A postmortem of M&A activity to date

Join HEPI and Huron for a webinar 1pm-2pm Tuesday 10 February examining how mergers, acquisitions and shared services can support financial sustainability in higher education. Bringing together a panel of speakers, the session will explore different merger models, lessons from the US and schools sectors, and the leadership and planning required to make collaboration work in practice. Discover our speakers and sign up now.

This blog was kindly authored by John Workman, Susie Hills, and Shaun Horan, Huron. Huron is a HEPI Partner.

The September 2025 announcement of Kent and Greenwich’s intended merger into the tentatively named London and South East University Group (LSEUG) reignited merger and acquisition (M&A) chatter across the sector. Consolidation in UK higher education has been mostly rare to this point, for a host of regulatory, cultural, and governance reasons. But might this be a turning point?

The UK sector is hardly alone. Another high-profile merger has been the talk of the Australian sector since 2024, when the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia announced they would merge into Adelaide University. This new institution will boast approximately 70,000 students when officially joined up in 2026.

The United States has also experienced an unprecedented volume of M&A activity this decade. Since 2020, approximately 100 universities have closed or merged into other institutions, accounting for nearly 200,000 students and more than 2 billion USD in endowment assets. Huron Consulting Group’s analysis of 10 years of financial and enrollment data indicates that, within the next decade, another 370 institutions, representing 600,000 students, will experience financial pressures similar to those since-closed and merged institutions.

Is there more to come?

One school of thought argues that consolidation is simply a numbers game. The US has roughly 7.8 universities for every 1 million in population, significantly more than the 3.8 universities per 1 million people in Canada, or the 2.4 in the UK. While an exact tipping point or golden ratio isn’t obvious, the numbers seem to imply the US has more opportunity for consolidation than its northern or transatlantic peers. Not necessarily a surprise, given that sector’s greater number of small institutions. But it’s all relative. When compared to the 1.6 universities per 1 million people of both Australia and New Zealand, it is the UK that appears ripe for downsizing.

Of course, there are also important nuances about how and why each sector evolved, and the pressures they face today. US consolidation is partially the result of declining youth populations and shrinking enrolments, especially among the small institutions most dependent on tuition revenue. Pressure in the UK and Australia is driven more by policy changes and volatile international student numbers.

Importantly, there are also shared pressures driving M&A conversations across sectors. In each anglosphere country, university revenue has failed to keep pace with rising costs (or even inflation) for over a decade. Our marketised, tuition-driven models are exposed to evolving student preferences and alternative providers. And each sector faces waning public support.

7 executive lessons from past M&A activity

Given commonalities in our operating challenges and environment, it’s appropriate to heed any and all lessons from anglosphere M&A activity so far. Even financially healthy institutions should at least consider strategic options in this changing landscape.

Below are some of the most important lessons from these engagements that all HE leaders should consider, drawn from our M&A work with over 30 institutions.

1) Consolidation alone is not the endgame.

Mergers shouldn’t be pursued as a quick fix but rather in service to a specific strategy focused on mission and sustainable financial health. A successful partnership rarely results from two struggling institutions joining up. More often, this merely creates one larger institution, now facing both sets of legacy challenges. One university executive described this approach as ‘pitching two anchors together and hoping they swim’. Instead, the best-case scenario is to combine two institutions with complementary strengths. Leaders of institutions with strong financial resources may pursue strategic ventures to advance their mission, expand academic offerings, or enable growth. On the flip side, leaders of financially challenged institutions should identify existing strengths, or potential areas of investment, that bring value into an alliance.

2) No one-size-fits-all model, but different approaches are not created equal, either.

There is a wide spectrum of potential strategic alliance types, including third-party agreements, joint ventures, real estate divestments, and full mergers. Importantly, these models have varying degrees of transformational impact to the institutions involved. Some leadership teams have gravitated to what they perceive as the ‘maximum necessary’ level of transformation. Cross-campus shared services, for example, is often touted as a more tenable solution that allows institutions to retain their independent missions, identities, and portfolios. Yet, these partnerships have, in practice, led to almost equal levels of complexity and disruption as consolidation, with much less financial benefit than anticipated.

3) An underdeveloped partnership strategy is the most common failure path.

