Higher education policy: the lie of the land in England and Wales on the cusp of England’s post-16 white paper

- This speech was delivered by HEPI Director Nick Hillman at the University of Cardiff on Thursday, 16 October 2025.

Introduction

The other day, I was speaking to the University of Liverpool Council at the Ness Botanic Gardens on the Wirral, which as you know is four hours due north of here, pretty much on the Welsh / English border. I started my speech there by noting that I only exist because of the University of Liverpool, as my maternal grandparents met there in the early 1930s. Well, I also only exist because of the Welsh university system, as my parents met while they were students here in Wales in the early 1960s, just as my own children only exist because I met my wife in the early 1990s at university.

The fact that three generations of my family originally met while at university is a powerful reminder, at least to me, that higher education change lives. And at HEPI, we had another powerful reminder of that during our first event of this academic year, when – last month – we hosted the UK launch of the OECD’s Education at a Glance publication.

Education at a Glance

In case you have not come across it before, this is the most useful but worst titled publication on education that appears anywhere in the world each year. It is a vast 541-page compendium of comparative data that you need to pore over rather than glance at.

This year’s OECD report had a particular focus on tertiary education. While we have become used to people beating up on the UK higher education sector, the OECD actually painted a picture of a very successful sector playing to its strengths. When you look in from the outside, it seems the UK’s higher education institutions are not so bad after all.

For example, the OECD showed that, among the many developed countries covered in their report, the UK has:

- higher than average participation in higher education;

- lower than average graduate unemployment, irrespective of whether the individuals studied STEM, business or humanities; and

- among the very highest undergraduate completion rates anywhere in the world, vying with Ireland for the top spot.

I recognise the OECD is looking at averages for the UK as a whole and the position of Wales is not necessarily the same but, in general, the weaknesses the OECD found in were on the lack of good opportunities for people who do not succeed in education first time around.

Specifically, the OECD found a profound problem among young men, a rising proportion of whom are classified as NEETs (Not in Employment, Education or Training). While the OECD use historic data for a year or two past, last week’s brand new NEET data for Wales confirms the depressing picture. Indeed, it was even more salutary, noting:

The proportion of young people aged 16 to 24 in Wales who were not in employment, education or training (NEET) was 15.1% in the year ending June 2025, an increase of 3.6 percentage points over the year.

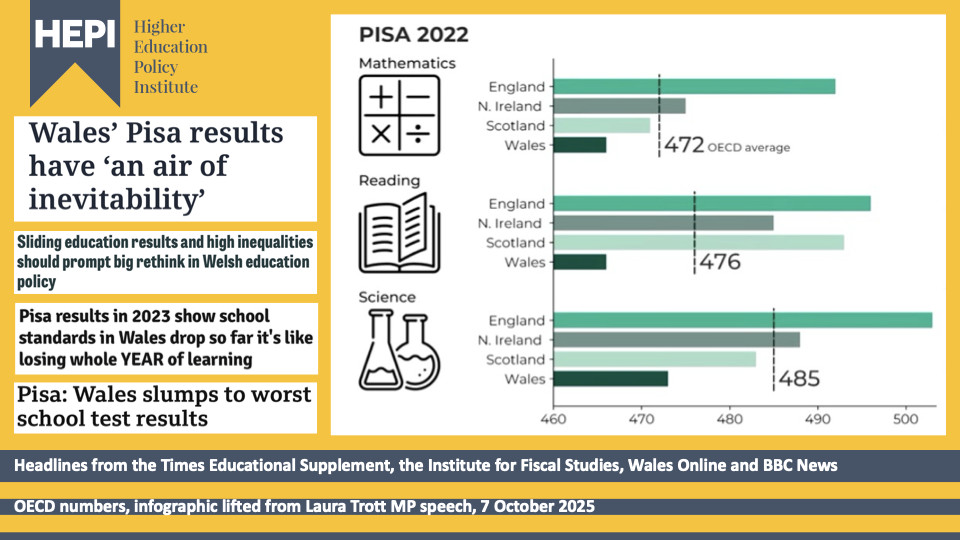

The OECD additionally found that the UK has the biggest gap of all developed countries when it comes to the difference in earnings between low-skilled adults and those who leave school with A-Levels (or equivalent). This should perhaps worry Wales even more than the rest of the UK, given that Wales scores the worst for schoolchildren’s academic performance for any part of the UK. Indeed, Wales is the only part of the UK to perform worse than the OECD average in all three areas of Mathematics, Reading and Science.

