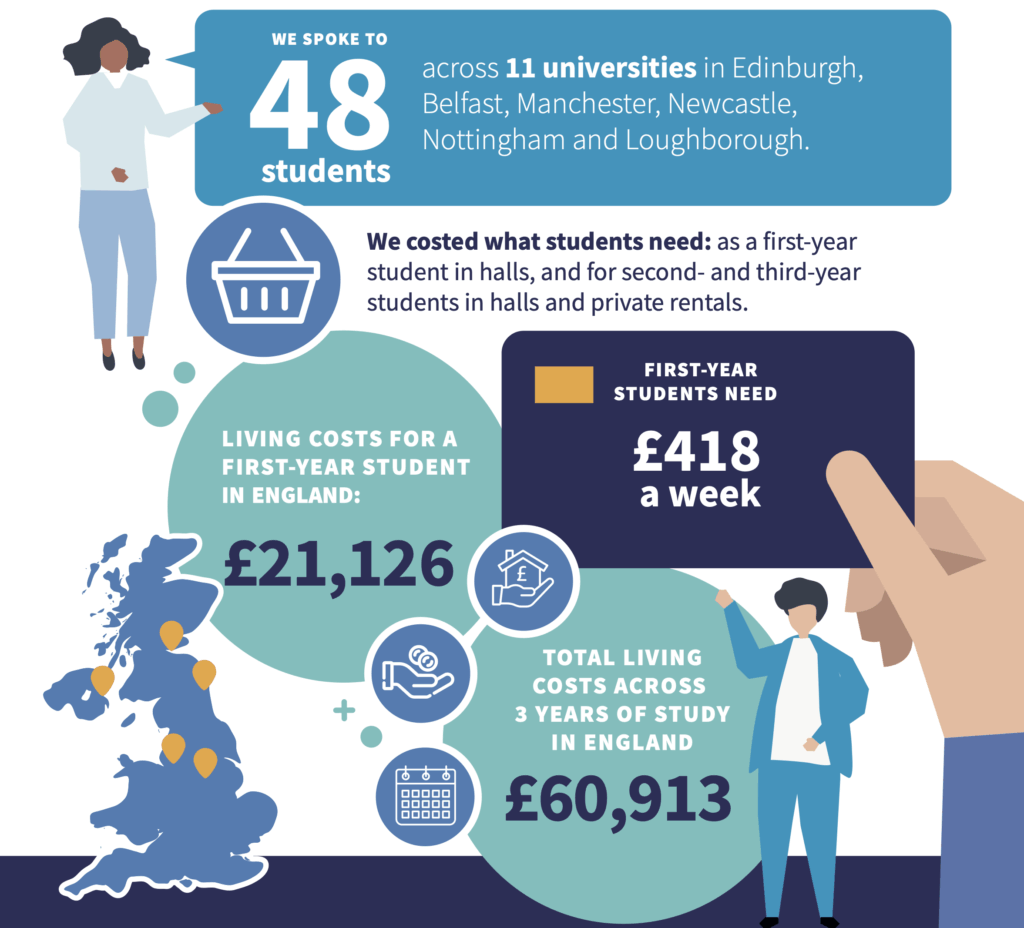

Maintenance loan in England now covers just half of students’ costs

- To have a minimum socially acceptable standard of living, a student needs £61,000 over the course of a three-year degree, or £77,000 if studying in London – all excluding fees.

- First-year students face higher costs than other students, due to one-off ‘setting-up’ costs (eg buying a laptop) as well as ‘settling-in’ costs (such as freshers’ week activities).

- For students in England, the maximum annual maintenance loan available to people from low-income households is £10,544 – this covers just half the costs faced by freshers.

A new report from HEPI, TechnologyOne and the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University shows how much first-year students need for a minimum socially acceptable standard of living that covers the basics and allows full participation in university life.

The Minimum Income Standard for Students is based on focus groups with students in university cities. These were used to price up a minimum basket of goods and services for students.

The report focuses in particular on first-year students in Purpose-Built Student Accommodation, such as halls of residence, but the results can be used to calculate the total costs of a full-time degree.

