The complex working lives of commuter and non-commuter students

This blog was kindly authored by Professor Adrian Wright, Martin Lowe, Dr Mark Wilding and Mary Lawler from the University of Lancashire, authors of Student Working Lives (HEPI report 195).

The cost‑of‑living crisis has reshaped the student experience, but its effects are not felt evenly. For example, commuter and non‑commuter students encounter these pressures differently. The Student Working Lives (HEPI Report 195) project highlights these contrasts, revealing different needs and constraints. We ask a practical question: How can universities support both groups?

The commuter paradox

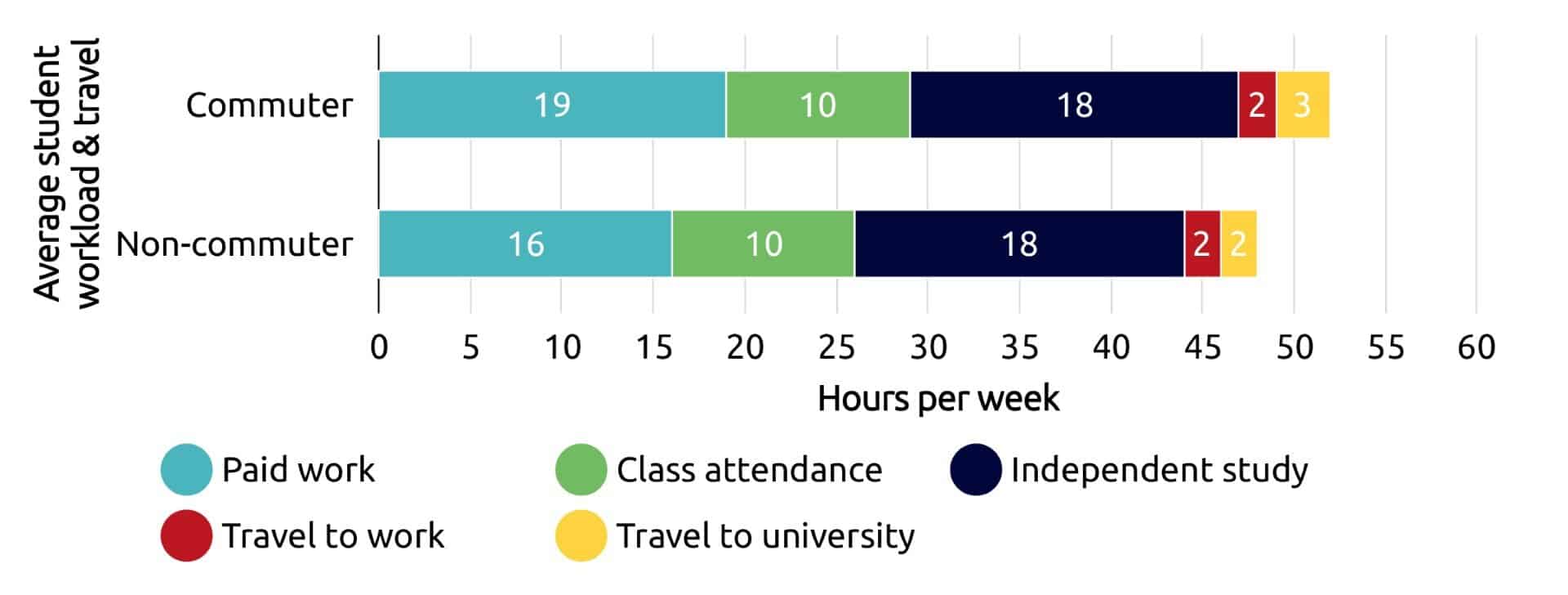

Commuter students face distinct time pressures, undertaking more paid work and travel per week on average and spending the same amount studying as their non-commuting counterparts.