When it comes to funding of higher education, the OECD found the UK spends more than most other countries … but the shift to loan-based finance means direct government spending on each student in higher education is only half the OECD average and only half the amount spent ‘at primary to post-secondary non-tertiary levels’ ($13,000). Of course, the UK’s figures are distorted by England’s numbers because England is much larger than the other parts of the UK and has moved towards loans to a greater degree than Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. That is one reason why we have worked with London Economics and the Nuffield Foundation to look at the picture in each part of the UK separately.

There are three profound differences. First, the Exchequer cost is lowest in England, which also has the highest per-student income for institutions. Scotland is at the other end of the scale, with the largest Exchequer cost but the lowest unit-of-resource for institutions. Wales is, as you may expect, somewhere in the middle, with an Exchequer cost and a per-student income for institutions that lies between those in England and Scotland.

There is a similar picture when we look – secondly – at the balance of who is paying the costs of higher education. In England, it is mainly former students via the loan system; in Scotland, it is entirely taxpayers (and then some). In Wales there is a more even split approaching 50:50 between the Exchequer and graduates, arguably reflecting the public and private benefits of higher education more accurately. There are probably lessons from Wales for the rest of the UK here, though seemingly not for Kemi Badenoch, who complained at the Conservative Party Conference last week that higher education in England still costs taxpayers too much.

The third big difference is on student maintenance, where the system in Wales is more generous and more logical than those elsewhere in the UK. Each student gets more and the non-repayable grants are more generous in Wales than elsewhere – all undergraduates have at least a small grant whereas no one currently gets a grant in England, where grants were abolished in 2016. (Ministers promised the return of grants in England at the Labour Conference a fortnight ago, but only for some students on some courses, meaning it is likely to prove a mouse of an intervention and a very complicated one at that. It is certainly set to be nothing like the Welsh system.)

Many people I know are fans of the system in Wales for the way that it tries to strike a balance. However, while there are certainly far worse systems even within the rest of the UK, I personally think the benefits of the Welsh system are sometimes oversold. For example, I think the structure of student support in Wales is excessively generous to students who come from wealthy households. In other words, it is not means tested enough, perhaps explaining the need for the recent cuts to postgraduate support.

I have held this view consistently since the current Welsh funding system was introduced on the back of the Diamond review in 2018, but it has got me in trouble. After my concerns reached the front page of the Western Mail, I got not only an official rebuke from the Welsh Government but HEPI also received a formal complaint that came jointly from Universities Wales and NUS Wales. Rather than persuading me to change my view, I must admit this mainly had the effect of making me wonder if higher education debates in Wales are sometimes a little too cosy and stifled.

Boys, Boys, Boys

One other area where the OECD painted a less positive picture is on the differential educational performance of young men and young women. Women are more likely to obtain tertiary education across the developed world but the gap between men and women is bigger in the UK than elsewhere and has been growing while it has stayed the same on average across the OECD as a whole. According to the OECD:

In the United Kingdom, they [women] accounted for 56% of first-time entrants in 2023, up from 55% in 2013. Across the OECD, women make up 54% of new entrants on average, the same share as in 2013.

This is a convenient segue into some more of HEPI’s recent output because we have long worried about the educational performance of boys and young men and have published a number of papers on the topic over the years, with the most recent one appearing in March 2025. As Mary Curnock Cook wrote in the Foreword:

Something has surely gone wrong with education if boys – in aggregate at least – do worse than girls at all stages of education from early years to higher education and beyond.

Overall, out of every 100 female school leavers, 54 proceed to higher education by the age of 19; out of every 100 male school leavers, just 40 do so.

Again, the problems are worse in Wales than elsewhere. Over half of Inner London school leavers eligible for Free School Meals reach higher education by the age of 19; it is hard to get directly comparable figures for Wales but it seems the numbers are less than half as much for FSM Welsh-domiciled school leavers. Overall, while the gap in school leavers’ entry rates to higher education between men and women is dire in England, it is even worse in Wales. In fact, the proportion of young men who make it to higher education in Wales is lower than in every other part of the UK. It has been a known problem for at least 20 years yet for whatever reason, and perhaps because of misplaced fears of seeming politically incorrect, it has not been addressed.

