WEEKEND READING: On legal education: is AI churning out super or surface-level lawyers?

Join HEPI for a webinar on Thursday 11 December 2025 from 10am to 11am to discuss how universities can strengthen the student voice in governance to mark the launch of our upcoming report, Rethinking the Student Voice. Sign up now to hear our speakers explore the key questions.

This blog was kindly authored by Utkarsh Leo, Lecturer in Law, University of Lancashire (@UtkarshLeo)

UK law students are increasingly relying on AI for learning and completing assessments. Is this reliance enhancing legal competence or eroding it? If it is the latter, what can be done to ensure graduates remain competent?

Studying law equips students with key transferable skills – such as evidence-based research, problem solving, critical thinking and effective communication. Traditionally, students cultivate doctrinal (and procedural) knowledge by attending lectures, workshops and going through assigned academic readings. Thereafter, they learn how to apply legal principles to varying facts through assessments and extracurriculars like moot courts and client advocacy. In this process, they learn how to construct persuasive arguments and articulate ideas, both orally and in writing. However, with widely available and accessible Gen AI, students are taking shortcuts in this learning process.

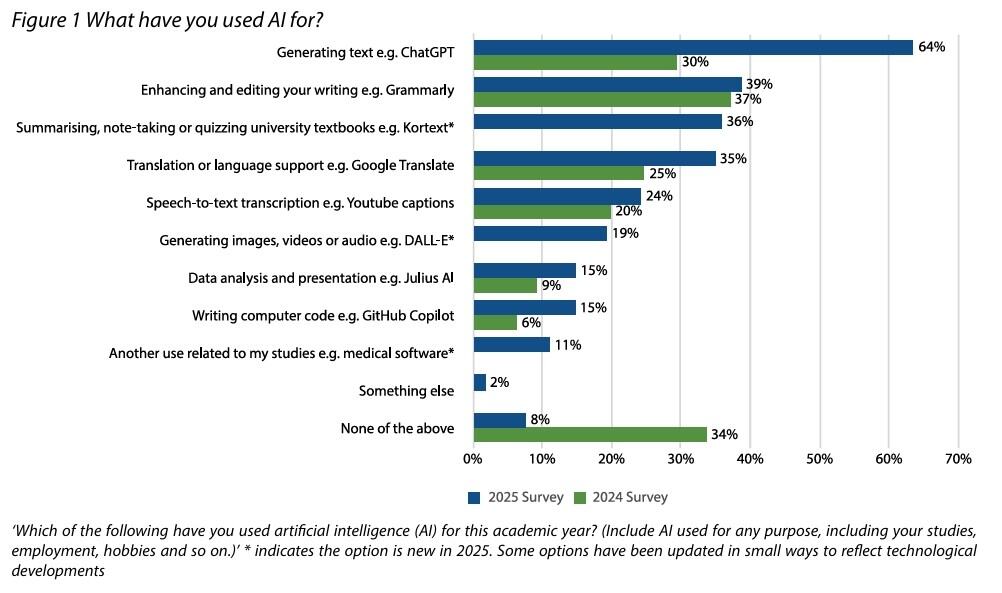

The HEPI/Kortext Student Generative AI Survey 2025 looked into AI use by students from a range of subjects. It paints a grim picture: 58% of students are using AI to explain concepts and 48% are using it to summarise articles. More importantly, 88% are using it for assessment related purposes – a 66% increase compared to 2024.

Student Generative AI Survey 2025, Higher Education Policy Institute

Rooted in inequality

Students are relying on shortcuts largely due to rising economic inequality. Survey data published by the National Union of Students shows 62% of full-time students work part-time to survive. This translates into reduced studying time, limited participation in class discussions and extracurriculars. Understandably, such students may find academic readings (which are often complex and voluminous) as a chore, further reducing motivation and engagement. In this context, AI offers a quick fix!

