The hallmarks of a successful university

The following text is a transcript of a speech made earlier today by HEPI Director of Policy and Advocacy, Dr Diana Beech, to the University of Salford’s Student Housing Conference.

I have today been asked to speak on what it takes to create a world-class higher education institution, looking at what the hallmarks are of a successful university and how you can make yours stand up to the demands of the twenty-first century.

As we stand at the start of 2018, there can be no doubt that we are not just entering a new year but also a new era for higher education policy, in which the student experience is becoming central to conceptions of what constitutes a ‘successful’ university.

As Big Ben struck midnight on 1st January, the new market regulator for higher education in England, the Office for Students (OfS), came into existence. As its name suggests, the OfS will seek to regulate English higher education institutions by putting the interests of students at the heart of the system. Earlier this month, we also welcomed a new Universities Minister, Sam Gyimah, who said at a Mile End policy event after assuming office that his main priority was to ‘deliver for students’, ensuring they had ‘real choice, transparency and value for money’ and the chance to ‘participate fully in university life’.

What it will take to succeed in this new regulatory landscape, therefore, will very much depend on:

- the services that institutions provide to students;

- how they roll out these provisions;

- who they reach; and

- the impact they make on students’ learning gain, welfare levels and eventual employability prospects.

Universities which put students first look set to become the success stories of the future. But what exactly does it mean to put students first? And how can, and should, universities be doing this?

To answer these questions, we first need to take a step back and look at what it is that students appreciate in their higher education experience. Fortunately, HEPI and the Higher Education Academy (HEA) have been tracking students’ sentiments about their university experience for some time in the annual Student Academic Experience Survey. As the largest survey of its kind, running for the past 10 years, the Survey tells us what constitutes a ‘positive’ higher education experience for students, broken down by value for money, learning gain, wellbeing and the extent to which experience meets expectations. Taking each of these factors in turn, we are able to observe some key trends.

Value for money

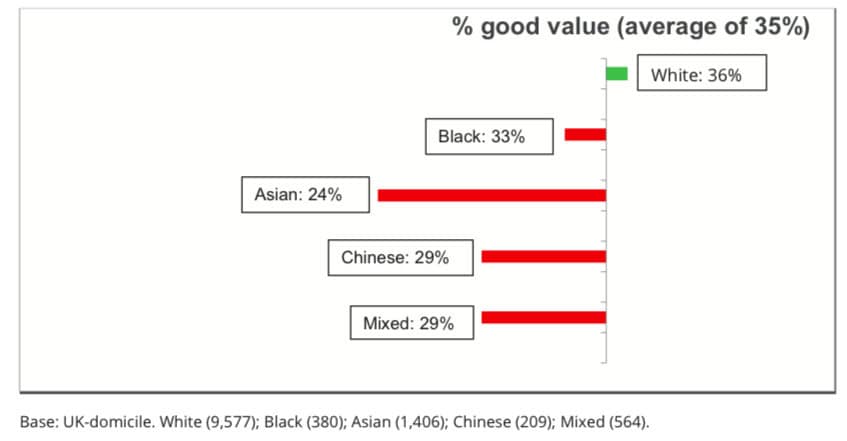

When it comes to perceptions of value for money, students on courses with a wide variety of teaching methods and contact hours (such as Medicine & Dentistry) generally report higher levels of value for money, compared to those on courses like Social Studies or Business. Students from Russell Group institutions are also more likely to feel they have received good value for money for their higher education, compared to those from other pre-92, post-92 and more specialist institutions. (It is nevertheless worth acknowledging that for all the main institution types, value for money perceptions are still lower than 40% across the board.) There are also significant variances between different ethnic groups, with students from (non-Chinese) Asian, Chinese and Mixed backgrounds perceiving they have received lower value for money than their White counterparts (as shown in the chart below).