Yet if male educational underachievement is not tackled, it seems certain that we will store up further societal problems for the future – including having more under-educated men veering towards the political extremes. Here, I note in passing the high polling of Reform for next year’s Senedd election. It is not rocket science to solve the boy problem, however, to take just one example, some schools following a ‘boy positive’ approach have managed to equalise their results for boys and girls and there is some great work underway in our own sector – for example, at Ulster University and the Arts University Bournemouth.

What remains completely absent, however, is any concerted interest at a national and ministerial level – certainly at Westminster and as far as I can tell in the Senedd too. People who did not want to take the Black Lives Matter protests seriously a few years ago sought to deflect attention from them by saying ‘All Lives Matter’, as if that was ever in doubt. Similarly, when Ministers wish to deflect attention from the crisis in boys’ education they like to respond by saying things like ‘Opportunity should be available to all’, which is true but it papers over the specific challenges faced by young men.

Our work on male underachievement sits alongside our work on the disadvantages faced by women, such as our reports on the substantial gender pay gap that remains in higher education as well as our other work on the overall gender pay gap among graduates. It also sits alongside a new HEPI report published just three months ago on the impact of menstruation on undergraduates’ attendance, academic engagement and wellbeing.

This revealed 70% of female students report being unable to concentrate on their studies or assessments due to period pain and that female students miss an average of 10 study days per academic year due to menstrual symptoms. It also suggested that just 15% of universities have a specific menstruation policy and, for those that do, the policy relates solely to staff rather than students.

So as I hope you can sense, the topics that tend to work best for HEPI are issues – like boys’ underperformance and the impact of menstruation on learning – that we should be speaking about more than we have done. Another area where that is true is public perceptions of higher education.

Misperceptions

A year ago, I had a drink with a neighbour who has a background in banking and two graduate children, meaning – in theory at least – that he knows the value of money and the value of education. However, when it came to universities, he expressed some typical rhetoric about them being too numerous, too big, too expensive and so on.

I responded by telling him I was on the Board at the University of Manchester and asking him to guess that institution’s financial turnover. His reply was £30 million – which is between 40 and 50 times smaller than the actual number of c.£1.3 billion (and over 20 times smaller than Cardiff’s turnover). Once my hangover had subsided, I contacted Bobby Duffy of the King’s College Policy Institute, who is the UK’s greatest expert on misperceptions – that is, the difference between what is true and what we tend to believe is true. This led over a process of many months to a new research project on what the public think about higher education, which we and King’s College launched the results of last month.

The findings are worth poring over in detail and we have brought hard copies of the work along for each you. Sone of the results particularly stand out.

For example, we gave people a list of seven institutions: Manchester City, Manchester United, the University of Manchester, the University of Oxford, the Daily Mail, MoneySupermarket.com and Greggs bakery.

When the public were asked about the relative financial size of these seven, the University of Oxford came fifth and the University of Manchester seventh, at the very bottom. More than half of respondents said they thought either Manchester City or Manchester United was the biggest in terms of their financial size; only 6% chose the right answer, the University of Oxford. The University of Manchester should be third in that list of seven by the way because, while it easily beats City and United in terms of its financial size, you might be surprised to know that Greggs has a turnover of £2 billion.

Similarly, when we gave the public a list of five big industries – legal services, accountancy services, aircraft manufacturing, telecommunications and higher education – and asked them to say which is least important in terms of export revenues, higher education was the most popular option. That result could not be any more wrong because higher education actually brings in much more export income than each of the others.

Let me share three other fascinating data points from the survey with you too:

- people greatly overestimate the level of graduate regret about going to higher education – on average, the public guess 40% of graduates would opt not to go to university if they had their again, when the actual proportion of graduates who say this is only 8%;

- on average, the public guess half (49%) of graduates say their university debt has negatively impacted their lives – in reality only 16% of graduates feel this way; and

- a majority of people, including a majority of Reform voters at the 2024 general election, have positive feelings about universities.

