Languishing at Senior Lecturer: Striving, Surviving, or Stuck?

This HEPI blog was kindly authored by Karen Lander, Senior Lecturer in Experimental Psychology at the University of Manchester.

For many academics, reaching Senior Lecturer status is a milestone – but what happens when you stay there for years, unable to break through to the next level? Some see it as a respectable career achievement with an established role within higher education. Others feel stuck in an academic system that demands more but rewards less.

The reality? Academic promotions may be perceived as being increasingly difficult and the pressure to strive for professorship can feel both exhausting and unending. So, is Senior Lecturer a fulfilling end goal, a stage for resilience, or a sign of an academic system failing its scholars?

The UK vs. US Divide: Who Gets to Be ‘Professor’?

Unlike the UK, where professor is a distinguished rank, the US academic system grants the title more broadly. In the UK, academic titles typically follow a hierarchy: Lecturer (entry level) – Senior Lecturer (mid-career) – Reader – Professor (elite academic status). Reader is less common, as many academics make the leap directly from Senior Lecturer to Professor. In contrast, in the US, academics are referred to as Assistant Professor – Associate Professor – Full Professor. Confusingly, these terms are also sometimes used in the UK, mostly in some newer (post-1992) universities. Here, the distinction between ranks is still as important (certainly for those within this system) but the ‘Professor’ title is less exclusive. This more generic use of the term ‘Professor’ adds confusion for people looking in, less familiar with the way the Professor title is used and assigned.

In the UK, making Professor is usually only awarded to those deemed exceptional in their fields. Whereas in the US, being a Professor is standard, with tenure usually being a more pertinent marker of success. For UK academics, this transatlantic distinction may make career progression even more frustrating, given that their US counterparts are professors far earlier in their careers.

The Reality of being a Senior Lecturer

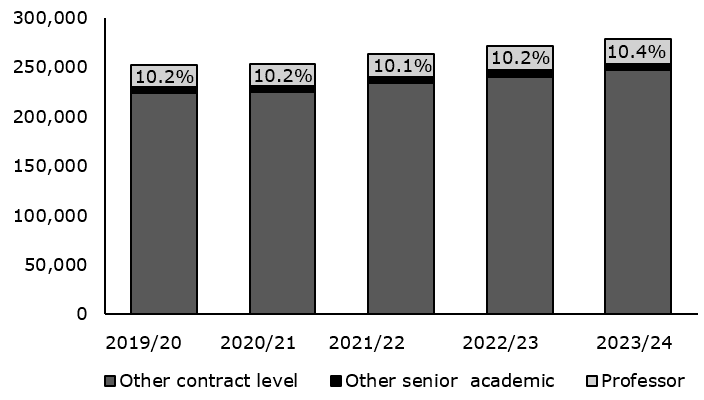

In UK academia, a Senior Lecturer will likely have demonstrated themselves in teaching, research, scholarship and university service (with the pattern of contribution depending on contract type) with many finding themselves stuck in this permanent middle tier. Indeed, according to HESA data, currently only about 10-12% of academics currently have the title of ‘Professor’ (see Figure 1). For the majority, then, career progression stalls at Senior Lecturer or Reader Level

Figure 1: Stacked column bar chart showing the number of Higher Education academic staff by year (HESA data; see https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/28-01-2025/sb270-higher-education-staff-statistics). The percentage of Professors are shown. Note: some ‘senior academic’ staff members may also have the title ‘Professor’ taking the estimated total up to a maximum of 12%.

Several factors contribute to this, including high competition, specific promotion criteria, and individual career choices. In addition, against the current economic background, a number of UK universities have paused all promotion applications and the focus on ‘surviving’ is increasingly important. Finally, gender disparities may prolong academic progression for women, who take, on average an additional 6 years to become Professor compared with their male counterparts (Harris et al., 2024).

So, while some Senior Lecturers remain content in their existing roles, others battle an uphill struggle for recognition.

Striving: The Fight for Professorship

For some, professorship remains the ultimate goal. This title typically functions as an external indicator of academic success, institutional prestige, and influence in one’s field. Yet, earning this title requires significant effort. Universities set demanding criteria for promotion, which – depending on your academic focus or contract type – is likely to include high-impact publications in leading academic journals; a track record of large-scale external research grant success; long term excellence in teaching, scholarship and mentorship; and educational leadership through committee work, departmental influence, and public engagement (Mantai & Marrone, 2023).

Yet, even meeting these criteria doesn’t guarantee promotion. In academia, the number of professors is generally not fixed and fluctuates over time due to institutional restructuring, shifts in student enrolment, budget allocations and evolving academic priorities (Gappa, Austin, & Trice, 2007). Some struggle with institutional biases, while others lack the confidence and mentorship necessary to push themselves forward.