Learning gain

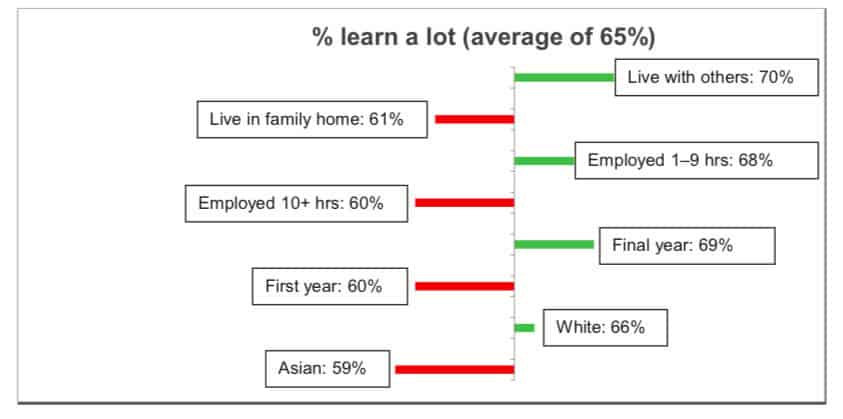

These findings can be closely correlated to perceptions of learning gain. Fortunately, two-thirds of students surveyed in 2017 feel they have learnt a lot from their higher education experience. However, when we look at the types of students reporting the most learning gain, they are generally students:

- who are living on campus with others;

- engaged in paid employment for less than nine hours per week;

- in their final year of study; and

- White.

Those reporting lower levels of learning gain are, by contrast, students:

- who are living in the family home;

- engaged in paid employment for 10 hours or more per week;

- in their first year of study; and

- Asian.

This is shown by the following chart:

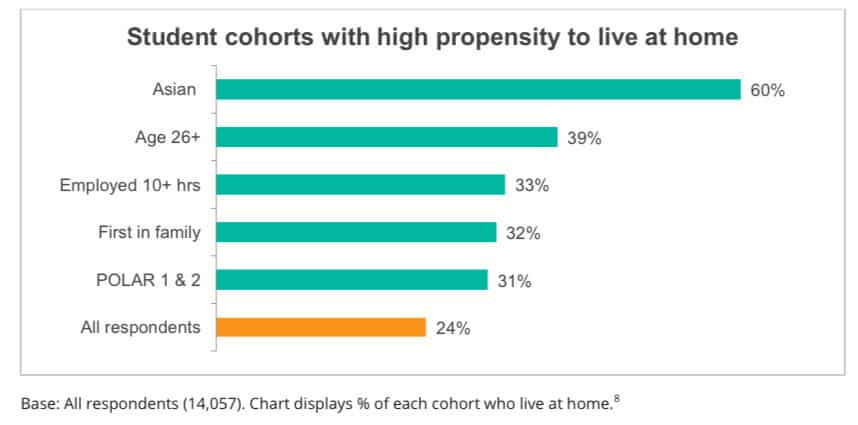

So, not only can we see Asian students reporting the lowest perceptions of value for money from their higher education experience, but also the lowest levels of learning gain. We know from additional analysis that Asian students are also most likely to be ‘live at home’ students. As the chart below illustrates, these are followed closely by ‘mature’ students (i.e. those aged 26 and above), ‘first in family’ students and those from less affluent backgrounds.

