pretend we have put them through.

Another challenge, which we do share with universities, is how to measure success. As an educational charity, we know our primary purpose is to have impact: I sometimes say our goal is using evidence to reduce people’s temptation to say stupid things about higher education. But success in that endeavour is exceptionally hard to measure because we don’t have a clear counter-factual. We don’t know what would have happened if we didn’t exist (or, indeed, if we were ten times bigger).

When the Government does something we have called for, it is generally hard to know if it has happened because of what we have said or for some other reason. And when, last week, the Augar report said maintenance grants should come back, that is probably, in part, down to our consistent calls for this to happen. At least, they listed our support for the change in their report.

But, then again, they also listed the support of lots of other institutions. And if Augar is not implemented swiftly, or never implemented, does the fact that we may have influenced it in this and other ways still count as a success or not? I’ve no idea.

Measuring failure is hard too, but equally important. I know when people think we have failed because they submit a formal letter of complaint or tell us to withdraw a particular publication or even, as one professor recently did, to ‘disband’. I know we are meant to feel affronted when that happens, but – and this is really important – we do not mind if something we have said unsettles someone’s worldview.

It is amazing how often people forget the job of a think tank is to make people think. Our role is to smash echo chambers rather than reinforce them. That is not always popular. We recently lost some goodwill in Wales, for example, when we queried whether the new Welsh student support system is as progressive or affordable as the firm consensus in Wales suggests. But the primary criterion for our peer-review process has to be quality, rather than anything else.

While we are never controversial for the sake of it, our output is sometimes regarded as controversial because it challenges received wisdom or just provides a platform for a different point of view. Take the work completed for us on the comprehensive university by Tim Blackman, currently Vice-Chancellor of Middlesex University and soon to become the Vice-Chancellor of the Open University. In essence, this says if comprehensive schools are preferable to selective schools, then why not replace our uber-selective university system with open-access comprehensive universities?

Professor Blackman wants less hierarchy, more open universities and a shift away from the residential model of higher education. It is incredibly radical stuff and a piece of real thought leadership because it serves as a useful reminder that the UK model of higher education is very different to the model in many other countries. You do not have to agree with all of Tim’s ideas (and I don’t) to learn from them.

The only complaints that really hurt are those that accuse us of factual errors and, for us, it is good and brave leadership to admit and swiftly correct any that might creep into our output.

Political leadership

In political terms, your conference could perhaps have not come at a better time. Two of our biggest political parties – the Tories and Lib Dems – are in the midst of leadership elections.

During my time in Whitehall, as a special adviser to the Minister for Universities and Science, I had the privilege of watching leaders up close in Government. It was clear that, alongside a commitment to public service, the best Ministers (like the best vice-chancellors) have:

- a clear direction of travel;

- the ability to make a decision;

- an appetite for lots of hard work;

- a respect for evidence; and

- a capacity for finding a big picture among the detail.

They also display a constructive attitude, rather than a blame culture, when things go wrong. This is especially difficult because of the adversarial nature of politics. But it can be done and it is certainly an example of brave leadership. My own Minister, for example, regularly admits that his student funding reforms back in 2012 did not work out as hoped for part-time students.

If it is clear which characteristics successful politicians display, it is also clear what factors hinder good public policy. As I explained in a paper for the Institute for Government about my time as a special adviser, the single most frustrating aspect of working in Whitehall is churn.

Responsibility for higher education has journeyed around Whitehall, civil servants are told that promotion relies on changing jobs ridiculously frequently and proper records management often seems like a relic of the past. There is no institutional memory. This issue has got worse rather than better in recent years because of the pace of change in higher education.

One of the new things we are all still digesting is last week’s Augar report. Like other organisations, we have already published thousands of words on the Augar review since it first appeared last Thursday, which you can find on our website – and there is plenty more to come. [To declare an interest, HEPI’s Chair of Trustees, Professor Sir Ivor Crewe, was a member of the Augar panel, but he has had no input to our responses.]

