Would leaving the EU really mean fewer EU students coming to study in the UK?

HEPI is a registered charity, regulated by the Charity Commission. It does not take a position on the UK’s continued membership of the European Union. Instead, it exists to promote healthy debate on issues associated with higher education.

In relation to the referendum, this has so far included:

- commissioning a survey and writing a report on students’ views on the UK’s membership, as well as on their likely behaviour on Referendum Day and their views on how their institutions should act in the run up to 23rd June, when the vote takes place; and

- hosting a seminar jointly with the Higher Education Academy at Parliament, where the speakers were a Professor of European Studies from the University of Oxford, the Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Glasgow (with first-hand experience of the recent independence referendum there) and a political scientist from the University of Manchester.

There were welcome messages for both sides of the debate in these activities, though the Remain side may have found somewhat greater sustenance. For example:

- 70 per cent of students told us they intended to vote for the UK to remain inside the EU, were a referendum to be held tomorrow (fieldwork: October 2015), although there was a soft underbelly to this position; and

- at our seminar, we were told that – while the polls, especially the Internet polls are close – in the majority of comparable modern referenda, there has been a swing to the status quo in the run up to the day of the vote and that opinion polls often underestimate (and seemingly never overestimate) the support for the status quo option.

We will go on seeking to be even handed by encouraging debate. As part of this, we will consider drawing attention to some of the claims being made that link to higher education.

One of the most common, is the claim that – thanks for our EU membership – lots of EU students have chosen to come and study here. There is some truth in that. The lack of a need for a visa, for example, and our relatively short Masters programmes are strong pull factors, as is the English language and the reputation of our higher education sector. Moreover, the EU’s Erasmus+ scheme facilitates the mobility of students and staff (among other things), although it is important to note that many non-EU states participate in the programme too.

Yet, despite this, it is also worth remembering that until the recent abolition of student number controls, there was actually very little incentive to recruit people from other EU countries straight on to undergraduate courses. When each institution could be penalised for over-recruitment and there were sufficient numbers of home students to fill the whole system, going out of your way to recruit EU students just looked like a costly and not-very-worthwhile exercise. For most of our EU membership, recruiting EU students has been less enticing than recruiting other international students. This is because, unlike other international students, they filled your fixed number of places and paid you less than other international students (and the same as easier-to-find home students) for the privilege.

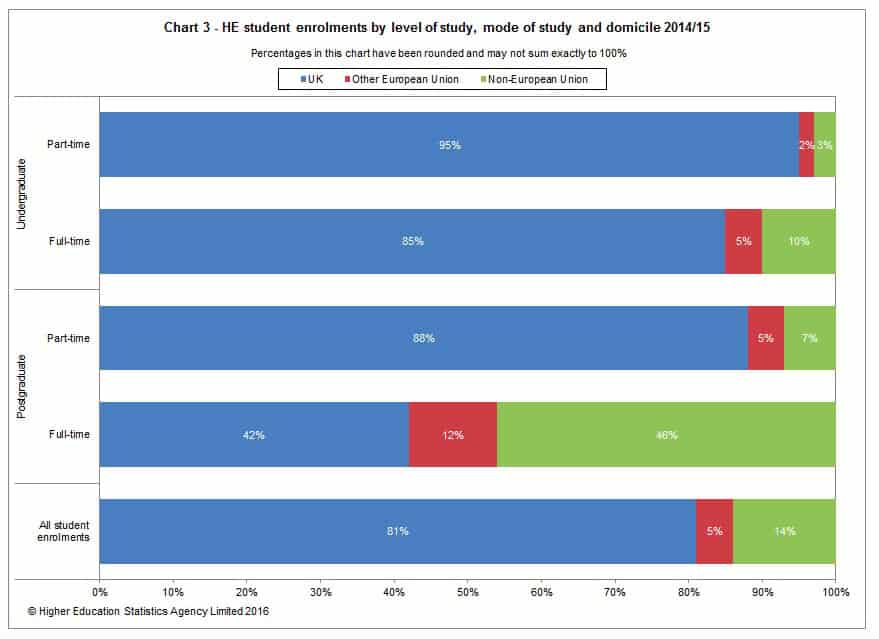

This helps to explain why the latest figures from HESA show that, in 2014/15, non-EU international students made up 14% of total student enrolments but students from the rest of the EU made up only 5%. While only one-in-20 full-time undergraduates were from the rest of the EU, twice as many – or one-in-10 – were from non-EU states. Even among full-time postgraduates, just 12 per cent were from the EU compared to nearly half (46%) from the rest of the world.