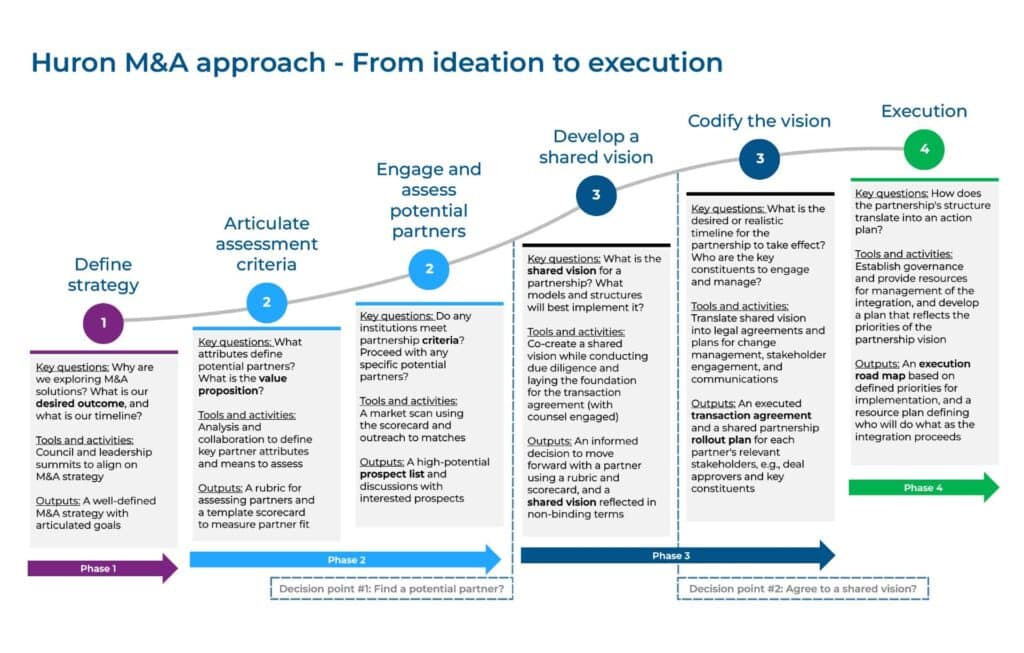

Too many leadership teams have discounted or attempted to rush the critical first steps on strategy and goal setting, opting to dive right into negotiation of business terms. The framework below outlines all the steps we have found are necessary for a successful merger, including strategic setting. Individual institutions that do not clearly define specific aims for strategic partnerships will waste energy and resources engaging poor-fit partners that should be spent on better, limited opportunities. Or worse, two institutions deep into consolidation conversations may find they are not fully aligned on culture, governance, or mission. One critical – and often fraught – decision is how to describe a consolidation. The chief executive of one university near the end of a deal reflected that, while the arrangement had a clear acquirer and acquiree, they had carefully avoided that language. Unfortunately, this created later tension and misunderstanding. She commented they had ‘tap danced around the obvious dynamics, and it would have been better if we had all been honest at the outset.’ A senior leader at a different institution noted: ‘There are no mergers in higher education, only acquisitions. But that sounds too corporate. So, we all say M&A just to be polite.’

4) The more challenging the financial situation, the faster leaders must act.

One of the most common and costly mistakes is not using time effectively – either spending too much on the wrong opportunity or leaving too little to pursue the right one. Frequently, institutions in need of a strategic alliance wait until circumstances become dire to start exploring options. This weakens their position by reducing time to find a compatible partner that fits their unique needs. In the worst cases, institutions with financial challenges couldn’t stay solvent long enough to execute a partnership and had to close. In other cases, institutions fail to appreciate the runway required to bring along key constituents and ultimately succumb to resistance that could have been overcome with earlier action.

5) Unhelpful increase in M&A ‘window shopping’ distracts and wastes valuable time.

Growing interest in M&A across the industry has spurred phantom activityby encouraging hopefuls, regional expanders, and serial acquirers to ‘window shop’ with limited commitment. For every successful merger or acquisition, there is a 10x increase in unhelpful phantom activity, which is a poor use of time, money, and energy for any leadership team, especially those of already-struggling institutions in need of partnership.

6) Both offensive and defensive stances are prudent in a fast-changing market.

A handful of leading, financially healthy institutions have pursued aggressive M&A strategies, viewing inorganic growth as their best financial path forward. Both Northeastern and Villanova have generated hundreds of millions in net-new revenue and assets through a handful of strategic acquisitions. Leadership teams taking a more defensive stance have also acted in the best interest of their institutions. For example, several universities have absorbed small, local campuses. While these acquisitions don’t always appear strategic when viewed in isolation, they successfully prevented competitors from creating a foothold in the acquirer’s backyard.

7) M&A centered on the expansion of academic offerings has the highest success rate.

While somewhat subjective, evaluating trends in the success and failure of M&A instances tells an interesting story. One way to categorise partnerships is by their stated goal. This includes geographic expansion, real estate acquisition, achieving scale or efficiency, and adding academic offerings to enhance the portfolio. While a handful of institutions have succeeded in using M&A to expand geographically, partnerships based on expanding academic offerings have the highest success rate, by a wide margin. For example, Texas Christian University (TCU) and the University of North Texas Health Science Center successfully created a private-public partnership to establish a new school of medicine. Arizona State University acquired Thunderbird School of Management as a means to quickly add an MBA offering to their portfolio. This ‘build vs buy’ dynamic is common in the corporate world but new to higher education, where a marketplace of assets is only now beginning to form. Several universities have found that the ‘buy’ option is a faster and cheaper way to grow student numbers and revenue. Conversely, other M&A approaches have not fared as well. One senior leader reflected on a recent acquisition: ‘We thought we were acquiring a unique physical asset in a new location – what we actually got was a large deferred maintenance backlog’.

What next?

Institutions that learn how to navigate this evolving marketplace will play a pivotal role in shaping higher education’s next decade, while bolstering their own institutional resilience.

Want to find out more about this topic? Join HEPI and Huron for a webinar 1pm-2pm Tuesday 10 February . Discover our speakers and sign up now.

Huron’s dedicated M&A team would be happy to discuss strategy, next steps, and mistakes to avoid with any leadership team considering their options. Contact us here.

Comments

Add comment