There is plenty in the Augar report I am lukewarm to cold about, like the proposals on foundation years, freezing university income for the next few years and the over-fiddly limit on loan repayments among richer graduates.

But it is evidence-based, coherent in its overall approach and rightly recognises its starting point. Given this, I was surprised to see some of the quick-but-damning responses that it received from well-respected figures, sometimes before they had even had the chance to read it properly. It has all been a depressingly reminiscent of the way in which political parties immediately condemn any social care policies proposed by the other side as ‘death taxes’.

I recently attended a small dinner where we heard from a former Prime Minister, a former Cabinet Minister, various academics and other think tankers. The one thing everyone agreed on was that, in some policy areas, it is essential to plan for the long term.

The problem is that this is even harder than usual when no one has a clear parliamentary majority, no one knows how close or far the next election is and what Brexit actually means. Immediately dismissing the Augar report’s 216 pages of tightly-worked up policies looking far ahead is not calculated to improve policymaking. Whatever it is, it doesn’t feel ‘brave’.

University leadership

In the final section of my speech, I want to address the issue of university leadership more directly, and in particular the issue of vice-chancellors’ tenure.

There is a common perception in higher education that the tenure of UK vice-chancellors is getting shorter. The growing demands of the job, the increasing marketisation of higher education and more active governing bodies, not to mention scandals around pay, are thought to have increased the turnover of universities’ leaders. What is happening in other sectors also leaves one with the impression that top-flight appointments are for shorter periods than ever before.

But, when it comes to vice-chancellors, there is little hard evidence beyond the occasional anecdotes. So (with help from independent researcher Tom Huxley), we have tried to test the hypothesis.

You would think this would be an easy task. But it is complicated by a number of factors. For example, we had to decide which institutions to consider. We needed a time series but many UK universities have not been universities for decades. So we concentrated on the subset of UK institutions that have had university title for many decades.

We also had to decide which institutions, if any, to exclude. We left out Oxford and Cambridge from our analysis because of their past practice of appointing revolving vice-chancellors with short-term limits, as this could have distorted the results.

We then calculated the data in two ways.

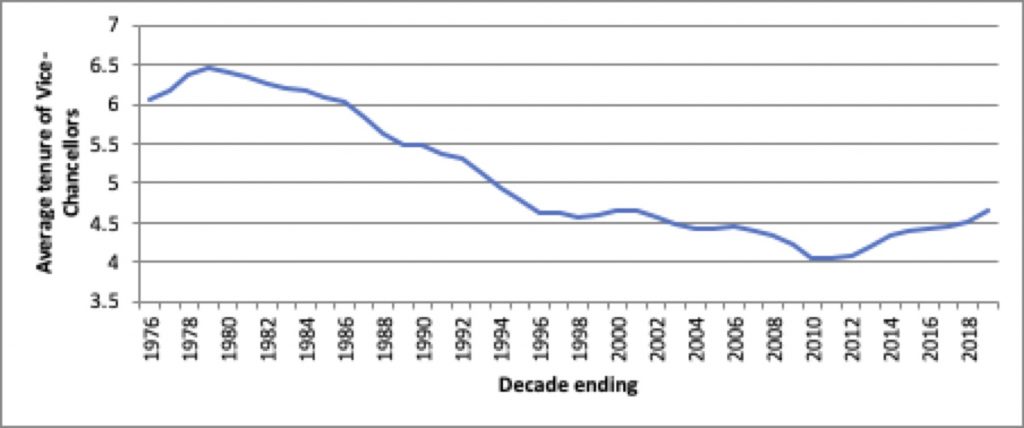

First, we calculated the average current tenure of serving vice-chancellors for every ten-year period from 1976. So, for example, the figure for 1976 in this chart shows the average tenure of serving vice-chancellors for the decade running up to 1976.

There has been a relatively consistent decline from 6.5 years in 1979 to 4 years in 2011. But, since 2012, when competition and marketisation are said to have really taken off, the average tenure number has actually been going back up a bit and now stands at over 4.5 years.