Key findings:

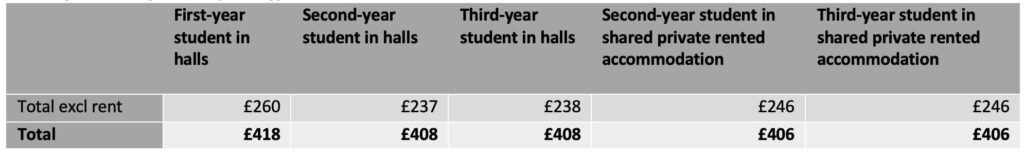

- Excluding rent, first-year students living in halls need £260 a week on average to cover living costs. With rent, students need an average of £418 a week.

- First-year students have a somewhat higher weekly budget than other students because there is a ‘first-year premium’ made up of: ‘setting-up’ costs – such as buying a laptop, kitchen equipment, bedding and other items needed throughout a degree; and ‘settling-in’ costs – such as freshers’ week activities and to build connections with other students while learning to live independently.

Average weekly costs for different students

- Costs vary around the country, meaning annual living costs for first-year students are £21,126 a year in England, £18,244 in Northern Ireland, £19,836 in Scotland, £20,208 in Wales and £24,900 in London. In London, rent makes up nearly half (46%) of students’ costs.

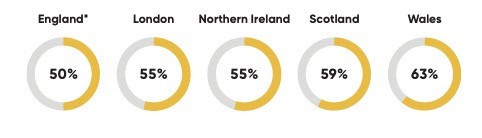

- For students domiciled and studying in England, the maximum maintenance loan (£10,544), which is only available to people from low-income households, covers just half (50%) of a first-year student’s true costs.

- Students living and studying in Scotland have 59% of their costs covered by the maximum maintenance support and those in Wales have 63% of their costs covered.

Proportion of first-year students’ costs covered by maximum maintenance support

- Those facing the biggest shortfalls are students from Scotland studying in London, as they receive no London weighting – their maximum maintenance support covers only 46% of their costs, leaving a shortfall of £13,500 a year.

- We also estimate the full living costs for a student over their entire degree. For a three-year degree, a student studying in England (outside London) will need around £61,000 to reach a minimum socially acceptable standard of living. A student studying in London would need around £77,000.

Total living costs, three-year degree, student who rents privately after first year

- These figures exclude tuition fees (generally £9,250 in England and Wales in 2024/25 but rising to £9,535 in 2025/26). With fees, a standard three-year degree in England can now cost around £90,000, or over £100,000 if the course is in London. Four-year courses cost commensurately more. However, home students can generally receive a tuition fee loan to cover the full amount of fees.

- The report also looks at how many hours of part-time work a student would need to do to reach the minimum acceptable standard of living: even when in receipt of the highest levels of maintenance support, students in England must work over 20 hours per week in term-time and vacations at the National Minimum Wage to meet the basic standard of living.

- The report recommends redesigning student maintenance support on the bases of simplicity, transparency, independence, sufficiency and fiscal neutrality.

In the concluding section of the report, Josh Freeman, one of the authors of the report, writes:

‘These findings demonstrate three serious risks to UK higher education: access to higher education becomes more unequal, the quality of the student experience suffers and the sustainability of the sector is put at risk.

‘The harm students currently face cannot be overstated. Too many students are struggling to cover their basic costs, let alone participate fully in higher education. It is not only good policy: there is a moral imperative to give students a fair chance of succeeding and thriving in higher education.’

Nick Hillman OBE, the Director of HEPI, said:

‘It is regrettable that we have had to calculate these numbers as, in an ideal world, there would already be a deep understanding of the true cost of being a student in the corridors of power. If there were, then student maintenance support would likely better reflect the actual costs of studying in 2025.

‘The total living costs while acquiring a degree now top £60,000 in England if the student is to receive the full benefits of higher education, and they are over £90,000 once tuition fees are included. In London, the total cost of a degree is over £100,000. Maintenance support is currently woefully inadequate, leading students to live in substandard ways, to take on a dangerous number of hours of paid employment on top of their full-time studies or to take out commercial debts at high interest rates.

