Why the Office for Budget Responsibility is almost certainly wrong

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) makes forecasts for future student numbers because of the knock-on consequences for public expenditure.

I have pointed out the apparent pessimism in their forecasts more than once before – see here and here – and have also visited them to discuss their figures.

We are raising the issue again because the OBR have just downgraded their assumptions to make them even more pessimistic. In the new Economic and fiscal outlook, published alongside the autumn statement, the OBR states: ‘Reflecting the latest UCAS acceptances data, we have revised our forecast for 2016-17 student numbers in England’.

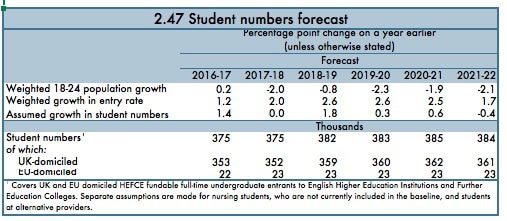

The OBR’s new forecasts assume an increase of 9,000 students, from 375,000 to 384,000, between 2016/17 and 2021/22 – around 2.5% over the whole period. This is under 2,000 a year new higher education entrants on average, although the growth is not predicted to be spread evenly: for example, the OBR assumes no growth whatsoever in 2017/18 and a decline later in 2021/22.

It is not totally clear which students are counted by the OBR and which are not. But the figures are broadly comparable to UCAS’s figures for ‘placed applicants from England’ in 2015 of 394,400. This is a very incomplete starting number as only some students are counted in this UCAS figure, mainly English students attending UK higher education institutions on a full-time basis. Overall, UCAS place over half a million students a year and even that does not represent the total number of new entrants.

If the OBR’s starting point is strange, their modelling is even odder. While it focuses on demographic assumptions and trends in application and acceptance rates, it ignores other factors that can affect demand for higher education.

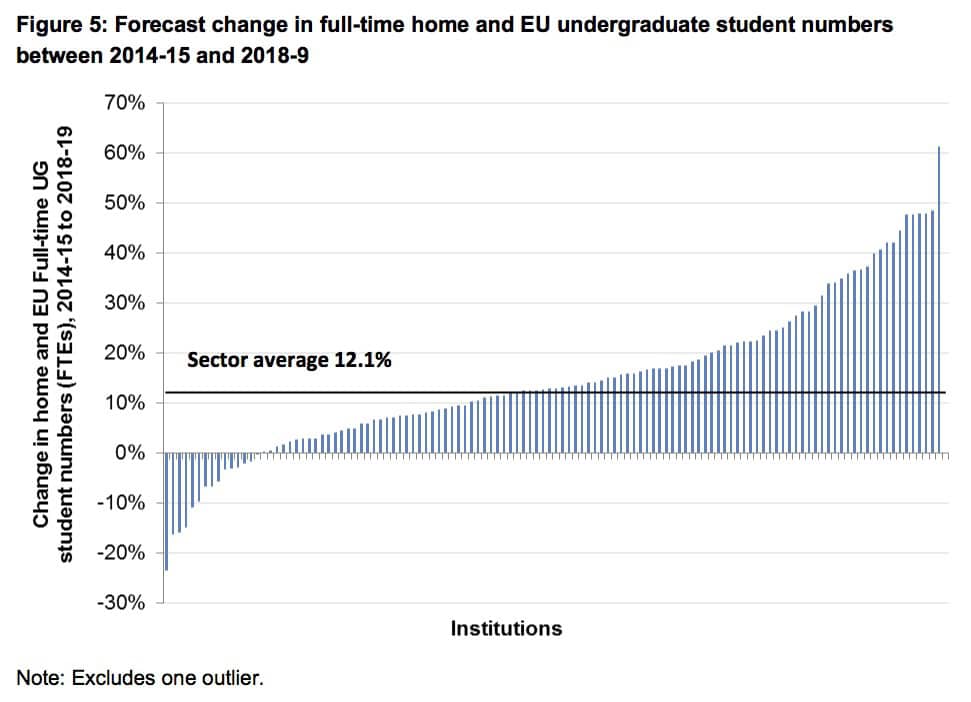

This helps to explain why the figures are so out of line with higher education institutions’ planning assumptions, as shown in the data they have submitted to the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). In a recent report, HEFCE showed that higher education institutions expect to see a 12.1% increase in the total number of full-time home and EU undergraduate students, albeit over a different but overlapping period (2014/15 and 2018/19).

To be fair, HEFCE warns the data they have received from universities may turn out to be overly optimistic:

There are risks relating to the realistic achievement of this growth, however. These include:

- whether there will be sufficient growth in demand for undergraduate courses to overcome the declining population of 18 year-olds (ONS data projects a decline in the 18 year-old English population of 9.1 per cent (or, taken together, an English and EU decline of 1.8 per cent) over the forecast period

- any negative impact of Brexit on EU student recruitment

- increases in alternative training routes to undergraduate courses.

But is there anyone in the higher education sector, I wonder, who thinks it is likely that the growth in full-time undergraduate numbers will be as low as the OBR says? After all, it works out at under six extra new students annually for each of the 344 institutions that HEFCE funds.

That seems implausible to me. The OBR are admirably keen to engage with people when their numbers are challenged. So perhaps they can clarify why they are so pessimistic and also provide some reassurance that they will talk to the sector when undertaking similar modelling in the future.

Comments

J. Dyson says:

The OBR don’t seem very clued up on how HE works, it makes you wonder how unreliable the rest of their forecasts are.

Reply

Add comment