This picture is changing because the student number cap was recently removed. University recruitment is not a zero-sum game any more: no longer does each extra EU undergraduate displace a home one. As a result (and as we predicted), the number of EU undergraduates is now growing fast, albeit from a low base. UCAS’s last End of Cycle Report found:

‘Acceptances from the EU increased by 2,900 (11 per cent) to 29,300. This is the largest single year increase seen in the reporting period and highest total of EU acceptances. The increase results from both an increase in applicants (+8 per cent to 50,700) and an increase in their acceptance rate (by 1.5 percentage points to 57.8 per cent).’

This makes sense because recruiting more EU students can be a good way to protect or even raise the quality of courses as well as the quantum of students – not to mention institutional income.

While this policy lasts, those hoping the UK will stay in the EU may well be right to say that our membership of the EU is encouraging people to come and study here – even if the recent rapid growth rate is new. As a result of free movement rules, not only do EU citizens have their fees capped at £9,000 (in England – fees are less or non-existent in the other parts of the UK) but they can also access a full fee loan, so there are no tuition costs to pay upfront (though maintenance still has to be covered).

This makes our lecture halls more diverse and boosts the UK soft power, which is welcome and our evidence proves the benefits are recognised by home students. But it does bring the challenge of collecting repayments from EU citizens who come here to study only to leave swiftly afterwards. Personally, I hope the removal of student number controls does indeed last, but some people think it is inevitable it will not. Bahram Bekhradnia, HEPI’s own President, has claimed the initiative ‘will end in tears’.

It seems obvious that leaving the EU and starting to treat citizens of EU states the same as other international students (meaning higher fees, no access to tuition fees loans and so on) would reduce their numbers dramatically. Perhaps so. According to the House of Commons Library:

‘If the UK withdraws and EU students are classed in the same way as overseas students and charged higher fees, this could have an impact on numbers coming to study in the UK and on fee income for universities.’

Yet there is one precedent that suggest this might not happen.

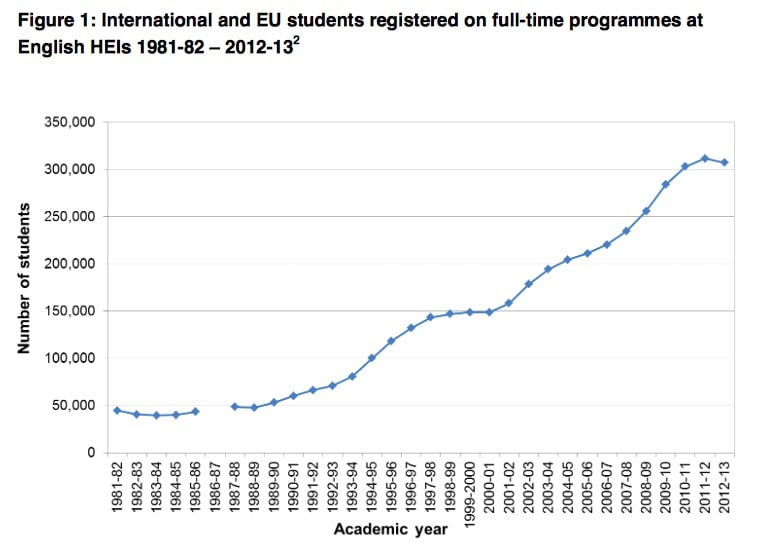

International students used to be able to study in the UK at minimal cost. The price of coming to study here gradually increased from the 1960s onwards, under both Labour and Conservative Governments. In 1980, Margaret Thatcher’s Government abolished the subsidy for international students altogether, so their fees leapt up to the true cost – or higher. At the time, it was claimed the number of international students would collapse. In fact, as shown in the chart from HEFCE reproduced below, the numbers declined a little before soaring as the financial benefits to institutions of actively recruiting international students became clear.

Perhaps this precedent is irrelevant. History does not always repeat itself. But it is still notable that the number of EU applicants has risen every year since 2012, when fees rose from a little over £3,000 to £9,000, and is already higher even than in 2011, when people rushed to enter before the higher fees came in.

Comments

Add comment