A Christmas present or a nightmare before Christmas? Assessing the Curriculum and Assessment Review

- HEPI Director, Nick Hillman, takes a first look at today’s Final Report from the Curriculum and Assessment Review.

It feels like Christmas has come early for policy nerds. At 6.01am this morning, we finally got sight of Building a world-class curriculum for all, the long-awaited report from the Government’s independent Curriculum and Assessment Review (CAR).

Overseen by Professor Becky Francis, who is an experienced educational leader and researcher and someone who also has a background in policy, it was commissioned when the Labour Government was facing brighter days back in their first flush.

The first thing to note about the report is that, in truth, independent reports commissioned by governments are only half independent. For example, the lead reviewer is usually keen to ensure their report lands on fertile soil (and, indeed, is usually chosen because they have some affinity to the people in charge). In addition, independent reviews are supported by established civil servants inside the machine and there is usually a conversation behind the scenes between the independent review team and those closest to ministers as the work progresses. (In higher education, for example, both the Browne and Augar reviews fit this model.) So it is no great surprise that the Government has accepted most of what Becky’s largely evidence-led team has said.

Yet anyone reading the press coverage of the CAR while it has been underway, or anyone who has seen the front page of today’s Daily Mail, which screams ‘LABOUR DUMBS DOWN SCHOOLS’, may wonder if the report that has landed today is the nightmare before Christmas rather than a welcome festive present. There is lots to like but the document also feels incomplete, especially – for example – for people with an interest in higher education. So it is perhaps best thought of as a present for which the batteries have yet to arrive.

Nonetheless, this morning I spoke at the always excellent University Admissions Conference hosted annually by the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference (HMC) and the Girls’ School Association (GSA) and I could not help wondering aloud whether any new restraints on state-maintained schools might give our leading independent schools, who are much freer to teach what they like, an additional edge – especially as academy schools are already, even before today, having freedoms ripped from them.

What does the CAR say (and what does it not say)

But what does the review, which had a team of 11 beneath Becky (including one Vice-Chancellor in Professor Nic Beech and also Jo-Anne Baird from the Oxford University Centre for Educational Assessment) actually say?

The first thing to note is that it is much better than the Interim Report, which said little, sought to be all things to all people and read like it had been written by one of the better generative AI tools.

In terms of hard proposals, the Final Report starts and ends with older pupils, those aged 16 to 19, for whom we are told there should be ’a new third pathway at level 3 to sit alongside A-Levels and T Levels.’ If this feels familiar, it is because the Curriculum and Assessment Review’s emerging findings helped shape the recent Post-16 Education and Skills white paper and, more importantly, because there is already such a pathway populated by qualifications like BTECs.

So there is a sense of reinventing the wheel here, with (to mix my metaphors) politicians putting a new coat of paint on the current system. In many respects, the material on 16-to-19 pupils is the least interesting part of the report – especially as there is next to nothing at all on A-Levels. The review team starkly states, ‘we heard very little concern regarding A Levels in our Call for Evidence and our sector engagement’, so they basically ignore them – in a world of change, A Levels continue to sail steadfastly on.

As trailed in the newspapers, there is a recommendation for new ‘diagnostic Maths and English tests to be taken in Year 8.’ This would obviously help track progress between the tests taken at the end of primary school (in Year 6) and the public exams taken at age 16. But the idea has already prompted anger from trade unionists, almost guaranteeing that the benefits and downsides will be overegged in the inevitable political rows to come.

There are also numerous scattergun subject-by-subject recommendations. These are largely sensible (see, for example, the iideas on improving English GCSEs or the section on Science) but also a little unsatisfying. Some of the subject-specific changes are a little trite or inconsequential (like tweaks to the name of individual GCSEs) while others need much more detail than a general review of everything that happens between the ages of 11 and 19 is able to offer. Any material changes will need to be at a wholly different level of detail to what we have got today, and they will be some years away, so may make no difference to anyone already at secondary school.

