The road to 2.4% is long, bumpy and full of obstacles – and we may never arrive

This blog is based on last week’s speech by HEPI’s Director, Nick Hillman, to the Times Higher Education UK Academic Salon 2021.

I have been asked to focus on research and innovation and, specifically, ‘The Road to Recovery: Will 2.4% be enough’. This is a reference of course to the UK Government’s commitment to ensure that 2.4% of national income is spent on research and development (R&D) by 2027 (though I note the Scottish Conservatives put the target date a year earlier for Scotland in their recent election manifesto).

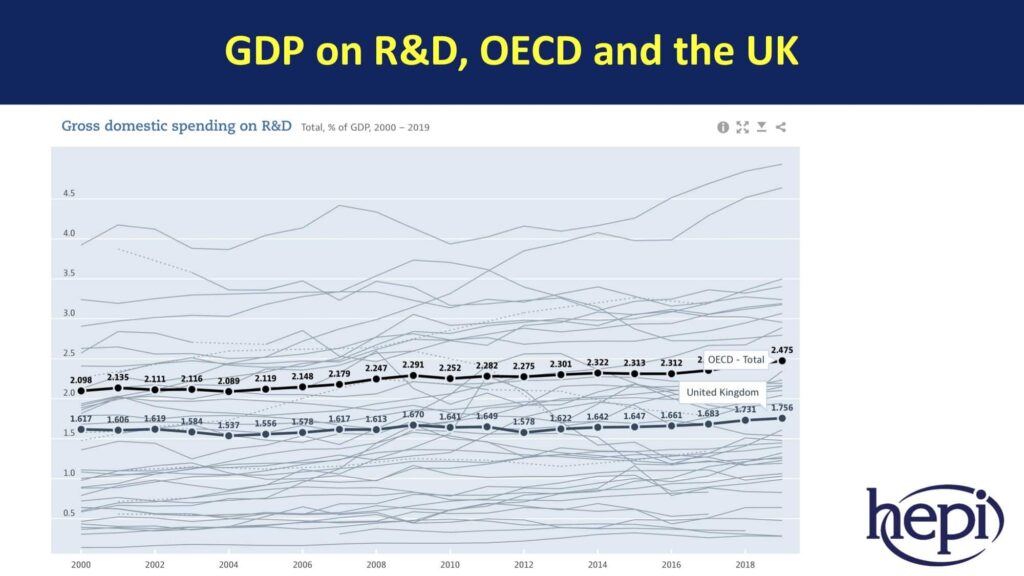

For the reasons outlined below, hitting 2.4% by 2027 will be arduous. But it would only take us to around the OECD average, which could itself go up in the intervening period. And – in the way of averages – 2.4% is much lower than in some of our key competitors, such as Israel, Korea and Sweden.

Moreover, it is actually less bold than the commitment made by the previous Prime Minister, Theresa May, in her 2017 general election manifesto, which included ‘a longer-term goal of three per cent.’ It is also marginally less than Tony Blair’s commitment back in 2004 to spend 2.5% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) on research and development by 2014.

The history of that earlier target is instructive. During the period of the target, from 2004 to 2014, the proportion of national income spent on R&D bounced around a little but there was no step change. At the end of period, the total increase in GDP spent on R&D was 0.1% rather than the promised 1.0%.

And that is far from a unique story; indeed, it is absolutely typical for targets of this type. HEPI recently published a piece by a Portuguese economist, Adão Carvalho, who has looked at similar targets across the developed world and concluded they are nearly always missed, often by a huge distance. He found:

67% of all cases studied missed the target by -40% to -100% and another 17% by more than -100% (in other words, their R&D intensity decreased over the period).

The main reasons for these failures according to Carvalho are:

- GDP grew fast and R&D spending could not keep up;

- there was insufficient public spending;

- business R&D spending did not keep up; and

- the original target was found to be unrealistic.

At HEPI, we have produced work on cross-subsidies from teaching to research that looks at the research deficit and how institutions deal with it. In 2017, we published a paper by one of our fantastic student interns, Vicky Olive, which showed a financial shortfall in research projects in UK universities of £3.3 billion. This was in part – but not entirely – made up from the fees of international students.

Some people in universities were uncomfortable with the idea of shining a spotlight on the internal cross-subsidies from teaching to research. The occasion when we asked an eminent professor and member of the House of Lords to chair an event on the issue is seared on my mind. He attacked the work, saying we were badly wrong to treat research funding and teaching funding as separate income streams because, he argued, the teaching and research functions of universities are so inextricably intertwined.

They are, of course, linked but Vicky rightly won an award from Wonkhe for her work, which was very timely. At the time the report appeared, the Government was lukewarm towards international students, and this threatened to pull the rug from some research projects by reducing the cross-subsidies from international student fees. Moreover, around the time we published the report, the Government split policy responsibility for the research and teaching functions of universities so that they came within different Government Departments, where they have remained for the past five years. It seems unwise to argue that research and teaching can never be discussed separately when that is what policymakers do every day.

