Growth is possible in international student recruitment for UK universities

This blog was kindly authored by Viggo Stacey, International Education & Policy Writer at QS Quacquarelli Symonds. It is the fourth blog in HEPI’s series responding to the post-16 education and skills white paper. You can find the first blog here, the second blog here, and the third here.

The post-16 education and skills white paper, released last week, outlines how the UK government aims to ensure that universities can attract high-quality international talent and maintain a welcoming environment for them.

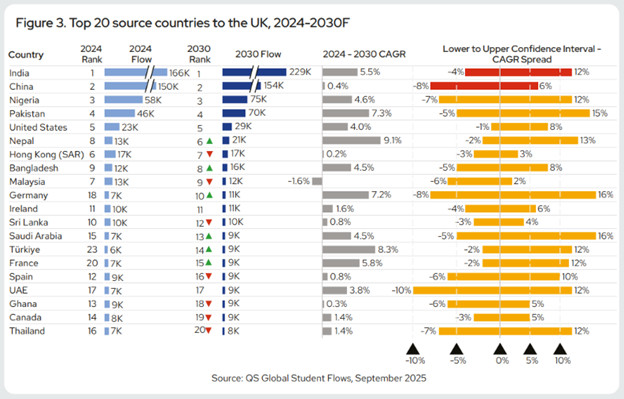

New data in the QS Global Student Flows: UK Report projects that international student enrolments will grow 3.5% annually to 2030. While this is ahead of anticipated growth in the US, Australia and Canada, where projections are between 2% and –1%, the forecast for the UK is significantly slower than the double-digit surge of 11% between 2019 and 2022.

When the Secretary of State for Education and Minister for Women and Equalities, Bridget Phillipson, spoke about transformation in education in the UK on Monday, she may also have been speaking about the international education system worldwide. International education is changing, and the UK is facing unprecedented competition from international peers. Emerging study destinations are increasingly appealing to prospective international students. India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, and South Korea are just a handful of examples of places heavily investing in internationalisation, campus facilities, and English-language programmes. Additionally, unpredictable geopolitics, economic shifts and demographic changes are making the job of international student recruiters at universities in the UK extra challenging. In such an unstable global landscape, the QS Global Student Flows: UK Report urges universities to plan for a range of scenarios.

What can institutions and the sector do?

The latest HESA figures available are from the 2023/24 academic year. No other business would rely on such outdated figures. So why would a government make policy decisions based on them? And why would a university?

This new QS report identifies key areas where UK universities can expect to see heightened global student flows in the future and how they can best continue to attract international talent and skills.

Enrolments from South Asia are expected to rise from 245,000 in 2024 to 340,000 by the end of the decade, and Africa is projected to be the UK’s second-fastest-growing region, with an annual growth rate expected to reach 4-5%.

In Asia, growth is more mixed. Enrolments from Malaysia are expected to decline, Singapore is likely to remain stable, with places such as Thailand and Indonesia seeing upticks.

Student numbers from the Middle East to the UK are projected to slow to about 1% annually in the years to 2030, compared to the nearly 5% average growth recorded between 2018 and 2024.

However, enrolments from Europe, which have declined after Brexit on average by more than 8% annually between 2018 and 2024, are expected to grow modestly at around 2.5% through to 2030.

Leveraging their strong reputations, quality of provision, as well as the important Graduate Route visa (some 73% of international students are satisfied with the pathway), UK universities can drive growth, especially in Africa and South and Southeast Asia.

What can the government do?

The government has reiterated that it wants to maintain the UK’s position as one of the world’s top providers of higher education; attract the best global talent; and project the UK’s international standing through strong international links and research collaboration.

It rightly acknowledges that volatility in international student numbers is one factor driving financial pressures in higher education. But if it is to succeed in its ambitions, universities need the right support and policy landscape.

Shortening the length of the Graduate Route visa to 18 months from two years and the possibility of hiking fees for students through the proposed International Student Levy could deter international students from choosing the UK.

Yet UK government policy is not the only factor limiting the potential of the UK.

Universities are grappling with heightened investment in higher education in key student source countries, with domestic provisions increasingly competing for quality students.

Prospective students are weighing up their options in unpredictable economic landscapes and governments are increasingly seeking to retain talent rather than encourage them to study overseas.

Examples of this include the UAE making criteria for joining its outbound mobility scholarship programme tougher; Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambition to create an “education system in India that youngsters do not need to go abroad to study”; China, traditionally the top source for international students, is gradually transforming into a study destination in its own right.

The pressure is on higher education providers in the UK – they are already diversifying income streams. But this report shows that there are opportunities for growth. UK universities just need to identify what is possible for them.

The QS Global Student Flows: UK report is available here.

Comments

Samuel Cameron says:

Anything is possible that does not defy the laws of physics.

Reply

Add comment