Other points to note include that the Review is Gove-ian in its love of exams, which it stresses are a protection against the negatives of AI, over coursework. (I suspect Dennis Sherwood, the campaigner against grading inaccuracy will be incandescent about how the report appears to skate over some of the imperfections of how exams currently operate.) However, despite the support for exams, one of the crunchiest recommendations in the review is the proposal of a 10% reduction in ‘overall GCSE exam volume’, which we are told can happen without any significant downsides, though the tricky details are palmed off to Ofqual and others.

The English Baccalaureate and Progress 8

The one really clear place where Professor Francis’s review team and the Government, who have generally accepted the recommendations, are out of kilter with one another is on Progress 8.

Progress 8 is a school accountability measure that assesses how much ‘value-added’ progress occurs between primary school (SATs) and GCSEs. It is such a favoured measure that the Government has recently proposed a new Progress 8 measure for universities (which is a mad idea that wrongly assumes universities are just big schools – in reality, it is a defining feature of universities that they set their own curricula and are their own awarding body).

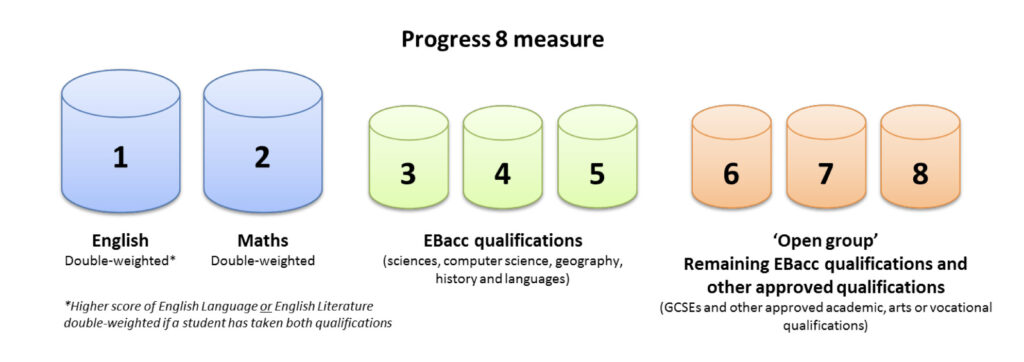

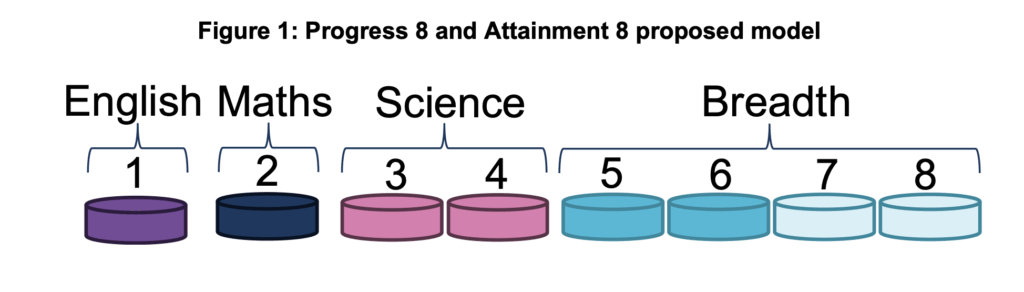

Becky Francis opposes the EBacc, which is a metric related to, but separate, from Progress 8, yet she wishes to maintain some vestiges of the EBacc within Progress 8. While the EBacc focuses specifically on how many students achieve qualifications in a list of specially favoured subject areas (English Lang and Lit, Maths, Sciences, Geography or History plus a language), the CAR recommends ‘the removal of the EBacc measures but the retention of the EBacc “bucket” in Progress 8 under the new title of “Academic Breadth”.’

This is something the Government is not running with, favouring less restrictions on Progress 8 instead, which may or may not reinvigorate some creative subjects. Yes, it is all exceptionally complicated but Schools Week have an excellent guide and the two pictures below (from Government sources) might help: the first shows the status quo on Progress 8 and is what Becky Francis wishes to maintain (though pillars 3, 4 and 5 would be renamed if she got her way); the second shows the Government’s proposal.

How does it fare?