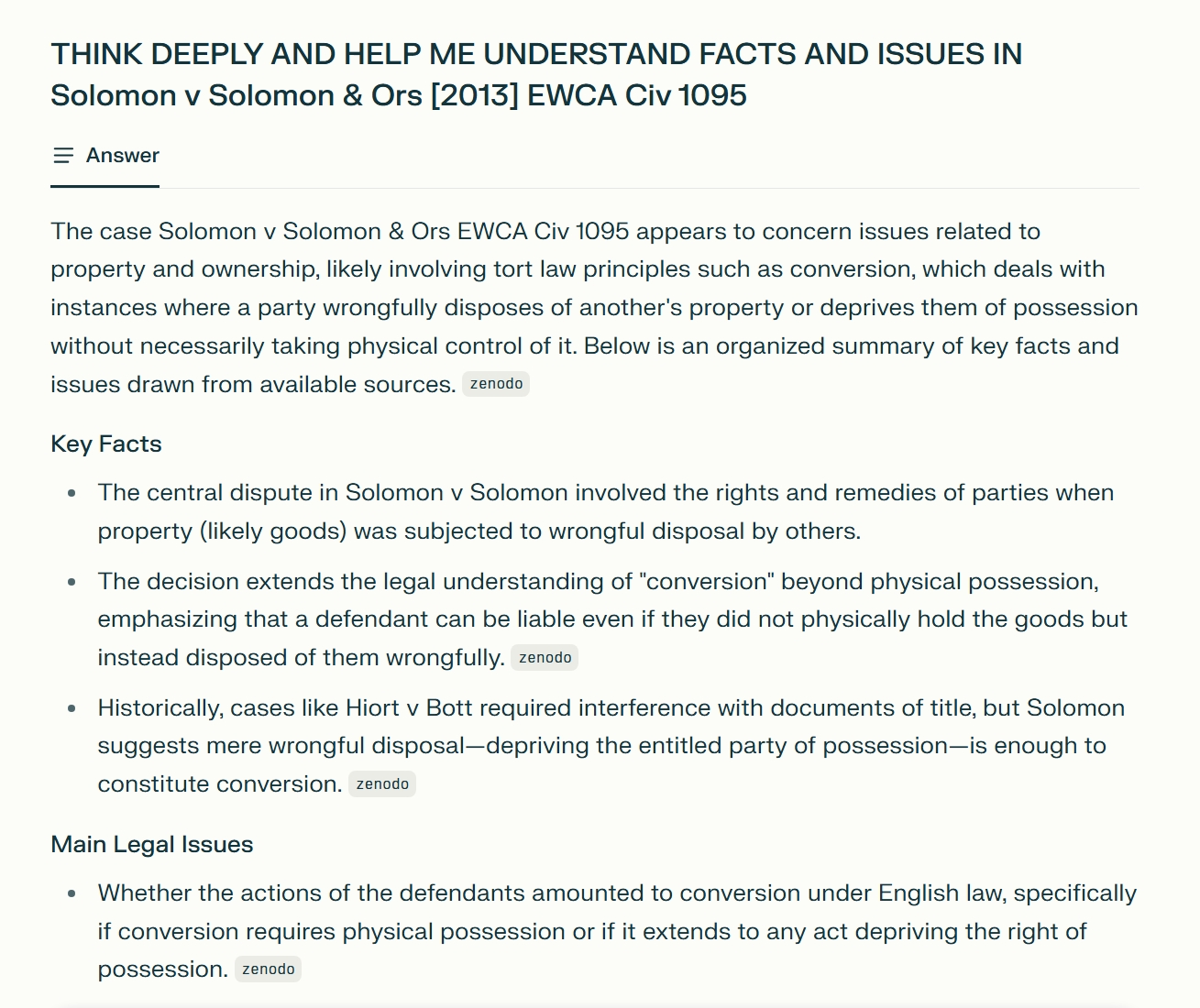

Prompt and output generated by perplexity.ai on 7 November 2025 showing AI-produced case summaries.

The problem with shortcuts

Quick fixes, as shown above, promote overreliance: resulting in cognitive replacement. Most LLB first-year programmes aim to cultivate critical legal thinking: from the ability to apply the law and solve problems in a legal context to interpreting legislative intent to reading/finding case law and developing the skills to spot issues, weigh precedents and constructing legal arguments. Research from neuroscience shows that such essential skills are acquired through repeated effort and practice. Permitting AI usage for learning purposes at this formative stage (when students learn basic law modules) inhibits their ability to think through legal problems independently – especially in the background of the student cost-of-living crisis.

More importantly, only 9 out of more than 100 universities require law degree applicants to sit the national admission test for law (LNAT) – which assesses reasoning and analytical abilities. This variability means we cannot assume that all non-LNAT takers possess the cognitive tools necessary for legal thinking. This uncertainty reinforces the need to disallow AI use in first-year law programmes to ensure students either gain or hone the necessary skills to do well in law school.

