Why the answer to many questions this week will be 97%

How many people attend higher education has been a lively political issue for decades – the topic of many official white papers and green papers, ministerial and prime ministerial speeches as well as HEPI publications.

In general, politicians in power have tended to support expansion – for example:

- in the 1960s, the Douglas-Home Government accepted the Robbins report, parts of which were then implemented by the subsequent Wilson administration;

- in the 1970s, during her time as Secretary of State for Education and Science in Ted Heath’s Government, Margaret Thatcher published A Framework for Expansion;

- in the 1980s, Ken Baker’s delivered his famous expansionary speech at Lancaster University;

- in the 1990s, Tony Blair commited to ‘a target of 50 per cent of young adults going into higher education in the next century’; and

- in the 2010s, the Coalition Government removed student number caps and repeatedly claimed to be presiding over an increase in the proportion of people going to higher education (albeit by conveniently ignoring a big drop in the number of part-time students).

In recent weeks, the issue has flared up again, though in an opposite direction in England, where Gavin Williamson has pushed back against the old Blairite 50% goal. In Scotland, meanwhile, which has had a higher participation rate for higher education than England, discussions about ending the current status of EU students have led to the possibility of more places being made available for home students.

In conversations and debates about student numbers, HEPI’s publications have tended to be at the more expansionary, or optimistic, end of this debate. Since its first publication on demand, by Libby Aston which came out back in June 2003, to the most recent one, by Bahram Bekhradnia and Diana Beech from May 2018, HEPI has seen continuation of the post-war trend towards growth as likely to continue.

Even in recent weeks, as the virus has taken hold of British society, we have been reluctant to accept some of the pessimistic claims about drops in home (as opposed to international) student numbers. Declines could still happen, most notably if there were a significant second wave of the Coronavirus, but the published numbers to date show continued growth in the number of applicants: the number of 18-year olds is down this year but the application rate for UK 18-year olds is higher than ever before.

Killer facts

There is one good reason why we can be fairly certain that people who think higher education will shrivel in coming years are likely to be proved wrong.

The currency of policymaking is killer facts, as we remind all HEPI authors. These are those points, often numbers, which are so striking that lots of other things flow from them. Killer facts do not stand out because they are odd; they stand out because they clearly encapsulate some important basic underlying truth in a memorable way.

‘The Millennium generation of UK children may have the most educationally ambitious mothers ever, a new study suggests.’

For me, the outstanding killer fact above all others about UK higher education comes from the Millennium Cohort study, which is tracking the lives of thousands of babies born around the turn of the millennium. It is a serious piece of social science research in the great tradition of British Cohort Studies, which have taught us so much about the society in which we live – for example, much social science research on social mobility (or the lack thereof) in the UK depends on the 1946, 1958 and 1970 cohort studies.

Exactly a decade ago, in the second half of 2010, research on the Millennium Cohort found:

The Millennium generation of UK children may have the most educationally ambitious mothers ever, a new study suggests.

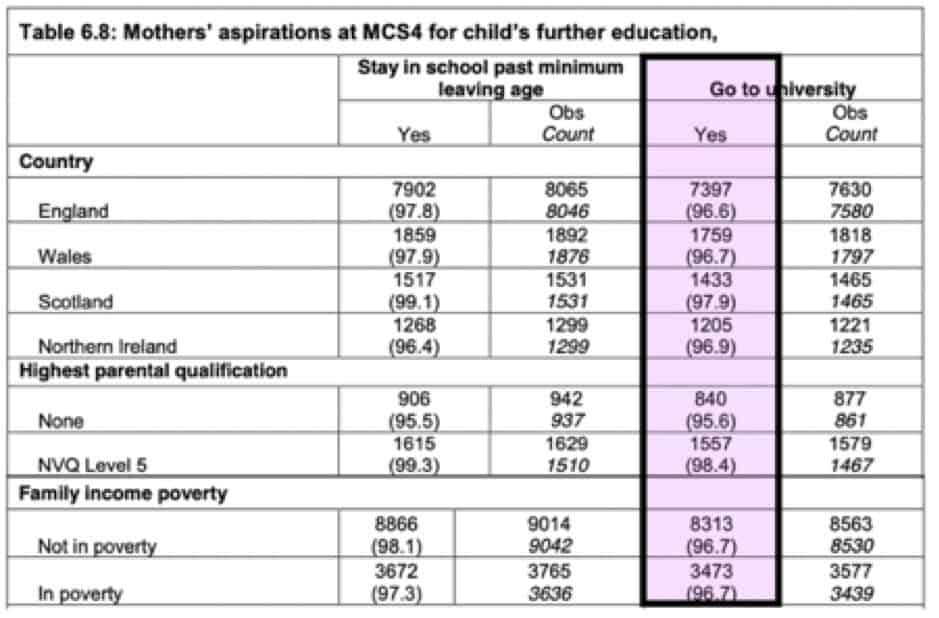

No less than 97 per cent of them want their children to go on to university, even though most did not have a higher education themselves, researchers at the Institute of Education, University of London, have found.

Today, roughly a third of young people in the UK progress from school to higher education. However, that proportion will be much higher in 10 years’ time if the mothers of children born in the first few years of the new century get their way, a survey of almost 14,000 families has shown.

People may express surprise that demand for higher education keeps on growing, that people with more disadvantaged backgrounds are often as keen as those from more advantaged backgrounds to access higher education and that people from parts of the country that have traditionally sent fewer people to higher education want improved access.

But even the quickest glance at the Millennium Cohort Study results should squash such views. They show the background of someone’s mother, the educational level of their mother or the part of the country in which they live all make very little difference to their ambition to attend university.

Many of those babies followed in the Millennium Cohort Study, who were born between 2000 and 2002, are now the typical age for applying to higher education. It is a decade since their families told us they planned to apply, so we should not be too surprised that they have now done so, even in the face of the disruption caused by pandemic.

A few years ago, I suggested that we might wish to consider setting a new target of 70% participation in higher education. My idea stemmed less from a belief that we should aim for such high participation (even though I do think that) and more from the clear fact that demand is likely to continue growing. When that happens, there are only three ways to respond: squash people’s ambitions about their own lives; expand provision in an ad hoc and unplanned way; or prepare for the coming wave.

Comments

albert wright says:

I am in no way surprised that mothers want the best for their children that more young people than ever want to go to University and that the number of under graduates and post graduates is likely to increase over the next 5 years.

Most self interested people who want someone else to pay for their education and those who supply the education want the bonanza to continue – why shouldn’t they.

Most people on furlough would rather remain there than go onto Universal Credit.

Just because expansion is likely to continue does not make it desirable for the rest of us who will not be beneficiaries.

I accept that from 1961 to 1970, I was the first of my family in the UK to go to a grammar school and then to the university in Manchester and get a degree which significantly improved my life chances. At that time I was one of the 5% in my age group to do so.

My argument is that it is both morally and economically wrong to expand tax payer funded University provision when the money could be used to improve early education and better housing for the less well off which would provide a better and fairer return on public investment.

Just because you are winning and have majority support for expansion, does not make it right.

Reply

Add comment