Wellbeing

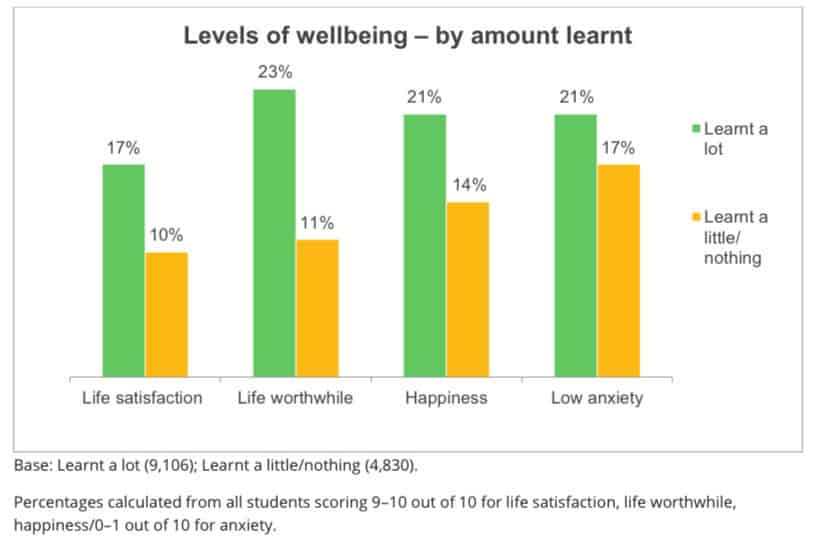

With live at home students reporting lower levels of learning gain, we know that they are also the cohort of students most likely to report lower levels of wellbeing. Data from the 2017 Student Academic Experience Survey reveals only 14% of students reporting low levels of learning gain said they were happy, only 11% felt their life was worthwhile and only 10% experienced life satisfaction. These findings are in line with existing evidence which shows commuter students tend to find life unexpectedly ‘tiring, expensive and stressful’, often lacking a sense of security and a firm place of belonging.

Experience vs. expectations

Live at home students are also much more likely than average to say that their experience of higher education has been worse than they had expected – 18% compared to 13%. Some of the reasons for this reflect a sense of isolation and disconnection from the campus and university staff. Most tellingly, 57% of live at home students who felt their higher education experience had been worse than expected cite too little interaction with staff as being the cause of their discontent. What these figures show us, then, is that a sense of connection to a university really does matter to a positive student experience.

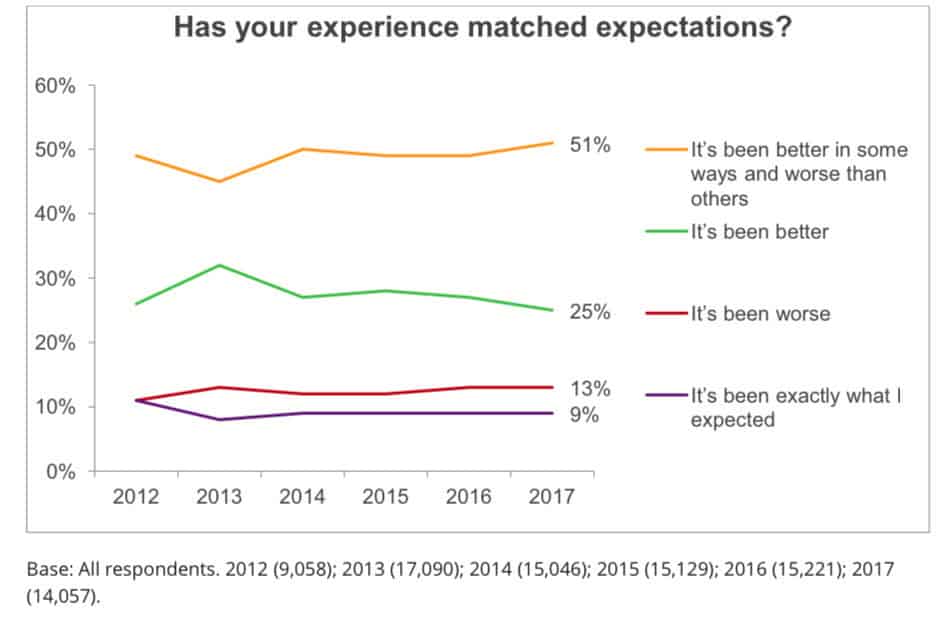

Commuter students are, however, not the only students who feel their expectations are not being met. Data from the 2017 Student Academic Experience Survey show that, since 2015, there has been a downward trend in the number of students overall perceiving their higher education experience to have been better than expected, while the number of students saying it has been worse than expected has plateaued.

