Are EU students about to be treated like British students once more – and, if so, what will it mean for UK universities and students?

Responding to reports in the weekend’s newspapers that the negotiations between the UK and the EU could lead to big changes for universities and students, Nick Hillman, Director of HEPI, said:

‘The idea that students from the EU might come to be treated, once again, as home students when it comes to university tuition fees is superficially attractive. But as – seemingly – everything to do Brexit, it comes with a host of tricky implementation challenges. For example, unlike when the referendum happened, universities lose money on their home students and if EU students are to be treated like home students again, then institutions could likely lose even more money. They may need to respond by imposing a tight cap on the total number of subsidised places, which could have the effect of EU students displacing British students. Moreover, non-EU nations may seek their own favourable treatment in their own trade deals with the UK.

‘Similarly, rejoining Erasmus+ looks good on paper but the devil will be in the detail. As a country, we are woeful – and have been getting worse – at learning other languages. Spending time learning in another country provides wonderful opportunities and builds understanding between nations. However, we could have stayed in Erasmus+ plus when Brexit happened and we chose not to because it seemed an expensive programme that saw far more people arrive on UK shores than travel from the UK to study elsewhere. There was a stream flowing in one direction and only a trickle in the other, meaning the UK lost out financially.

‘Trade arrangements are reciprocal so it is important to ask what is in this wider deal for the UK’s cash-strapped universities as well as what UK students will get in return for EU students having cheaper access to UK universities.’

This morning’s Sunday Times reports that students from EU countries coming to the UK in future could become (re)entitled to the capped university fees that UK students pay. This means – in essence – that a French person pay less to study in the UK than a Chinese person. The newspaper suggests one motivating factor behind this possible change is the higher education choice made by one of Ursula von der Leyen’s children – such is the messy way that policy often gets made.

In his piece, the journalist Tim Shipman reports:

‘The UK has given ground on EU students in Britain and seems ready to let them pay the domestic rate of tuition fees, rather than the much higher international rate, which can hit £38,000 a year for the top universities. The UK will also rejoin the Erasmus student exchange scheme. The EU wants to scrap the entry fee levied on EU nationals for using the NHS. “The NHS fee is monstrous,” thundered one senior EU official, “and for a pretty mediocre service.”

‘Tuition fees was seen as a marginal issue by ministers, because the sums involved are not huge in the greater scheme of things. However, it is understood they ignored warnings from Lindsay Croisdale-Appleby, the British ambassador to the EU, who was quick to sense that the issue was important to Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission who has at least one child at university in England.

‘A Brussels-based source said: “It is not exactly a burning question for most Europeans but for the type of people around the table in Brussels university fees are a big deal because they want their kids to study in UK, especially at the more expensive Russell Group universities.”

‘Starmer will emphasise the defence aspects of the deal by hosting a lunch on HMS Sutherland, an antisubmarine warship moored on the Thames, before holding a press conference with von der Leyen in the Downing Street rose garden after 2.30pm. The commission had asked to go to a university instead of a military site to stress the youth mobility scheme.’

Such changes as giving EU students a right to the lower fees paid by British people or the UK rejoining Erasmus+ are not as straightforward as they might seem, even if they are only a small part of a new wider agreement between the UK and the EU. They raise a number of important questions.