Call me simple, but I was always going to judge the Curriculum and Assessment Review partly on the extent to which it tackled specific challenges that we have looked at closely at HEPI In recent years. Here the CAR is a mixed bag. On the positive side of the ledger, the review recommends more financial education, reflecting the polling we conducted to help inform the CAR’s work: when we asked undergraduates how well prepared they felt for higher education, 59% said they felt they should have had more education on finances and budgeting.

The most obvious problem that the CAR insufficiently addresses is the huge underperformance of boys. This issue usually gets a namecheck in Bridget Phillipson’s interviews but it was entirely ignored in the recent Post-16 white paper; in the CAR, it does at least receive a quick nod and just maybe some of the proposed curriculum changes will benefit boys more than girls. But there is more focus on class and other personal characteristics than sex and in the end the brief acknowledgement of boys’ underperformance does not lead to anything properly focused on the problem.

This is very strange for we simply cannot fix the inequalities in outcomes until we give the gaps in the attainment of boys and girls the attention they deserve. I am beginning to think I was wrong to be so hopeful that a female Secretary of State was more likely to focus on this issue than a male one (on the grounds that it would be less sensitive politically).

Another area where we at HEPI have been mildly obsessed is the catastrophic decline in language learning, as tracked for us by the Oxonian Megan Bowler. Here, as with boys, the new review is disappointing. In the section looking at welcome subject-by-subject changes, the recommendations on languages are both relatively tentative and relatively weak. As one linguist emailed me first thing this morning, ‘It is pretty remarkable that the CAR’s decision on languages runs exactly contrary to the best and consistent advice of the key language advisers on the issue’. However, the Government’s response goes a little further and Ministers promise to ‘explore the feasibility of developing a new qualification for languages that enables all pupils to have their achievements acknowledged when they are ready rather than at fixed points.’ We might not want languages always to be treated so differently from other subjects but I am still chalking that up as a win.

The CAR also ignores entirely one issue that is currently filling some MPs’ postbags – the defunding of the International Baccalaureate (IB). The IB delivers a broad curriculum for sixth-formers, is liked by highly selective universities and tackles the early specialisation which marks out our education system from those in many competitor nations. Back in the heady Blair years, Labour politicians loved the qualification and promised to bring it within touching distance of most young people.

As HEPI is a higher education body, it also feels incumbent upon me to point out that higher education is largely notable by its absence in the CAR, with universities being mentioned just nine times across the (almost) 200 pages and despite schools and colleges obviously being the main pipeline for new students. It is rather different from the days when universities were regarded as having a key direct role to play in designing what goes on in schools. Indeed, our exam boards tended to originate within universities.

The odd references to universities that do make it in to the CAR report are not especially illuminating. For example, more selective universities appear as part of the rationale for killing the EBacc: ‘the evidence does not suggest that taking the EBacc combination of subjects increases the likelihood that students attend Russell Group universities.’ Universities also appear in the section on bolstering T Levels, with the review proposing ‘The Government should continue to promote awareness and understanding of T Levels to the HE sector.’ But that is about it.

Incidentally, there is also less in the report on extracurricular activities than the pre-publication press coverage might have led you to believe, even if the Government’s response to the review does focus on improving the offer here.

Trade-offs

Becky Francis used to head up the UCL Institute of Education (IoE), which is an institution that has always wrestled with excellence versus opportunity. Years ago, I sat in a learnèd IoE seminar on why university league tables are supposedly pernicious – but I had to walk past multiple banners boasting that the IoE was ‘Number 1’ in the world for studying education to get to the seminar and, while I was in the room, news came through that the IoE was going to cement its reputation and position by merging with UCL.

Such tension is a reminder that educational changes generally have trade-offs and the Executive Summary of the main CAR document admits: ‘All potential reforms to curriculum and assessment come with trade-offs’. Abolishing the EBacc as the CAR team want and watering down Progress 8 as the Department for Education want, might help some pupils and some disciplines while making the numbers we produce about ourselves look better – though the numbers produced by others about us (at places like the OECD) could come to tell a different story in time.