This suggests students living on campus are expecting provisions that universities are ultimately failing to deliver.

What applicants want

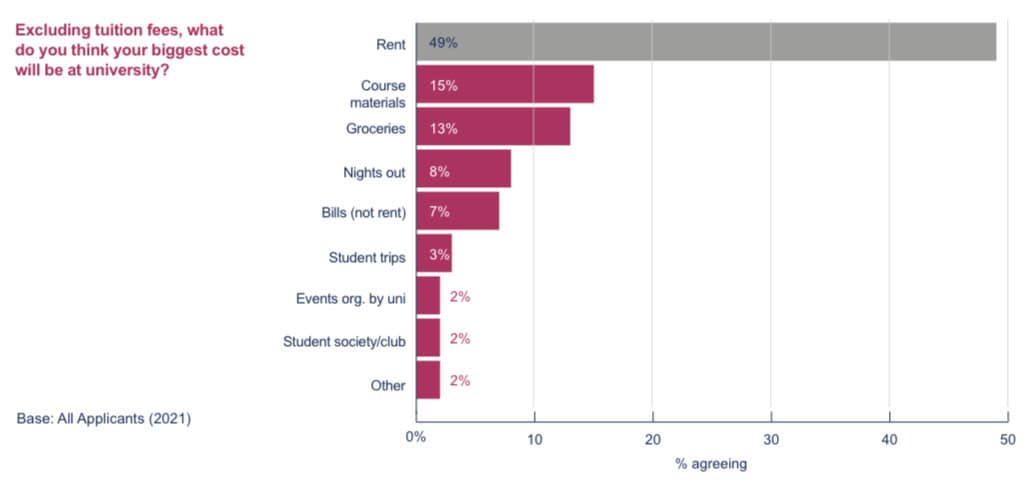

Last summer, HEPI – in conjunction with Unite Students – looked into what it is that university applicants are expecting from their higher education experience in our Reality Check report to try to get to the bottom of this sense of dissatisfaction. What we found is a significant gap between what university applicants think higher education is like and the realities of student life. We found, for example, that applicants severely underestimate the essential costs of university life, such as rent, with just under half (49%) of university applicants thinking rent will be their biggest expense aside from tuition.

The fact that more than half (51%) of applicants do not realise that accommodation costs will be their biggest expense suggests universities and accommodation providers need to be doing more to work with prospective students, schools and their parents to provide a smoother transition into the realities of university life, including better pre-arrival communications.

Accommodation matters

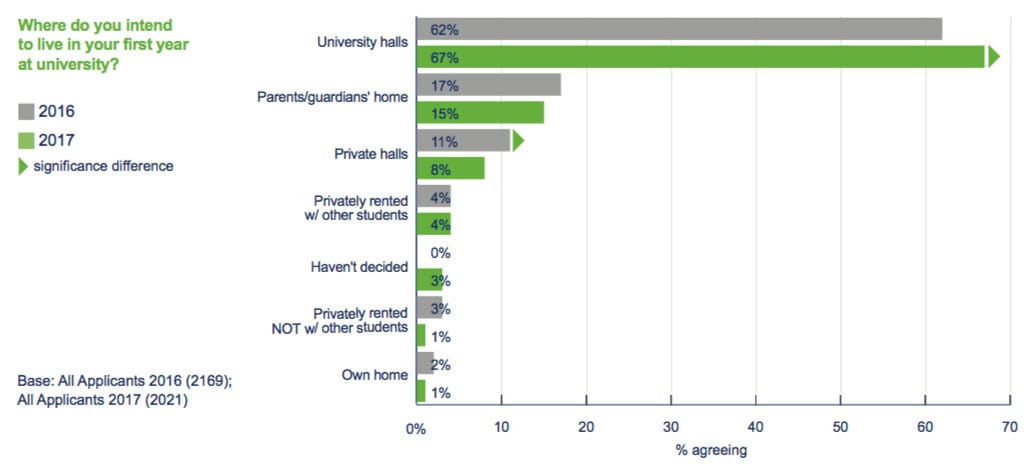

Even if they do not fully appreciate the costs of campus living, the majority of applicants at least recognise the importance of student accommodation for their social integration and potential to make friends while at university. Living in shared halls of residence was the top choice of first-year accommodation for applicants, with over two-thirds (67%) intending to live in halls.