Oversight and regulation

Over the past decade, the oversight of tertiary education and research has been transformed in England, though not necessarily for the better. When I worked as a Special Adviser in Whitehall a dozen years ago, there was one Minister for Universities and Science who sat in one Government Department and who had oversight of one regulator that oversaw both teaching and research (known as the Higher Education Funding Council for England). But in recent years we have had different regulators, different Ministers and different Departments for the teaching and research functions of universities, meaning coordinated oversight has been missing.

Moreover, while the Westminster Government has promised more ‘clarity and coherence’, the latest Machinery of Government changes have made the current situation even more of a dog’s dinner. The Minister for Skills, who has responsibility for higher education, now has one foot in the Department for Education and another in the Department for Work and Pensions, which has just taken on the responsibility for ‘skills’, while the Minister for Science has one foot in the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology and another in the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Split ministerial posts tend to be a recipe for chaos, as I saw close up during my own time in Whitehall.

So while I know that the new Medr (the Commission for Tertiary Education and Research) here in Wales has had some teething challenges, on paper it makes a lot more sense than what England has. At one point, it was thought England’s long-awaited post-16 skills white paper was likely to be heavily influenced by Wales; given the latest reshuffle and associated changes, that now – perhaps regrettably – seems less likely.

International students

Finally, I want to end by touching on the issue of international students. The majority of the really big projects HEPI has undertaken over the past few years have focused on international students. Perhaps that is not surprising, given the OECD data I started with, which shows that, while there is one international student for every thirteen home students across the OECD as a whole, the ratio in the UK is completely different at 1:3.

That helps to explain why we have calculated (more than once) the net economic benefits of international students to the UK. The latest iteration found a gross benefit of £41.9 billion for just one incoming cohort of students and a net benefit (after taking account of the impact on public services and so on) of £37.4 billion. We split up this total to reveal a number for each one of the 650 parliamentary constituencies across the UK, including Cardiff South and Penarth, which is the top-performing constituency in Wales and one where international students contribute significantly over £300 million a year.

We have separately calculated the positive tax contributions of those former international students who stay in the UK to work after completing their studies, undertaken detailed studies on the Graduate Route visa and looked specifically at the experience of Chinese students in the UK. In addition, we produce each year a Soft-Power Index that looks at how many very senior world leaders have been educated to a higher level outside of their own home country. If they return home with fond memories of their time in the UK and a better understanding of our country, then this tends to bring real benefits. We will be launching the results for 2025 next week but last year’s Soft-Power Index, which is regularly quoted by Ministers, showed that, across the globe’s 195 countries, there were 58 serving world leaders who received some higher education in the UK, second only to the US.

I am going to stop here because I started the speech on a positive – on the way higher education changes lives for the better. And despite all the numerous political, financial and geopolitical challenges facing higher education across the UK, the continuing immense soft-power benefits delivered by UK higher education institutions is another area where there is a huge amount of which we can be proud.

Comments

Jonathan Alltimes says:

No one should doubt the economic and cultural value of UK higher education (and its contractors and their subcontractors). As someone who has consulted OECD statistics and reports for 30 years, direct comparisons with other countries using metrics needs to be interpreted with caution. With much respect to your dedication and influence on higher education policy, governments have been heading off course for 20 years in the direction of “knowledge economy”, whatever that is, led no doubt by the investment in information and communication technologies supporting other sectors of the economy, notably financial services (and all that interest in science and university spin outs, specifically the life sciences). (The University of Cambridge has a lot to answer.) A lot of people like tools and using their manual dexterity and physical abilities to make and control things and it is those sectors of the economy which lacked technical education and training since the 1980s, like manufacturing, construction, engineering, and infrastructure (and not the humanities, science, and computing: the knowledge economy). We need lots technical graduates and apprenticeships, preferably those who are both. One thing which is a problem is the contribution of higher education to improving the rate of economic growth, given its economic size, faculty development, and massive state investment in the form of student loans and grants, it has had 25 years to deliver the goods and it has not. The muddle over ministerial responsibilities reflects the ability to enact political control and that is a consequence of political confusion about the purpose and function of the university and the bureaucratic confusion enacted through the QAA and then the OfS. Ministers should stop trying to use the universities to deliver their social and economic ambitions that are best delivered through the business sector.

Reply

Add comment