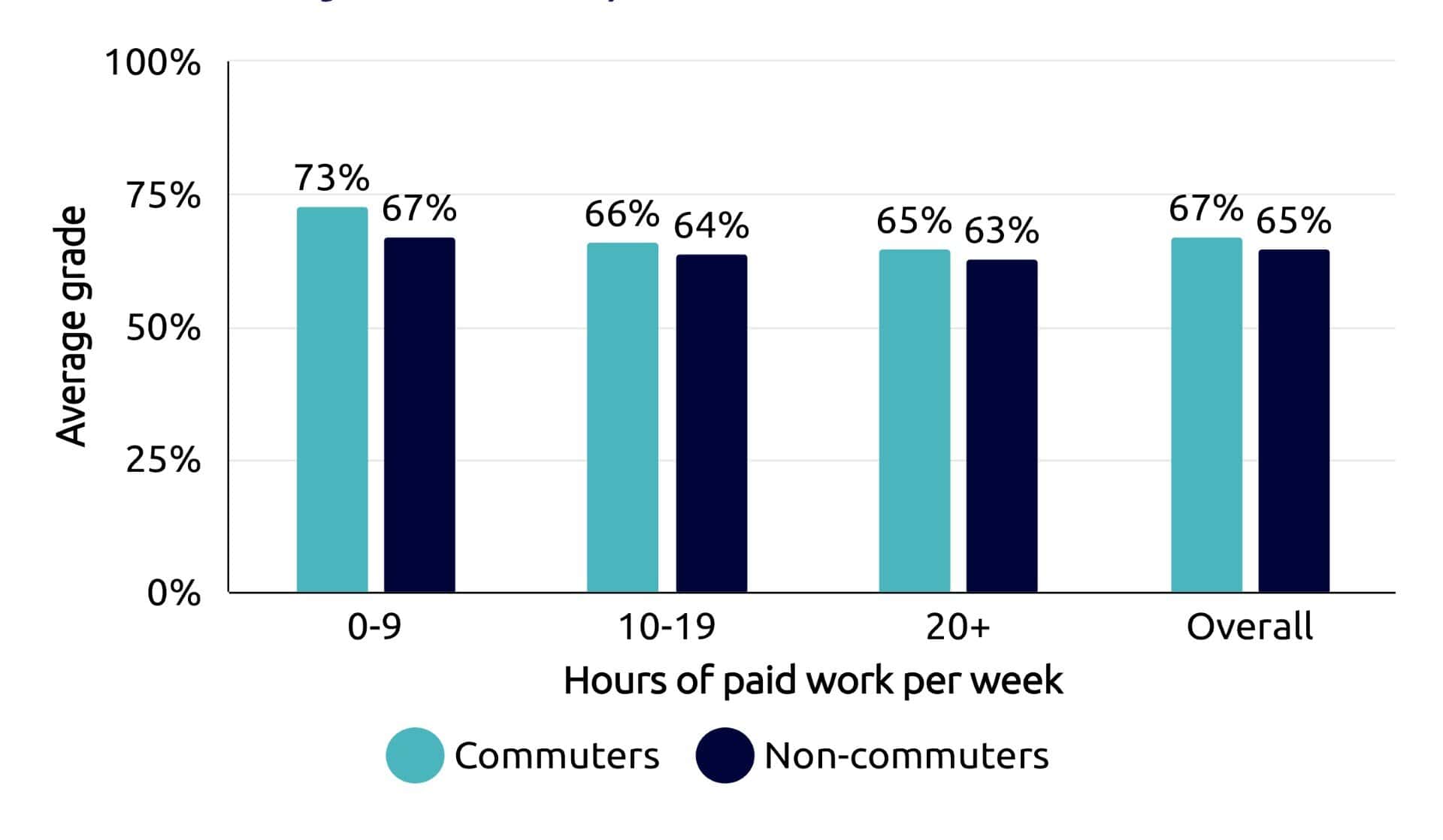

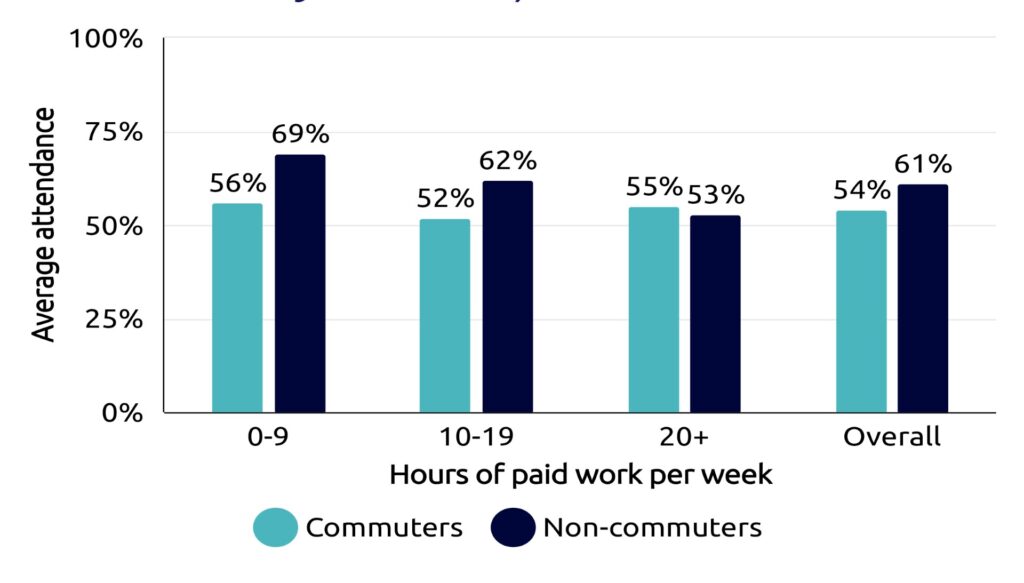

Table 3: Hours of paid work versus average attendance of commuter and non-commuter students

Despite attending fewer classes, commuters achieved stronger academic results, although for both groups, performance declined once working hours exceeded 10. This suggests that while commuters generally outperform their peers, both groups are susceptible to the effects of increased working hours.

