Three hot takes you may have missed from the Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper.

This blog was kindly authored by Rose Stephenson, Director of Policy and Strategy at HEPI.

It is the ninth blog in HEPI’s series responding to the post-16 education and skills white paper. You can find the others in the series here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

There have been oodles of column inches already published about the Post-16 White Paper, and many have rightly focused on the headlines: increased tuition fees, a return of targeted maintenance grants funded by an international students levy and a move towards more specialist institutions.

In this blog, I want to dive beyond these headlines, as the paper contains a number of further bold policy proposals, some of which could be transformational for the sector.

Break points

The White Paper places a strong focus on flexible learning, including a greater number of Level 4 and 5 qualifications. There is a specific target of at least 10% of young people going into Level 4 or 5 study, including apprenticeships, by 2040. Clearly, the Government wants to see more movement in this direction from the sector, adding:

We need to build clear and well-understood pathways at these levels [4 and 5], underpinned by qualifications that are easier to study close to home, which are both modular and flexible.

In terms of higher education providers, the Government sets out:

We will expect providers to offer more flexible, modular provision and strengthen progression routes from further education into higher education, supported by transferable credits. We will consult on making student support for level 6 degrees conditional on the inclusion of break points in degree programmes. This marks a significant shift towards a more inclusive and adaptable model of learning, empowering individuals to tailor their educational journey.

There is little detail, but it reads to me that the Government will consult on a proposal that students will only be able to access student loan funding for institutions that offer ‘break points’ at Level 4 and 5 of a full three-year degree.

This was also a recommendation from the Augar report, which outlined:

… providers with degree-awarding powers will be required to offer them [level 4 and 5 qualifications] as ‘exit’ qualifications if learners choose to leave a course early.

In my experience, most institutions now do this. If a student wants or needs to finish their studies at the end of their first year, for example, (providing they have passed the required modules), the institution would offer to award them with the Level 4 qualification that recognises their learning to date – most likely a certificate of higher education. However, ‘CertHEs’ are only routinely awarded ‘mid-degree’ if a student withdraws, and many students don’t know that there is an option to take a qualification at the end of their first year. One might wonder if providers could maintain this ‘consolation prize’ status quo. However, the paper goes further, stating:

The introduction of break points will ensure that learners are acquiring vital, usable skills in every year of higher education. It will give them the option to break down their learning, achieving a qualification at level 4 after the first year and level 5 after their second year of studies, while also ensuring institutions are incentivised to support those who wish to continue their studies. This will enable young people to ‘stay local and go further’ by connecting local provision at level 4 and 5 with internationally recognised degree-level providers, unlocking opportunity and ambition across every region.

I am reading between the lines here, but it looks as though providers may be expected to award students at the end of each year of learning, increasing awareness of stackable, flexible learning, and potentially a knock-on increase in student mobility between institutions. As with much of this White Paper, we await the details.

Accommodation

The white paper outlines:

We will work with the sector and others so that the supply of student accommodation meets demand, including increasing the supply of affordable accommodation where that is needed. We will work with the sector, drafting a statement of expectations on accommodation which will call upon providers to work strategically with their local authorities to ensure there is adequate accommodation for the individuals they recruit.

Firstly, this statement is a little ironic given that the Renters Reform Act that has just passed through parliament is likely to reduce small (generally one to two bedroom) off-street student housing provision – as outlined by Martin Blakey in his blog.

This feels woolly to me. What levers does the Government have to pull to increase the supply of affordable accommodation for students? If it does have any, why have these not been pulled already? The main driver of expensive student accommodation is that there are not enough houses (for the general population as well as students), allowing rents to be driven ever higher. Providers working strategically with local authorities won’t deliver more housing stock. (Unless the magic house bush grows alongside the magic money tree?)

We’ve seen a ‘Statement of Expectations’ previously, delivered by the OfS in relation to sexual harassment prevention and response on campus. This was an evaluated stepping stone on the way to regulation. Could there be an increased expectation on institutions to provide affordable accommodation as part of future regulation? A sensible ideology, perhaps. After all, we know students want and need cheap places to live. But given the financial position of many institutions, the resulting pause in capital building projects, the increase in commuter students and the impending decline in 18-year-old population numbers, I can’t see many subsidised student flats being built anytime soon.

Apprenticeship ‘units’

We have known since before the 2024 General Election that Labour wanted to expand the Apprenticeship Levy to become the Growth and Skills Levy. We see some more detail about this in the paper:

We want employers to be able to use the levy on short, flexible training courses.

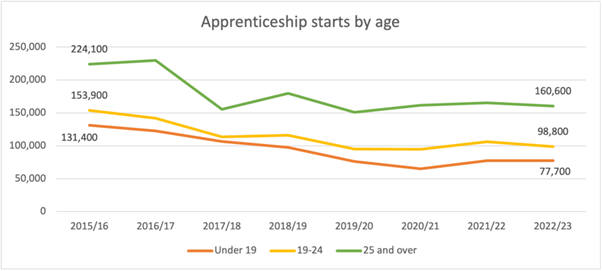

Currently, apprenticeships are funded by the apprenticeship levy. Businesses with a pay bill of over £3 million pay 0.5% of this into the levy ‘pot’. Businesses can then use the levy fund to cover the cost of training apprenticeships. Since the introduction of the levy, the number of apprenticeship starts has fallen, and the age profile of apprenticeships has changed. Since 2015, proportionately more apprenticeships have been started by those aged 25 or over.