‘We hope our results will lead to deeper conversations about the insufficiency of the current maintenance support packages, how much the imputed parental contribution should be and whether it is unreasonable to expect most full-time students to have to find lots of paid work even during term time. This new research will be of particular benefit to any policymakers, professors or parents trying to understand the stresses of being a young person today.’

Cheryl Watson, Education UK Vice President at TechnologyOne, said:

‘This research reveals a widening gap between the expectations students bring to university and the reality they encounter. With rising living costs and limited financial support, students are facing increasing challenges – and institutions are under growing pressure to deliver on the promise of student success.

‘We recognise that higher education institutions are working incredibly hard, often under complex and resource-constrained conditions. Staff are committed to supporting students, but without the right tools and insights it’s difficult to intervene early or drive meaningful outcomes.

‘Outdated systems can limit visibility and responsiveness. Supporting student success today requires more than incremental upgrades – it calls for modern, connected technology that gives institutions a full view of the student journey and enables timely and data-informed action.

‘As a partner to the sector, we believe technology should be seen not just as a back-office function, but as a strategic enabler of student success — helping universities enhance engagement, wellbeing and performance at scale. In a rapidly changing landscape, where the student experience is being redefined, institutions have a powerful opportunity to lead with innovation.’

Prof Matt Padley, Co-Director of CRSP and one of the authors of the report, said:

‘This new research gives us a clear picture of what students need, as a minimum, to cover the basics, but also to be able to participate in university life. Participating in the student experience – being able to socialise with friends, as well as joining clubs and societies – is important across all years at university.

‘But it is especially important in the first year to make these connections and establish friendships. Finding your feet as a first-year student is difficult enough without having to worry about balancing the costs of “settling in” against the cost of rent and food.

‘Having this clear evidence about the minimum needs and costs facing students throughout their time at university gives us a starting point for a much-needed conversation about the financial support currently provided to students. But it also points to the importance of discussing and addressing the key costs, outside of tuition fees, faced by students. Ensuring all students can meet their minimum needs is not just about increasing levels of financial support but is also crucially about looking at what can be done to reduce costs.’

HEPI and TechnologyOne will be hosting a free webinar on the cost-of-living for students and maintenance support levels on Wednesday, 10 September 2025 at 12.30pm. Register here.

Notes for Editors

- HEPI was founded in 2002 to influence the higher education debate with evidence. We are UK-wide, independent and non-partisan. We are funded by organisations and higher education institutions that wish to support vibrant policy discussions, as well as through our own events. HEPI is a company limited by guarantee and a registered charity.

- TechnologyOne is a global Software as a Service (SaaS) company. Their enterprise SaaS solution transforms business and makes life simple for universities by providing powerful, deeply integrated enterprise software that is incredibly easy to use. The company takes complete responsibility to market, sell, implement, support and run solutions for customers, which reduce time, cost and risk.

Comments

Diana Harrington says:

As someone who went to University from 1978 to 1983 with no fees to pay due to family income being low, I find this very depressing. Education, and getting as much of it as possible was my parent’s ambition for me. Not wealth acquisition. It was the most important period of my life, no doubt. It should be a right in a progressive society.

Reply

Ron Barnett says:

So far as students are concerned, it is the maintenance issue that matters, and not the fee issue.

I do hope that HEPI can use its influence in the corridors of power to get this simple point across. There is political mileage in it for the present Government. (Perhaps here, in this matter, is an opportunity for HEPI?)

PS: Missing from the headlines is the inevitable tendency now for students to continue to live with their parents – which is posing additional social costs.

Ron Barnett

Reply

Stephen Smith says:

I find it very hard to believe that first year students need £260/week to live on. £85/week on food alone? 48 students is a very small sample and it doesn’t seem enough to reflect the true average.

Reply

James Seymour says:

A few trusted websites have useful cost of living tools such as the one created by Complete University Guide and WhatUni.com:

https://www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk/student-cost-of-living-calculator

Reply

Sarah says:

The methodology is flawed they have worked this out on 52 weeks not the 30 weeks of university terms. Most students go home in the holidays so their costs are then lower (although not rent if renting a house).

Reply

Add comment