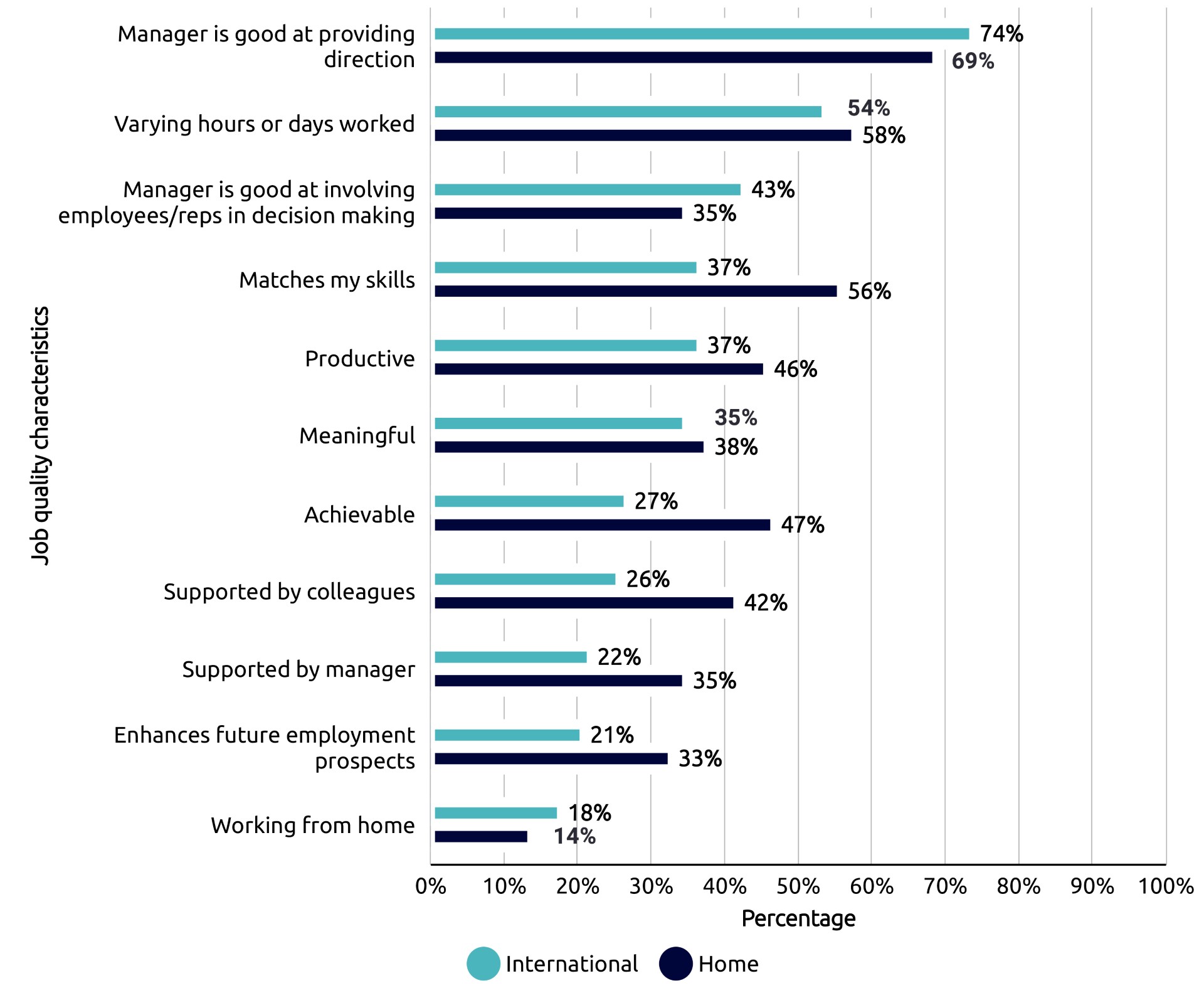

Our research shows that students in higher‑quality work were 20% more likely to achieve stronger academic results, highlighting work experience as a potential lever for improving academic success. We found non-commuters experience marginally tougher conditions. New data shows this extends to stress, anxiety or depression caused by or made worse by work (+5%) and under casual and zero-hour contracts (+4%), while commuters report better access to staff development (+12.2) and career guidance (+ 7.5).

Our data shows disadvantages for both groups, but neither is homogeneous. Background, proximity to campus, work, and institution, also shape their likelihood of success. This is not a simple categorisation; both groups need attention and support to address their specific needs.

Recommendations

- Condense and make timetables consistent

Uneven and variable timetabling increases travel costs and can threaten engagement. Universities should condense timetables and offer dedicated campus days to enable students to access support and social opportunities. Publishing schedules in advance helps all students, particularly those with existing work or caring responsibilities, organise regular shift patterns around their studies. Although often framed as a commuter issue, a focused timetable improves belonging for all students.

- Consider what matters for students in their context

While further categorisation of student groups may be useful in national policy making, the complexities of each group call for more understanding of what factors are most important in a student’s context, (including work, proximity to university, household type, mode of travel etc.)

- Reposition careers services to improve student employment

Universities should rebalance careers services and strengthen regional employer partnerships to expand access to meaningful and fair paid work. This would align student jobs with local skills needs that boost regional growth and graduate retention. Embedding support for workplace rights and expectations ensures all students can participate safely and confidently in the workforce during their studies, better preparing them for graduate roles in the future.

- Introduce curriculum interventions to utilise paid work experiences

