‘Forward, Together’ or ‘More of the Same’?

The official title of the Tory manifesto is, perhaps surprisingly, not ‘Strong and Stable’ but ‘Forward, Together’. Given that the Conservatives have been in office, in coalition or on their own, for seven years already, one could be forgiven for thinking it might have been ‘More of the Same’.

There are the same commitments that we have heard before on reducing migration, on expecting universities to sponsor schools and on doing more to help white working-class boys.

But actually, on closer inspection, the manifesto seems to be at one with the wider Conservative election campaign in putting a new foot forward. That is almost certainly for the best because the Parliament we are about to elect is the one that will need to see Brexit through, for good or ill. The only certainty is that post-Brexit Britain won’t be identical to the pre-Brexit Britain.

So past vague commitments to maintain science and research funding have been replaced by a bolder commitment to increase the UK’s total research and development spending to the OECD average of 2.4% of GDP in the medium term and (ironically, given we are leaving) to the EU target of 3% of GDP in the longer term. Many people in higher education won’t believe that until it happens, though it is hard to doubt the scale of the ambition.

Another change of direction is the emphasis on technical education. One reading of the manifesto is that funding will be rebalanced towards further education. For example, there is a promise of ‘a major review of funding across tertiary education’, some training colleges will get degree-awarding powers and – shhh, don’t tell Her Majesty the Queen just yet, as she would need to agree – there could even be new ‘regius professorships in technical education’.

This could all be interpreted as the recreation of the old binary system with degree-awarding technical institutions sitting alongside traditional universities. Or, alternatively, some are seeing it as a backdoor raid on higher education to fund other priorities. Presumably, someone in Number 10 has been reading a recent report by Alison Wolf, who is something of a guru in Conservative circles.

Yet to interpret it in such ways would be to downgrade the level of thought behind the new commitments and to miss the manifesto’s true significance. If the UK is both to leave the European Union and to welcome fewer migrants, then we need a step change in the way we train people already resident here. In other words, it seems to me that the new commitments on technical education are less tactical and more strategic than many people have given them credit for. Instead of withdrawing from Europe first and worrying about the supply of skilled labour second, Theresa May seems keen to start raising domestic skill levels even before we leave the EU club.

Another important area where a change of direction is proposed is on the training of teachers. As we argued in our most recent report at the end of last month, we are on the cusp of a crisis in teacher supply, partly caused by the unpopular shift from university-based teacher training to school-based teacher training. Our paper, written by John Cater, criticised the current bursary system and called for ‘the possible introduction of “forgivable fees” for those who remain in teaching for a number of years’. The manifesto says, ‘To help new teachers remain in the profession, we will offer forgiveness on student loan repayments while they are teaching’. Those who have looked at the issue closely will tend to agree that this is a smart response to the growing shortage of classroom skills.

Finally, the thorniest single issue for the higher education sector in the Conservative manifesto is the issue of international students. The paper promises that a future Conservative Government will ‘toughen the visa requirements for students’ – to which Universities UK immediately and pointedly said, ‘We will continue to make suggestions on how the immigration system could be reformed to make the UK the most attractive destination in the world to study.’ The manifesto’s approach might be caricatured by some as ‘Forward, Alone’ more than ‘Forward, Together’ but, either way, student migration looks set to remain the one area where the higher education sector and the Conservative Party are most out of kilter with each other.

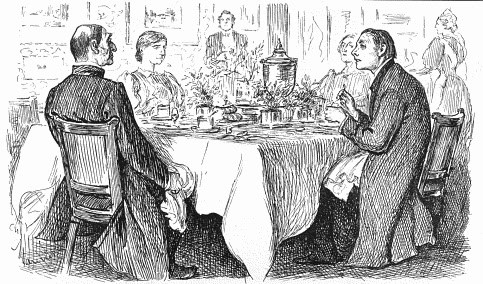

In 1895, the magazine Punch famously published a cartoon of two clergymen eating breakfast. When the bishop pointed out that his guest, a lowly curate, was eating a bad egg, the nervous junior replied: ‘Oh, no, my Lord, I assure you that parts of it are excellent!’ For many people in higher education institutions, the manifesto of the party that seems certain to win the general election probably resembles that curate’s egg more than anything else.

Comments

Add comment