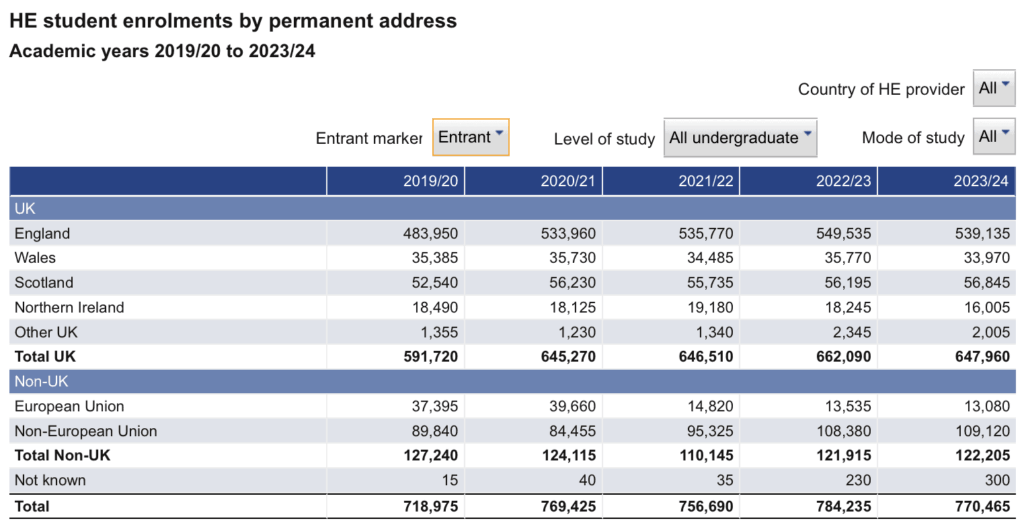

But let’s start with the basic fact that Brexit led to a sharp decrease in incoming students from EU countries. Looking at undergraduate entries alone, the table below shows the number fell from around 40,000 to under 15,000 in the year when the key Brexit changes took effect and the annual total now stands at about 13,000 or 1.7% of the total.

1. Is the change to fees restricted to fees or is it for fees and loans?

When the UK was in the EU and EU students got the same deal on fees as Brits, they received access to tuition fee loans as well as the right to pay a lower fee. In 2017 we showed in a HEPI / Kaplan / London Economics report (which accurately predicted the impact of Brexit on demand for UK higher education) that fee harmonisation for EU and non-EU international students combined with the ending of the loan access to EU students ‘would have an ambiguous effect on institutions.’

To put it simply, places like Oxford and Cambridge could still be sure to fill all their places and a higher proportion of their students would then be paying the full international fees rather than the capped fees – so an increase in the number of people entitled to lower fees could now mean a loss of income for them. For other institutions, there was a real cost to Brexit as students dropped away, meaning a predicted £40 million decline in university finances.

In terms of modelling future demand after Starmer’s deal, we need to know whether the proposal is just about fees or whether it is an attempt to revert to the full status quo ante whereby EU students can also access loans. Presumably, it is the former and EU citizens are not about to be given access to loans subsidised by UK taxpayers – thereby limiting access to UK universities to those EU students with access to enough upfront cash to pay both their tuition and maintenance costs for the length of their course. (If not, and if EU students are entitled to the loans once more, we will have the old problem of trying to recover loan repayments from people who have returned to their home country after graduation.) Some clarity is needed here.

2. Is the fee change for undergraduate courses only or for postgraduate courses too?

Most of the political fireworks around EU students have been around undergraduate courses, perhaps because undergraduate degrees are better understood than postgraduate degrees.

However, most international students in the UK are postgraduates, not undergraduates. It is probably easier for many people to travel for study when they are a little older and our relatively short Master’s programmes offer a particular appeal to some. It matters a lot to both students and universities whether the extension of capped fees to EU students is limited to undergraduate courses or is applied to all courses. For example, at one entirely randomly chosen course, a History MA at the University of Manchester, the fee for UK students is £13,000 and the fee for international students is £27,000.

3. What will the cost to universities be?

Back in academic year 2015/16, when the referendum happened, UK universities made a surplus of £200 million from their ‘publicly funded teaching’ (a category including UK and EU students entitled to financial support). To put it simply, back in 2015/16 fees of £9,000 (plus the teaching grant for more expensive subjects) covered the costs of teaching but today’s maximum fee of £9,250 does not. In fact, today, there is a deficit of £1,700 million for ‘publicly funded teaching’. So extending the lower fees to more entrants will cost universities money or, if they limit their intakes, could mean fewer places are available for home students as more places are taken by people from mainland Europe.