Credit-bearing paid work interventions support students by aligning existing work commitments with graduate attributes while reducing the need for additional in‑class time, balancing overstretched workloads. By formally valuing paid work and guiding students to articulate these competencies, institutions can help all students use employment as a meaningful part of their university journey, strengthening employability and long‑term prospects.

Conclusion

The findings are nuanced, however, across all groups, one thing is certain: students need paid work. The sector’s role is to ensure that employment supports rather than hinders learning by easing financial and time pressures, improving job quality, and strengthening the connection between work and study.

Comments

James Fuller says:

This was a fascinating read and I have subsequently read the report that it is based on, which is excellent. Some hugely important questions and recommendations raised which are challenging (in a good way) and timely.

Reply

Jonathan Alltimes says:

I did not expect class attendance to be so low for some of the subjects shown in figure 12. Science subjects are missing. What is class attendance? Does it mean actually attended classes rather timetabled? Where is the lab, workshop or equivalent contact time traditionally led by PhD demonstrators and technicians?

Cross-tabulations of variables can be insightful, for example, regional differences.

Timetable recommendation seems to make sense, except there are no historically realistic worked examples, as with the other recommendations.

What about the provision of campus bus services? I am not advising free bus services although that may make perfect sense where campuses are not served by a local train station or not within/near a centre of population, as many universities provide shuttle bus services. Employees may benefit too. See the NUS 2023 Student Travel Survey Report.

Yes, the hours are excessive for all students, but that is a consequence of the maintenance grants and loans shrinking in real terms over 20 years. Not entirely sure if students studying for a profession (medic, pharma, vet) are supported by affluent parents or are higher paid and so need less paid work.

Reply

Add comment