Technical discussion

Furthermore, from a technical perspective, the shortcomings of AI summaries are well known. AI models often merge various viewpoints to create a seemingly coherent answer. Therefore, a student relying on AI to generate case summaries enhances the likelihood of detaching them from judicial reasoning (for example, the various structural/substantive principles of interpretation employed by judges). It risks producing ill-equipped lawyers who may erode the integrity of legal processes (a similar argument applies to statutes).

Alongside this, AI systems are unreliable: from generating fake case-law citations to suggesting ‘users to add glue to make cheese stick to pizza.’ Large language models (LLMs) use statistical calculation to predict the next word in a sequence – therefore, they end up hallucinating. Despite retrieval-augmented generation – a technique for enhancing accuracy by enabling LLMs to check web sources – the output generated can be incorrect if there is conflicting information. Furthermore, without thoughtful use, there is an additional concern that AI sycophancy will further validate existing biases. Hence, despite the AI frenzy, first year students will be better off if they prioritise learning through traditional primary and secondary sources.

How to ensure this?

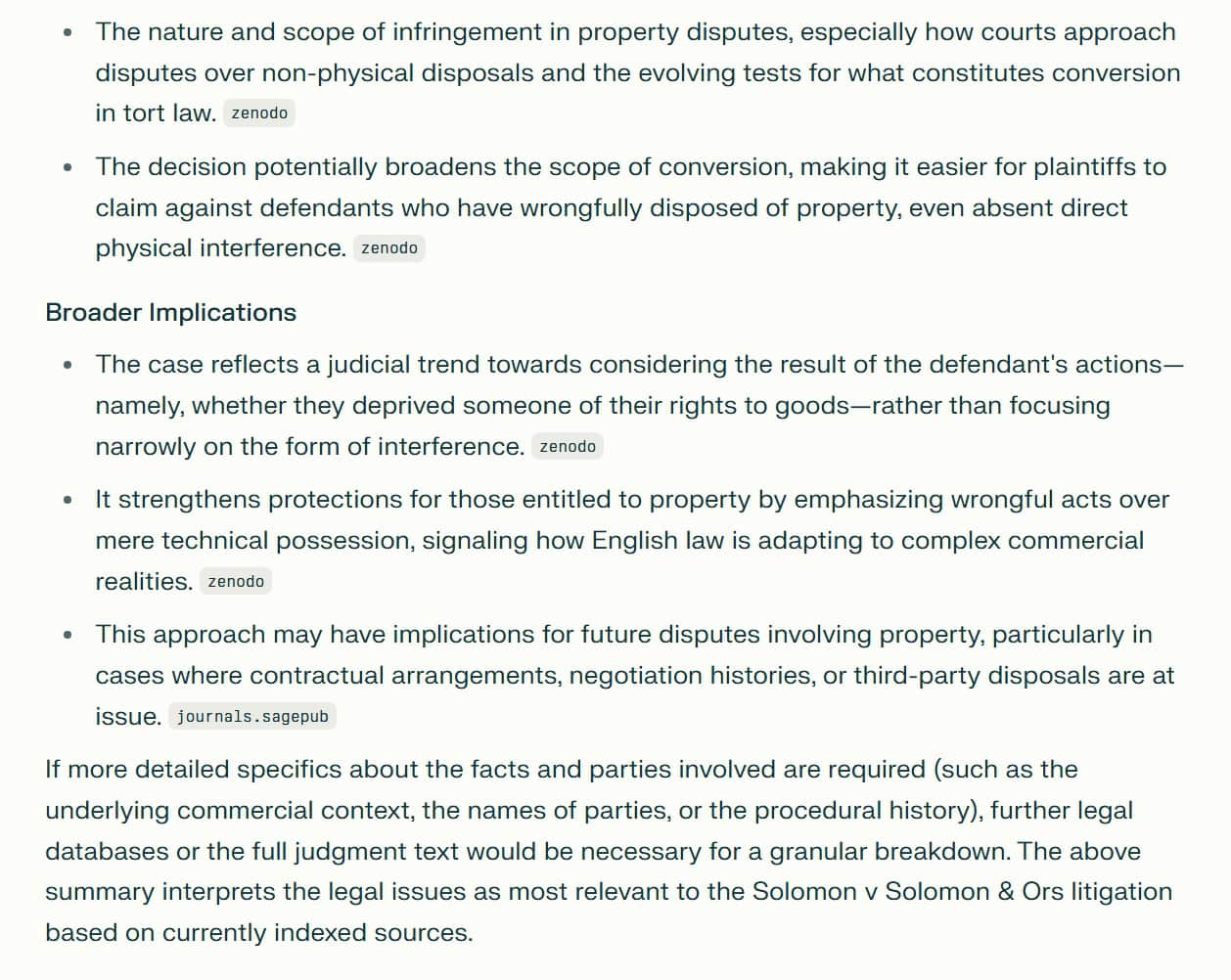

Certainly, we cannot prohibit student’s from using AI in a private setting; but we can mitigate the problem of overreliance by designing authentic assessments evaluated exclusively through in-person exams/presentations. This is more likely to encourage deeper engagement with the module. Now more than ever, this is critical. Despite rising concerns of AI misuse and the inaccuracy of AI text detection primarily due to text perplexity (high false positives; especially for students for whom English is not their first language), core law modules (like contract law and criminal law) continue to be assessed through coursework (for either 50% or more of the total module mark).

However, sole reliance on in-person exams will not suffice! To promote deeper module engagement (and decent course pass rates), the volume of assessments will need to be reduced. As students are likely to continue working to support themselves, universities could benefit from the support and cooperation of professional bodies and the Office for Students. In fact, in 2023, the Quality Assurance Agency highlighted that universities must explore innovative ways of reducing the volume of assessments, by ‘developing a range of authentic assessments in which students are asked to use and apply their knowledge and competencies in real-life’.

To promote experiential learning, one potential solution could be to offer assessment exemption based on moot-court participation. Variables such as moot profile (whether national/international), quality of memorial submitted, ex-post brief presentation on core arguments, and student preparation could be factored to offer grades. Admittedly, not all students will pursue this option; however, those who choose to participate will be incentivised.