The issue could be most acute in Scotland – when we were in the EU, the disproportionately large number of EU undergraduate students in Scotland paid no fees even as their English, Welsh and Northern Irish counterparts did because EU rules meant home students (in this case, Scottish students) and EU students had to be treated the same – will this still be the case or will Scottish institutions be able to treat EU incomers like English incomers and charge them ‘Rest of UK’ fees, while also keeping them out of student number controls?

4. What are the costs of re-entering Erasmus+?

The real reason that the UK left Erasmus on Brexit was less to do with hatred of exchange programmes among Brexiteers and more to do with the fact that, for the UK, it was never an equal ‘exchange’. Far more students from other EU countries came here than UK students went there. As the Politico website reported last year:

‘The U.K. decided to leave the EU’s Erasmus+ student exchange scheme because Brits’ poor foreign language skills made membership too expensive to justify, a senior British official has revealed.

‘Lower take-up of the scheme by British students compared to other nationalities — put down to a weak aptitude for language learning — meant London expected to pay in nearly €300 million more a year than it received back, Nick Leake, a veteran senior diplomat at the U.K. Mission said this week.’

5. And finally, we need to think through the consequences for other trade deals.

There was a logic to charging EU students less when we were in the EU club / family, even though it tended to mean people from richer western countries paid lower fees to study in the UK while people from other poorer countries paid full whack. But outside the EU, the case may be less strong for offering people from the 27 EU states much lower fees than those from other countries just because the UK has an ‘agreement’ with the EU. If you were in another country and in the midst of negotiating a trade deal with the UK, you would surely be seeking reasons of your own why people from your country should also pay lower fees as part of your trade deal with UK, perhaps because of historic ties, or membership of the Commonwealth or some such.

Postscript: One other aspect that will need to be considered in due course is the operation of any new levy on international students of the sort floated in the recent migration white paper. If EU students are to sit somewhere between home students and international students, will they be subjected to the levy or not?

Comments

Anna Perry says:

2 points:

– of the 13,000 or so new EU undergraduates still enrolling in UK HE each year, an unknown but not insignificant proportion are UK or Irish nationals (or children thereof) resident in the EU and liable for Home fees (this agreement is due to expire in 2028)

– EU students may be able to take out loans and even be liable for grants from their home countries for study overseas. At the higher UK international fee rate such loans/grants might be insufficient but at the Home fee rate they may go some way to offsetting costs otherwise met by parents

Reply

Martin Hyde says:

Perhaps cut the requirement for them to pay the IHS (allow them to use their own private insurance or simply use their EHIC), and cut the need to apply for the student visa with accompanying fee. They could come to study with the new ETA if they have a university offer perhaps? For an MEng student this would be a reduction in cost of applying of £3,982 for a standard visa service and by £4,982 for a priority service. It would eliminate a substantial barrier. Universities can be free to set their own fees for various groups of students according to who they wish to attract (by bursary and scholarships) and they can be up to them and according to market demand. They do this already so this can simply continue. No need to interfere I think. If a university finds it a benefit to their institution to have more EU students they can design their fee structure to attract them.

Reply

Jack says:

Or like myself UK national who came back to the UK for uni from the EU (where I have lived for the entirety of my life) and who is being treated like a International student. Which is also a big issue that is affecting a lot of British nationals.

Reply

Rafael C. says:

I don’t believe EU students have stopped coming to the UK for any reason other than the cost. If postgraduate programs are not exempt from the high fees that contribute to the UK’s HE deficit, then many students will simply choose to pursue their degrees in the EU. This agreement will not solve the financial crisis facing the UK higher education system, not make it significantly worse.

There is no excess capacity at UK universities. Until recently, UK student tuition was being subsidized by international students paying higher fees. Now, the system is being propped up not only by those international students but also by staff—who are working more for less pay and fewer benefits. EU students are about to become part of the group that is effectively subsidized if they pay UK nationals fee.