In the end, we have to recognise that there are only so many hours in the school day, only so many (ie not enough) teachers and only so much room in pupils’ lives, not to mention huge diversity among pupils, schools and staff, which together ensure there can be no perfect curriculum. More of one subject or more extracurricular activities are likely to mean less of other things because the school day is not infinitely expandable (and there is nothing here to free up teachers’ time or fill in all those teacher vacancies). Yet the school curriculum does need to be revised over time to ensure it remains fit for purpose.

The question now is whether the CAR report matters. Will we still be talking about it in 20 years time? Can a Government buffeted by all sides, facing a huge fiscal crisis and with a Secretary of State for Education who sometimes seems more focused on political battles (like the recent Deputy Leadership election of the Labour Party) than on engaging with the latest educational evidence really deliver Becky Francis’s vision? Or will the CAR’s proposals wilt as quickly as the last really big proposal for curriculum reform: Rishi Sunak’s British Baccalaureate? In all honesty, I am not certain but there are, in theory at least, four years of this Parliament left whereas Rishi Sunak spent more like four months pushing his idea.

My parting thought, however, is different. It is that, while the trade-offs in the CAR report partly just represent the facts of life in education, they do not entirely do so. Trade-offs are much trickier to deal with when you are also seeking to root out diversity of provision. And in the end, if there is one thing that marks this Government’s mixed approach to schooling out above all, it is the desire to make all schools more alike, whether that is reducing academy freedoms, micromanaging the rules on school uniforms, defunding the IB, forcing state schools to stop offering classical languages or pushing independent schools to the wall. Would it be better, and also make politicians’ lives easier, if we stopped pretending that the 700,000 kids in each school year group are more like one another than they really are?

Postscript: While the CAR paper is infinitely more digestible than the interim document, there is still some wonderful eduspeak, my favourite of which is:

A vocational qualification is aligned to a sector and is usually taught and assessed in an applied way. A technical qualification meanwhile has a direct alignment with an occupational standard. Despite the name ‘Technical Awards’, these qualifications are therefore vocational rather than technical.

Comments

Jonathan Alltimes says:

We can not see the wood for the trees.

“In many respects, the material on 16-to-19 pupils is the least interesting part of the report – especially as there is next to nothing at all on A-Levels. The review team starkly states, ‘we heard very little concern regarding A Levels in our Call for Evidence and our sector engagement’, so they basically ignore them – in a world of change, A Levels continue to sail steadfastly on.” The question is why? There are two conditions which mitigate against reform, both are financial, first the vested interests of a multi-billion pound education industry and second, the government has no money to fund reform. Given these conditions, we should only have expected minor reforms, which is what we have been given. The value of GCSEs is essentially a ticket for A-levels and then academic higher education. Major reforms here would also be a lot of work for the schools and the universities.

The analysis of the report is completely acausal and ahistorical, their core argument essentially relies on a set of comparative OECD statistics as evidence. How the data points were generated in terms of real people is unknown. We know households are spending more and more money on private tutoring and home tutoring. We should be looking at comparative whole school examination performance in our own system of examination first to see if we have made improvements following earlier reforms, of which I could find nothing. Subject performance for GCSE has been reviewed by Alan Smithers, for example. Other OECD research has shown the high level of mismatch between employment and British qualifications, skills, and field of study.

In times past, it was possible for boys to study O levels for woodwork, metalwork, design and technology, and computer science. English, mathematics, a language, and a science were compulsory. History or geography could fall by the wayside. Some schools offered a broader range of technical and applied science subjects.

The subject requirements should be English, Mathematics or functional mathematics and data analysis, combined science or the three sciences, a technical subject, and geography or history (5 or 7) plus another 2 subjects for those who do not study the sciences, so the other subjects can be studied in greater depth and breadth. All of which would have consequences for the content of A levels. A chance to study two technical subjects and business would enable easier progression to BTECs. But that said, the IB is best the state sector could provide, given the funding.

The new V levels seem to be separating out the vocational routes from the technical routes of T levels, so as to remove confusion about pathways.

The introduction of a core non-assessed subject on digital technologies is going to be crucial for the future.

Reply

Add comment