zhōngwén (中文): an opportunity the UK can’t afford to miss

This blog was kindly contributed by Megan Bowler, author of the HEPI Report A Languages Crisis?

HEPI’s important and timely new publication UK Universities and China raises important proposals on the need for the UK’s higher education sector to strengthen its collaboration with China and to provide a more welcoming environment for Chinese international students. Chinese language learning emerges as a priority for making progress towards these goals.

For instance, Professor Simon Marginson argues:

Western countries have lagged in acquiring Chinese, partly because China has done so well in learning European languages, but high calibre understanding and cooperation is impossible without language. The field is open: this could be a source of profound comparative advantage for the UK.

Improving the UK’s skills in Chinese languages, then, could give the UK a competitive edge in increasing new opportunities and research partnerships with China, particularly in science and technology fields, where China’s output continues to grow exponentially – China overtook the USA in 2018 for total scientific publications. In high-turnover fields like STEM, there is a need for new work to be translated rapidly and effectively, often requiring technical subject knowledge – it would hence benefit researchers to have proficiency in other languages and particularly written Chinese.

This year, the Covid-19 pandemic has also caused the publication language of scientific findings to become a politically charged issue in China. Chinese researchers were criticised for publishing in English-language journals during the early stages of the outbreak rather than disseminating information in Chinese languages which could have been put to use more quickly on the frontlines and helped to reduce the spread more effectively. This in turn is prompting an emphasis on using Mandarin even more so as a default publication language and challenging the traditional hegemony of English in science.

The British Council’s most recent Languages for the Future report also ranked Mandarin Chinese as the second most important language for people in the UK to learn. This cited the relatively low level of English proficiency in China, the high usage of Chinese on the internet, and the growing importance of Chinese in business (particularly post-Brexit) and for the higher education sector:

By 2020, China will be one of four countries accounting for over half of the world’s population of 18–22 year olds, making it a priority country for international education, not only because it has one of the largest education systems in the world but also because it is expected to send the most students abroad.

There are, therefore, a number of strategic reasons why the UK’s higher education sector stands to gain – both for research purposes, and for attracting students from China – from increasing opportunities to learn Chinese and to develop cultural knowledge.

Combating ‘linguaphobia’

Vivienne Stern and Yunyan Li’s essays in the new HEPI collection stress the importance of UK higher education institutions striving to welcome Chinese students, who account for nearly a quarter of the UK’s international students. They note that negative experiences (such as the stereotyping of Chinese students, and a lack of integration between students of different language backgrounds) can undermine this, and that the coronavirus pandemic has compounded latent hostility. Many South East Asian students faced backlash and harassment in light of the outbreak and were particularly alienated, or even physically abused, when wearing face masks; this has seriously undermined the UK’s reputation of providing safe and inclusive academic communities to prospective Chinese students.

Ignorance and contempt can often fuel these prejudices, and international students may encounter marginalisation and racism when using the languages and customs of their home countries (such as routinely wearing face masks if suffering from normal colds or hayfever). Indeed, a YouGov survey in February found that a troubling 26 per cent of British people felt ‘bothered’ when hearing foreign languages being spoken in public. As discussed further in the report I wrote for HEPI, A Languages Crisis?, engaging students with languages in schools and higher education, both within and outside the curriculum, is a valuable aspect of building intercultural awareness and empathy, even if students do not go on to reach a high level. For instance, if Chinese phrases and cultural activities are introduced in Early Years and Primary education, this can help to normalise inclusivity of and interactions with other languages and cultures, as well as encouraging more students to continue to take up further learning opportunities at secondary level.

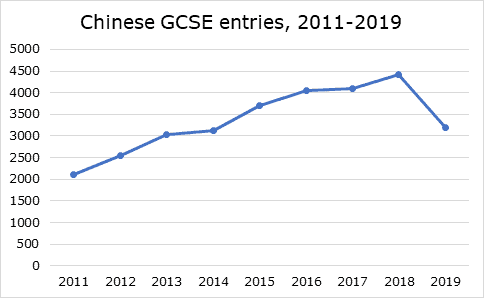

The number of students taking Chinese GCSE increased between 2014-2018, a rise which was aided by funded initiatives such as the Mandarin Excellence Programme. However, numbers fell in 2019 from 4,410 to 3,201 (27 per cent). But hese figures remain small compared to those for traditional European language choices (for instance, 130,831 took French GCSE in 2019). Certainly, it is currently harder for schools to source adequate resources and specialist teachers for Chinese, though secondary school Mandarin teachers are on the UK’s Shortage Occupations List and there are a growing number of teaching materials available online.

Increased contact with Chinese in education could therefore help to prevent China’s languages and customs being regarded as alien. Including these at Key Stages 3 and 4 could be one component of diversifying the education curriculum, challenging implicit assumptions that Western languages and histories are more worthy of academic focus. Having only experienced a little Mandarin myself in school, I asked a university friend about her experiences of Chinese GCSE:

Having compulsory Mandarin lessons, even for only a year, seemed to challenge students at my school in new ways – it helped to demystify Asian culture while presenting an entirely different linguistic challenge away from the Latin alphabet. The resources used even up to GCSE level were rooted in cultural education alongside language, leaving me hopeful that British children might be better exposed to and relish learning about cultures further afield from Europe. (Natasha Sharma, now studying Biochemistry)

Though substantial teaching time for students is required for students to progress onto exam qualifications, learning Chinese to any level provides an opportunity for a new challenge and can engage students who do not enjoy French, German and Spanish. For instance, Mandarin is grammatically very different to these traditional choices, as it does not conjugate verbs, use tenses, or have noun and adjective declensions and genders. Some students with dyslexia also find Mandarin a better fit, since it is character-based rather than alphabetic and can be taught with an oral rather than written emphasis.

What can higher education do?

Higher education also has an important role to play, not only in the context of academic subject provision but also through providing opportunities for language learning and experiences of different cultures to all students and staff.

A growing number of universities allow students from all disciplines to take a language option for course credits and at no extra cost, providing a structured and incentivised mode of learning – Chinese would be a useful asset to STEM students in particular. Others also offer free extracurricular learning, which can be valuable for students wishing to try a new language more informally and without the pressure of assessment. Certainly, using institutions’ existing academic resources to make both types of opportunity available would be beneficial in encouraging students to experience languages such as Chinese that they may not have been able to learn in school. Giving students subject-specific guidance on which languages could be useful for them to learn alongside their studies if they are undecided could encourage further uptake.

Promoting languages and intercultural engagement can also occur on campus, even in higher education institutions which do not offer Languages courses. For instance, Middlesex University launched a ‘Language and Culture Exchange’ scheme which pairs students so that they can provide mutual support in learning a language of their choice, making use of the existing linguistic diversity of the student body to encourage engagement with languages and friendships between students from different cultural backgrounds.

Comments

albert wright says:

This seems to be a very sensible proposal. (and therefore unlikely to make much headway?)

China is here to stay and likely to be a global force for at least another century.

If we really want to understand China we need more people that understand the languages of the country, Chinese and Mandarin.

If “know thy enemy” is true, the UK and the West need many more people who understand the Chinese language, Chinese culture and Chinese thinking.

Perhaps all the thousands that may soon come from Hong Kong might have a condition imposed that they all teach at least one British person Chinese in the first 2 years of UK residence?

Reply

Add comment