Source: Department for Education, Apprenticeships and traineeships data

So – the apprenticeship levy was, unintentionally, a good policy for lifelong learning; businesses wanted to reinvest their levy costs into their business and found that an effective way to do this was to upskill colleagues already employed in their organisation, often on higher or degree apprenticeships. The flip side of this meant that the intended outcomes of the policy, supporting school and college-leavers into apprenticeships, were stymied.

To tackle this, most Level 7 Apprenticeships were defunded, with the aim of pushing funding back towards younger learners and lower-level apprenticeships. So the move to ‘apprenticeship units’ feels undermining of this aim. Again, this is likely to be great for lifelong learning. Employers will be able to upskill their workforce, initially in ‘priority areas’ such as artificial intelligence, digital and engineering.

There is a limited pot of growth and skills levy funding, which has been fully or overspent for the last two academic years. So if the Government wants to increase apprenticeships for younger learners, it will need to expand this pot, and potentially ring-fence some of this. The potential for a bigger pot is hinted at:

We will work with businesses and employers over the coming months to ensure that the growth in skills levy author is developed to help meet their needs and incentivise further employer investment in training.

However, ring-fencing is not mentioned. The Government will need to put some guardrails in place here if they want to meet their target of two-thirds of young people going to university, further education or a ‘gold standard apprenticeship’ by the age of 25.

Conclusion

So, while some of these statements are bold, remember that White Papers set out proposals for future legislation; there is a long way to go before legislation is in place. Further, there are several places in the white paper where the Government doesn’t specifically propose legislation; instead, there’s a sense of just asking the sector nicely. This is all well and good, but in times of severe financial constraint, asking institutions nicely to take steps that will cost them money is unlikely to yield results.

Comments

Paul Woodgates says:

Thanks for this – very interesting reflection on some lesser-noticed elements of the White Paper.

I am particularly surprised that the first of the issues listed here – break points in degree programmes – has not received wider comment. The implications of this if the sentiment behind it becomes real policy (big if…) are profound. If even some students apply for a course in the expectation that they will study for one year in order to gain a qualification then later decide if they want to undertake a second and ultimately a third year to gain higher qualifications, the financial implications for universities are huge (though not all negative). It suggests large first year cohorts, smaller second years and still smaller third years. It may perhaps make it much more normal to change provider between the years of a course.

It also completely changes the debate around continuation and would require a rethink of the metrics used to measure retention. If a student’s decision to leave after one or two years became a perfectly valid exercise of student choice in line with government’s policy intent – rather than “drop-out” – presumably it would cease to be a cause for regulatory sanction.

Reply

Replies

Rose Stephenson says:

Great to hear from you Paul. Yes, I agree. If the LLE is enacted as the Government would like it to be, continuation – as far as I can see – will have to go out of the window. Very early thinking from the OfS looked at continuation over a longer period (e.g. 5 years) but I hope this thinking has moved on, as it undermines any innovation that would come with the shift to an LLE focused future.

Reply

Jonathan Alltimes says:

Given the financial pressures, is the intent of the breaks in degree programmes to move universities towards a continental model of extended higher education or like the Open University, where it is normal for degrees to require several years to complete?

Given the rate expansion of numbers way ahead of what was foreseen when the 50% widening participation target was set, the student accommodation crisis is likely to continue for many years into the future as the supply of developers’ plots, the supply of tradespeople, and limited planning permission continues to be constrained. All of which raises the price of accommodation for local residents. Building upwards does not necessarily release accommodation for students, whose effective demand is restricted by the size of the student loan.

The supply of apprenticeships has been thought about for many years and is not going to be provided until apprenticeships are made mandatory for employers, as there is no cost advantage of a protracted period of training for 16+ students, who may not complete the training or leave after the training, when an employer can recruit from international labour markets for mature ready-to-work employees. Obviously, pay is an issue for retaining apprenticeships.

Reply

Pete says:

It’s not clear how ambitious the government is on its aim to “enable young people to ‘stay local and go further’ by connecting local provision at level 4 and 5 with internationally recognised degree-level providers, unlocking opportunity and ambition across every region”.

If they were being very ambitious, the government could aim to move towards the Scottish system, where around 60% of entrants to full-time undergraduate study study sub-degree qualifications in Colleges and a large proportion of university entrants do so via articulating from Colleges after completing an HND or HNC. I was surprised there was not more explicit mention of the Scottish model or even articulation (which did feature in Labour’s Opportunities Mission document back in July 2023). That would certainly be good for the Treasury though maybe not for equality of opportunity…

Reply

Add comment