In my view, this model is not sustainable—which is something UK universities are expected to be. At some point, international students will realize that they are being exploited and will opt out, or staff will leave because they simply can’t afford to live and work in the UK under these conditions.

I understand the hesitation to fund the education of UK students directly, but the British government has placed that financial burden on international students—and now on university staff—for far too long and to an excessive degree. Would you continue paying three times more than your neighbor for the same service just because you were born in a different country? Would you keep working longer hours for the same pay, despite inflation, simply because your employer is restricted from raising prices for a decade?

The British government must recognize that international students and university staff are not responsible for covering the costs of benefits enjoyed by British society—whether that’s students, businesses, the government, or the public. The sooner this is acknowledged, the less long-term damage will be done to the UK’s higher education system. Unfortunately, that damage has already begun. We are only months away from some universities collapsing entirely.

Reply

Jo says:

I am a British citizen and my son is a British citizen, born and raised in Hong Kong. We came back to the U.K. 2 years ago and have found we are priced out of U.K. universities as British citizens who have not lived in the U.K. for 3 years before going to Uni are subject to overseas fees.

EU universities are much cheaper (£12-15k instead of £30-38 per year) and further up the rankings, but this is still money we would not have to pay if Britain was in the EU and our son would not have to worry about getting a work or student visa – student visas are £200 per country, and because universities give offers at different times, we have to accept for Holland now and pay around £30k + the student visa to hold the place because we are no longer in the EU, in case an offer does not come through from Denmark in July.

I hope that full access can be restored for EU students coming to the U.K. and for Brits going to EU universities. I’d also like the freedom to work as an English teacher doing my own courses anywhere in the EU.

Reply

Karen Hardman says:

University education in Germany is completely free apart from a very small admin charge of around 300 euros per year and in many other EU countries,the same also in Scotland.

Why anyone from an EU country would want to come here and pay an extortionate amount of money is completely beyond my comprehension!

Reply

Maria says:

We don’t have Erasmus now but bilateral agreement,we have much less choices and perks compared Erasmus

The uk students lose always.

Reply

Tahir Mehmood says:

It is very unfortunate that we never truly left the EU and that we have now rejoined the EU. There was always more EU students coming to the UK than the other way around. Quite how the EU could say that it is a reciprocal arrangement benefitting both sides when it has always been the case that more of them come to the UK than the other way around putting pressure on public services especially housing. This argument that UK students don’t study in EU countries is because they can’t speak a foreign languages is not correct. There are plenty of countries in the EU and in the world generally who cannot speak another language other than there own. The reason why EU students come to the UK is because they have better job opportunities than in their own countries and we have better universities than most of them. Similarly with the fishing industry the EU rather than buy our fish simply want it for free by treating British eaters as international waters instead. Labour are finished. Reform will take over at the next election unless the Tories bring back Boris Johnson and truly Get Brexit Done.

Reply

Janvi Patel says:

I am a British national living in the US. My children (also British Nationals) would be considered international students, but EU nationals would be (re)entitled to the capped university fees that UK students pay. How does that make sense?

Reply

Magda says:

Coming from the EU, I got an offer from Cambridge to read Medicine last year and due to the enormous amount I was forced by circumstances to give this up.

I will be looking forward to hearing more about this, hopes this comes through and people who come after me stand an actual chance of getting their dream education.

Reply

Jonathan Lewis says:

If one of the rationales for this reconnection to the EU is to remedy the dwindling number of students attending Uni in the UK, why not also consider lifting the 3 year residency requirement so that Brits living abroad can afford send their kids “home” for Uni? Or at the very least offer some kind of intermediate price, so that such Brits don’t have to pay the same international fees as, say, the Chinese?

Reply

Kevin says:

I totally agree. It’s ridiculous that British citizens living overseas are considered international students. In fact, I’d pursue graduate studies in the UK if the government removed that 3 year residency requirement.

Reply

Add comment