It seems unwise to argue that research and teaching can never be discussed separately when that is what policymakers do every day.

Last year, we updated the work and showed the research deficit faced by universities had grown to £4.3 billion, and that proposed cuts to the income for teaching home students would leave less of the surplus from international students available to spend on research. Sadly, we published this update just as COVID was declared to be a pandemic, so it was rightly overshadowed.

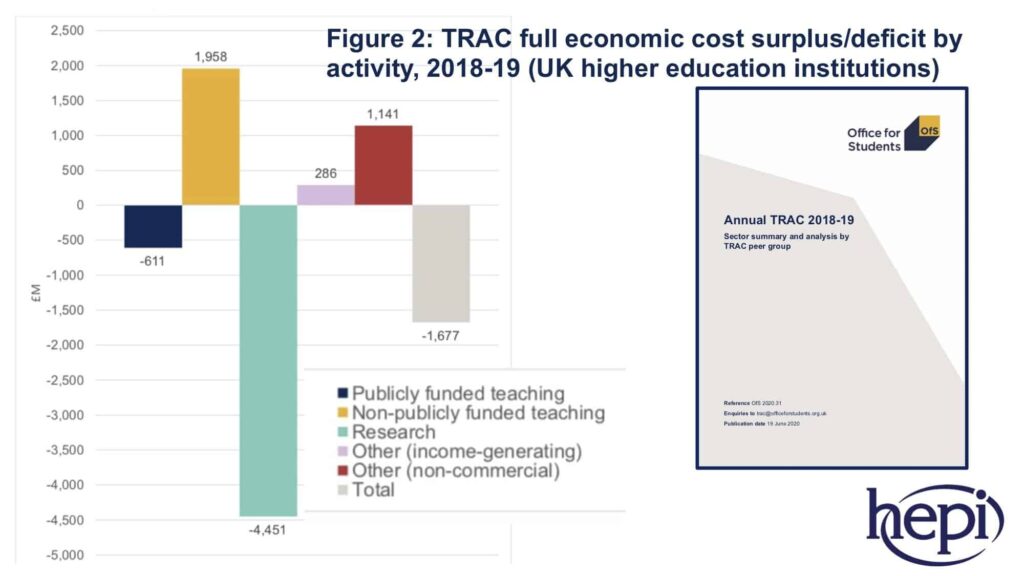

In the year since, another set of official data has been published, also somewhat hidden under the shadow of COVID, and this shows the gap between what universities actually spend on research and what they receive to spend on research has grown further to £4.5 billion.

The funding of home students covers 96 per cent of the costs educating them; the fees of international students covers a whopping 143% of the costs of educating them; but the income for research only funds 71 per cent of the actual costs.

We have, in recent weeks, seen further pressures on research budgets. The reduction in spending on overseas aid and the row over whether the UK’s future contribution to Horizon Europe should come out of the existing research budget or a new budget line confirm the pressure research budgets are under.

Perhaps it will all come good in the spending review and we are worrying unnecessarily. This could happen – for example – if the lobbying from the science and research community is able to explain how research and development spending can boost the levelling-up agenda. But in a new HEPI report we show the mixed record of past attempts to do this. It is clear from this work that we need to build a better evidence base for what strategies work when combining regional policy and R&D policy.

I have been long been worried that we have a tendency to think, as a higher education and research community, that we are good at lobbying because recent Governments have acted relatively warmly towards us. George Osborne and Philip Hammond were both committed to boosting the research base, and research budgets were insulated against the worst of austerity. But if anyone should know the difference between correlation and causation, it is the research community. Just because we have done relatively well in the past does not mean we are good at lobbying.

I often think of the important Universities UK research from a few years ago, in which the organisation Britain Thinks investigated what the public thought of universities and which concluded, ‘the majority of people rarely think about universities, largely finding the sector irrelevant’ but also that ‘Whilst not thought of spontaneously, research is seen as the single biggest benefit of universities’. Overall, the research suggested the one aspect of academic life that is the most popular has also been the most hidden.

That is perhaps the biggest challenge to confront in the weeks ahead, as the spending review hoves into view. In dealing with it, we must avoid talking more about the money than the uses to which any money is put. In the Brexit referendum we sometimes seemed to talk more about the spending received from Brussels rather than the uses to which it is put, but it is the uses of the money that transforms lives.

I am one of millions of people proud to have had the Oxford Astra Zeneca jab. Perhaps the jabs alone will change how we talk about research. I certainly hope so. But that may only happen if we continually remind people of exactly why life was able to return to normal after the crisis is finally over.

Comments

Add comment