Surviving: Satisfaction of Staying Put

Not everyone desires a professorial title, and for many, Senior Lecturer is a satisfying career stage. It allows for meaningful student interaction and continued research without the pressures that come with high-level institutional leadership.

Yet survival mode kicks in when people are being made redundant, expectations keep rising, workloads expand, and the pathway forward remains unclear. Senior Lecturers often absorb significant administrative burdens as universities assign management tasks onto mid-career academics (Bosanquet, Mailey, Matthews & Lodge, 2017). This administrative burden may also come with mentoring responsibilities without corresponding leadership recognition, and teaching-heavy roles, with less time for research advancement or scholarship. Without clear incentives for promotion, frustration builds.

In some extreme cases, long-serving Senior Lecturers may find themselves working harder yet missing out on funding, decision-making power, and institutional influence.

Stuck? The Changing Landscape of UK Academia

There are certainly more professors now than there used to be, but the road to becoming a professor is still long and confusing. Competition is fierce and promotion criteria are often somewhat vague. Coupled with shifts in universities’ funding models, many highly capable scholars never achieve Professor status.

Further with the shift toward managerial roles, professors are expected to handle greater administrative responsibilities, deterring some academics from pursuing promotion at all. For those in Senior Lecturer positions, this shift makes career progression feel more like an exception than an expectation. And as gender and age disparities persist, some find themselves wondering whether striving for Professor is even worth it anymore.

Is Striving worth It?

If you’re a Senior Lecturer, the key question is whether promotion matters to you. If professorship remains your goal, it requires strategic networking and institutional visibility, securing high-profile research funding, leadership or scholarship influence beyond your department and a clear narrative of impact.

Yet for those feeling satisfied where they are or exhausted by the pursuit, the alternative is to find meaning beyond titles. Some choose to focus on teaching innovation and mentorship or drive other aspects of their role without chasing formal recognition.

Ultimately, Professorship remains a highly selective process with evolving criteria. And for those who remain Senior Lecturers. It may be time to redefine success in academia. For me? I keep striving.

Comments

Xenossf says:

And yet, Senior Lecturers can rest comparatively easy in the knowledge that, short of their departments being shuttered, they still have something resembling job security. Not sure complaining about one’s good fortune amounts to a ‘serious issue’ when most of their junior colleagues can’t even secure basic teaching contracts!

Reply

James Fuller says:

It’s very troubling that all Hogwarts teachers just get to be professors. Who is regulating this area of the sector?

Reply

Prof David Bignell says:

My progress to a Chair in London University was facilitated by unpaid leave, when I took temporary positions in Malaysia, Japan and Australia. No teaching and no administration, so I was able to publish my research in numerous papers. In the UK, in most institutions the teaching and admin loads are now crippling, so no wonder promotion is slow. If you are good at these things, you will get more added to your duties. External scrutineers of your Department will then criticise the lack of research.

Reply

Don John Omale says:

Insightful essay. Well done 👏 👌

Reply

David Maltby says:

Very insightful analysis. As a Reader I took redundancy and got professional satisfaction elsewhere. Ironically, I returned as Visiting Professor! Must be even worse these days given the mess the system is in. I suspect that patronage, internal politics, self-confidence, personal drive, ability not to annoy those who control your future, and luck still play an important role in securing professorial status.

Reply

J Evans says:

Thanks for this. I think promotion criteria is easily abused. I see SLs getting professorships based on research and teaching who aren’t we known even nationally, have demonstrated little leadership at institutional level and frankly EDI targets are interfering with objectivity. Many SLs are demonstrating far more leadership skills and are in roles way beyond some professors. T

Reply

JOHN KARADELIS says:

There is plenty of discrimination plus a number of other reasons why most able academics stick to senior lecturer scale.

Progression and promotion should be open and transparent as it is in most European institutions.

Top management should not be there “for ever”, especially when they have nothing to offer anymore and become a burden.

I wish there was a body that they would oversee all the above and make appropriate decisions.

Reply

Masi Noot says:

Considering the role of ethnicity and race in further reducing professorial promotion chances, not discussing it is a conspicuously odds abscence in this article. In fact, being women and black must hold the lowest chances possible.

Reply

Andy Long says:

Thanks – really interesting article and certainly food for thought.

One point for clarification: I believe titles such as “Associate Professor” are now used widely in pre-92 universities, indeed they may well be more common in those institutions than in post-92s. For example they are used by many Russell Group universities including Oxford, Cambridge, LSE, UCL, Birmingham and Nottingham. My understanding is that the change was motivated by a desire for consistency with international norms.

Reply

kamir bouchareb st says:

thank you

Reply

Add comment