About half (47%) of these applicants nonetheless have some degree of anxiety about the prospect of living with people they have never met before, illustrating the importance of providing support for students during the ‘settling in’ process. Moreover, students identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual or other (LGBT+) feel more anxious about living with strangers and are less confident about making friends, once again highlighting the importance of providing tailored support to certain subsets of students.

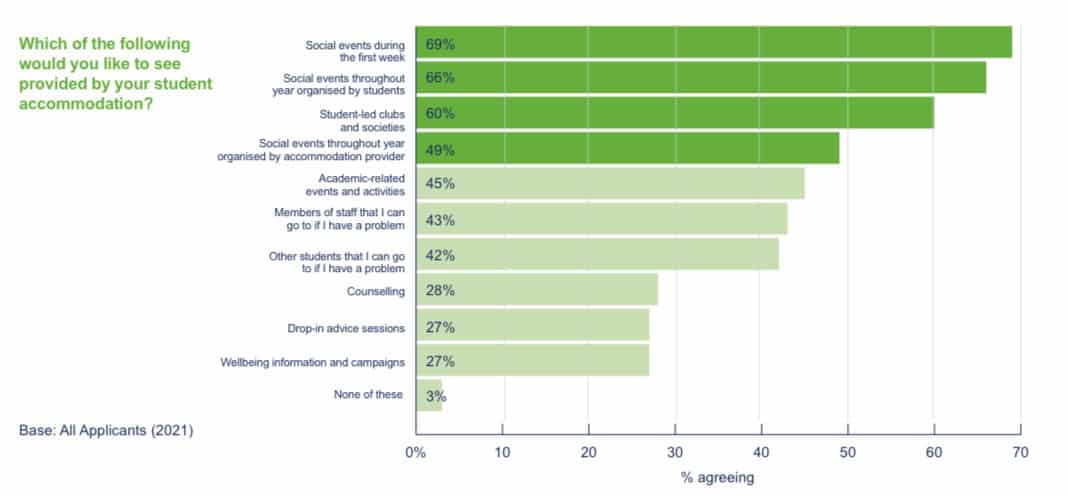

Overall, our data show that applicants view student accommodation as much more than simply somewhere to live, but as places where they can integrate with others and as openings to the ‘true’ university experience. Two-thirds (66%) of applicants said they would like to see student-led social events held throughout the year in their student accommodation and 60% would like to see clubs and societies using university accommodation for events.

Expensive taste?

Students’ recognition of the social benefits which additional provisions bring to their higher education experience is reflected in their willingness to pay for a ‘better’ standard of accommodation. At the 2016 Property Week Student Accommodation conference, Paul Humphreys (founder of the student review site StudentCrowd) said that mid-market halls were the least liked by students. Halls which cost between £98 and £135 a week outside London were the worst reviewed on his site, based on several measures including value for money, social experience and facilities management. By contrast, the cheapest halls (i.e. those costing less than £97 a week) were voted the best value for money and best for social experience, while the most expensive halls (i.e. those over £135 a week) were also voted good value for money, showing students recognise additional facilities are worth paying for if they enhance their university experience.

The importance of being sticky

Going back to working out what the hallmarks are of a successful university, then, we can see that the successful institutions of the future will be ones that recognise there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution to improving the student experience and will endeavour, therefore, to offer support to two very different broad subsets of students – namely those living at home and those living on campus. What these two very different student groups have in common, however, is the desire to be better connected to the benefits of university life.