Similarly, summer internships or law clinic experiences can be evaluated through patchwork assessment where students can complete formative patches of work on client interviews, case summaries and letters before action, followed by a reflective stitching piece highlighting real world learning and growth.

Delayed use of gen AI – year II and onwards

It is crucial to emphasise that despite the critique of Gen AI, its vast potential to enhance productivity cannot be overlooked. Nevertheless, what merits attention is that such productivity is contingent on thoughtful engagement and basic domain specific knowledge – which is less likely to be found in first year law students.

Thus, a better approach is to delay approved use of AI until the second year of law. To ensure graduates are job ready, modules such as Alternative Dispute Resolution and Professional Skills could go beyond prompting techniques to include meaningful engagement with technology: through domain specific AI tools, contract review platforms and data-driven legal analytics ‘to support legal strategy, case assessment, and outcomes’.

Communication skills remain key

Above all, despite advances in tech, law will remain a people-centred profession requiring effective communication skills. Therefore, in the current climate, law school education should emphasise oral communication skills. Prima facie, this approach may seem disadvantageous to students with special needs, but it can still work with targeted adjustments.

In sum, universities have a moral responsibility to churn out competent law graduates. Therefore, they must realistically review the abilities of AI to ensure the credibility of degrees and avoid mass-producing surface-level lawyers.

Acknowledgement: I am grateful to Rachel Nir, Director of EDI at the School of Law and Policing, University of Lancashire, for her insightful comments and for kindly granting the time allowance that made this research possible.

Comments

Ronald Barnett says:

A cautionary tale but it does not go far enough. There are already appearing instances of expert witnesses producing their testimony on the basis of AI; and of barristers themselves relying over-heavily on AI to prepare their cases. The forensic attention to words, to the crafting of texts – oral and written – is being lost in the legal profession. Texts are being fabricated in the worst sense of that term. The legal mind, in turn, is depleted.

This set of impacts on what we take ‘law’ to be – the careful scrutiny of texts and ensuing scrupulous judgement – is doubtless being mirrored in most other professions, including the medical profession. The errors, the biases, the vacuousness is one set of things; the loss of mind in a sphere that is supposed to hold other estates of society to account is quite another.

Ron Barnett

Reply

Charlize Anne says:

Your technical understanding is sound, and it’s a really interesting take. I do wonder, though, how realistic its implementation would be. Would universities genuinely be willing to adopt this approach when so many are keen to showcase how tech-focused their law courses are?

Reply

Jonathan Alltimes says:

How can LLMs save time if not error free?

Reply

Add comment