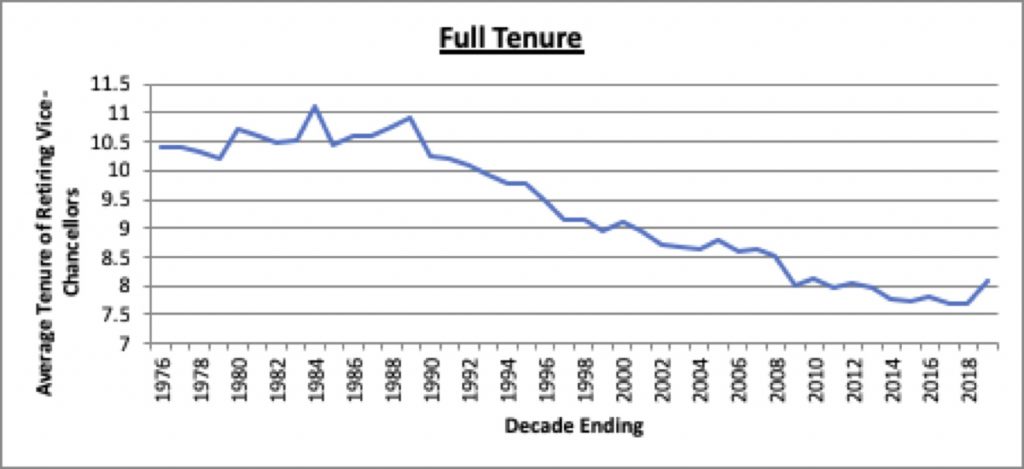

We also looked at how long vice-chancellors stay in post before they stand down. There is a similar trend, a long-term fall followed by a bit of an increase in recent times, with ‘full tenure’ rising to above 8 years once more.

This may be a blip or it may be the start of a trend. It is too early to say.

Our analysis is a long way from being exhaustive. For example, no allowance is made for the fact that some vice-chancellors go from leading one institution to leading another.

Overall, the average tenure of serving vice-chancellors is higher than the tenure for current heads of FTSE 100 companies and much higher than the tenure of either professional football managers or Government Ministers. We have had five Ministers for Universities and Science in the past five years and the last time the most senior education minister lasted more than six full years in the job was Sir John Eldon Gorst (1895 to 1902).

Conclusion

Let me end with three other points.

First, to note that the higher education sector still have some really big leadership challenges coming up, such as: pension changes; other financial pressures; and public policy challenges, including Brexit.

Secondly and more optimistically, we must not forget our sector’s successes. Institutions and their leaders, staff and students must be doing something right because, however we are judged, we do pretty well. League tables, student satisfaction rates, TEF, REF, KEF, student numbers, income and international engagement all tell a positive story.

Thirdly and finally, I want to argue that, against the consensus of opinion, we are a sector that has benefited from brave political leadership in recent times. The successes I just mentioned rest in part on brave decisions taken by politicians across the political spectrum, such as Tony Blair, Nick Clegg and David Cameron, as well as by legislators who have enshrined universities’ core strength – autonomy – in primary legislation. I like to think that is because when we explain our story well, we have a very persuasive tale to tell.

Comments

Mike Ratcliffe says:

It’s interesting that length of tenure of VCs has picked up – at least in the universities in your sample. A question – have you measured length of service at the same university? ‘Long’ serving VCs such as David Eastwood or Michael Arthur have been VCs since 2002 and 2004 if you include their previous posts.

Reply

Nick Hillman says:

Thanks Mike. The full text of the speech said: ‘no allowance is made for the fact that some vice-chancellors go from leading one institution to leading another. Among the country’s most well-known current vice-chancellors, Michael Arthur of University College London, David Eastwood of the University of Birmingham and Louise Richardson at the University of Oxford have all previously been in charge of other institutions.’ It also pointed out that excluding newer universities meant excluding some very long-serving leaders: ‘such as John Cater of Edge Hill University (appointed in 1993) and Tim Wheeler of the University of Chester (appointed in 1998), because their institutions were not universities at the start of our time series – nor even when their current leaders were first in post.’

Reply

Add comment