For commuter students, this means finding ways to entice them to stay on campus, use the facilities and partake in extra-curricular activities. One way of tackling this issue is by creating a ‘sticky campus’ and implementing measures that encourage students to feel connected (or ‘stick’) to their institutions. Some universities already experimenting with the ‘sticky campus’ approach include the University of Manchester with its Living at Home Students officer in its Students’ Union, and also Abertay and Staffordshire universities. Initiatives could be as simple as putting sofas in academic departments to encourage students to stay and socialise or wait for academic staff outside lecture hours to receive the support they need. Building strong ‘staff-student’ networks could be another way to ensure live at home students get the academic support they require.

For students living in halls, this means not just providing first-rate facilities but enhancing their accessibility and usage. This was a theme which came out strongly in last year’s provider submissions, submitted as part of the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) assessment process. Analysis of the submissions in a HEPI report reveals some of the most influential statements were written by institutions which demonstrated how they involved students in the design process of facilities or engaged students in continuous dialogue via consultations and committees. Enhancing usability nevertheless requires effective join-up between universities, students’ unions and accommodation providers.

Can we learn from boarding schools?

Meeting the requirements of two very different types of students is admittedly a daunting task but is in no way impossible. In November last year, HEPI Director Nick Hillman asked in a HEPI blog if there is anything we can be learning from the boarding school model of education, where ‘day boarders’ effectively mix with conventional boarders, yet all feel a deep sense of belonging to their institution. One idea mooted in the blog was giving commuter students membership of halls of residence (and other forms of student accommodation), so that they have access to the facilities and the opportunities they bring for socialising with others – so, basically offering them everything bar the actual bed. As Nick argues: ‘it would cost little and could quickly pay for itself through better academic outcomes, more student engagement and lower drop-out rates’.

One extension of this idea could be keeping a handful of student rooms on campus in reserve, so that commuter students who find themselves staying on campus late can book a bed for the odd night. Some of these beds could be booked by students in advance so that they can make plans to attend social or sporting events in the evenings, while some beds could be booked on the night, so that students staying late after a long day of using university facilities, such as laboratories or libraries, know they have somewhere to go ‘in an emergency’. Offering such an option need not even require much space. Allowing commuter students to book beds in single-sex dormitories on a nightly basis, as is common in hostels, would not require much floor space, yet would offer students a place to rest, stay safe and socialise with others.

Positive universities

Ideas like this build on the ten-point plan for creating ‘positive and mindful’ universities outlined in a HEPI report written by leading educationalist Sir Anthony Seldon and the University of Buckingham’s Dean of Psychology, Alan Martin. It proposes introducing supportive measures for students including educating them about self-harm and financial literacy, as well as sessions on mindfulness and wellbeing for all first years. The report also advocates the appointment of personal mentors and offering alternative activities for those who may be daunted by the ‘outgoing’ nature of events traditionally offered by students’ unions. Some ideas include offering non-alcohol-based student activities and quiet rooms for relaxation and reflection.

Twenty-first century institutions

When it comes to making universities stand up to the demands of the twenty-first century, institutions which continually strive to improve the student experience – not just through teaching, but through all the facilities and services that make up university life – look set to become the universities of the future. Of course, there is an abundance of league tables which purport to tell students about which institutions are world-class, but they are based on limited criteria and, therefore, ignore many of the valuable features offered by institutions which cannot be easily measured or incorporated into the rankings. The Government’s Teaching Excellence Framework is no exception to this rule.

A new HEPI report offers advice about how best to approach some of these university ranking systems and cautions that they should be seen as just one part of a broad range of assessment tools. Given the growing importance of the student experience to the new regulatory landscape, however, and also the need to connect universities to the wider communities around them (something that was particularly exposed after Brexit), it is only logical that the future hallmarks of success in the sector may well be ones outside conventional league table rankings.

In an age of increasing uncertainty, both for individuals and wider society, the onus is most definitely on universities to work out how they can become positive places, not just for their students, but also for their wider communities, regions and the country as a whole.

Comments

Add comment