We have been running a selection of chapters from HEPI’s recent collection of essays Where next for university admissions? , which was edited and introduced by Rachel Hewitt, HEPI’s Director of Policy and Advocacy. On Friday we shared the chapter by Mary Curnock Cook, non-executive director across the education sector and former Chief Executive of UCAS, ‘Reflections 10 years on from the last PQA review‘.

This blog is the fourth in the series and is the chapter written by Rebecca Gaukroger, Director of Student Recruitment and Admissions at the University of Edinburgh. You can find Rebecca on Twitter @uniadmissionsuk.

How relevant to Scotland are proposed admissions reforms?

The calls for reform to the UK-wide admissions system have their roots firmly in England. The sharp-edged recruitment and admissions tactics that have developed as a consequence of the quasi-market conditions in England are largely unseen in Scotland.

Relatively few Scots apply to university prior to receiving any SQA Higher grades. Many offers made to Scots are unconditional, on the basis of Higher grades achieved the summer prior to application.* Even conditional offers are generally informed by qualifications achieved in the previous academic year. So, applicants are able to make informed application choices on the basis of their results, and universities make offers on the basis of achieved, rather than predicted, grades.

Where this pattern is changing, it is not among the school leaver cohort, but among students pursuing higher education qualifications in colleges. A growing number of these students are on formal articulation routes from college to university or have Associate Student status at the university they will ultimately attend. In these circumstances, and unless a student decides to change their plans, the UCAS process is a formality.

Scottish Clearing remains quiet, with few places advertised, and very few Scots choosing to trade a main scheme Firm choice for a place elsewhere come August. Around 500 Scots were placed at a new choice having ‘self-released’ from the main scheme into Clearing in 2020 (1.3 per cent of all accepted Scotland-domiciled applicants against 4.7 per cent of all England-domiciled).

Most obviously, student number controls have kept a lid on the participation rate in Scotland and meant, even with the ‘demographic dip’ in 18-year olds, demand has broadly exceeded supply. Pre-Brexit, EU students were treated on the same basis as Scots, competed with Scots for limited funded places and like Scots had no tuition fees to pay. In 2020, 14 per cent of all applications to Scottish universities were from the EU; twice the rate in the rest of the UK.

The interests of applicants in Scotland are distinct from 18-year old applicants in England. From the perspective of most Scottish applicants to Scottish universities – approximately 95 per cent of Scots who go to university do so in Scotland – a greater concern is not the opacity of the market, or the machinations of the UCAS process, but straightforwardly how to get in to university at all.

Widening access through admissions

The focus across the Scottish education system – and the Government – has been squarely on closing the attainment gap and widening access to higher education.

In May 2016, Scotland’s First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, announced:

A child born today in one of our most deprived communities must, by the time they leave school, have the same chance of getting to university as a child of the same ability from one of the most well off parts of our country. This is a fundamental part of what I mean by a fair and equal society.

This pledge has driven university access and admissions policy in Scotland in the years since, and there is no sense it will abate in the near future.

The Commission on Widening Access (COWA)’s Blueprint for Fairness, adopted in full by Scottish Government, provides the framework to realise the First Minister’s ambition.

The importance of progress against the COWA milestones and targets is now embraced almost universally by university managers, if not the academic higher education policy community. Key among these milestones is participation by students from the most deprived communities according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD), representing the lowest quintile of the measure: SIMD20 or SIMD Q1.

Scottish universities have agreed a common approach to contextual admissions, with clear blue water between ‘minimum entry requirements’ for widening access applicants and ‘standard entry requirements’ for others. Universities have pledged to guarantee offers to care experienced applicants.

The number of articulation routes between college and university has grown steadily, with every university in Scotland now offering access on this basis. Graduate Apprenticeship opportunities are increasing, too, though the impact of COVID-19 has temporarily reduced opportunities.

These changes to progression routes, the mainstreaming of guaranteed and widening access offers, enhanced funding for care experienced and estranged students – all make the PQA reforms largely irrelevant to widening participation in Scotland. The interests of applicants who historically have been poorly served by university admissions are already to the fore.

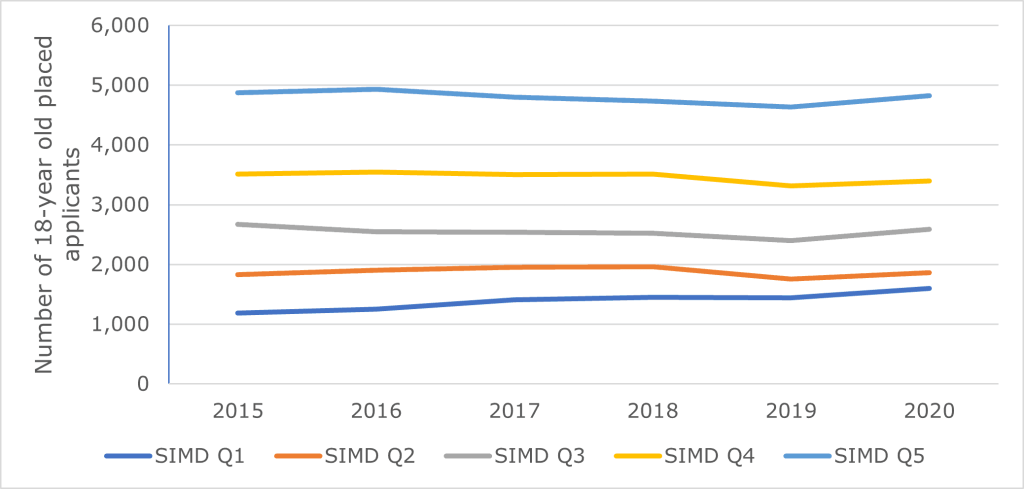

The intake of SIMD20 students has increased markedly. Between 2015 and 2020, the number of 18-year olds from SIMD20 areas entering Scottish universities increased by nearly 26 per cent.

However, in a closed system with student number controls, the consequences of the focus on widening access have not been universally welcomed. Despite contextual admissions policies that recognise other under-represented groups, entry to Scottish universities has remained highly stratified by SIMD.

Without more places, equalising access between the least and most deprived areas is likely to suppress participation by those in between. More places would obviously come at a cost to the Government.

There is a chance a solution will come from an unlikely source: Brexit. In 2020, 4,110 EU students were accepted onto undergraduate courses at Scottish universities. If the number of funded places previously filled by EU students is retained in the system post-Brexit there are significant opportunities to increase the participation rate in Scotland, and to equalise access across the board.

Offer rates would be likely to increase, giving more Scottish applicants more choice and more power in the system.

It could also give the system the capacity to take collaboration to another level, particularly in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subjects that have been sustained at undergraduate level in many Scottish universities by EU students, with limited unmet demand from Scotland. Established partnerships with colleges and industry could be seized upon to develop a Scottish STEM pipeline – which would surely be welcomed by the Government, in the context of moves to make tertiary education in Scotland more coherent and integrated.

The Scottish Funding Council’s Review of Coherent Provision and Sustainability, commissioned by the Scottish Government in June 2020, presents an opportunity radically to change the delivery and experience of post-16 education in Scotland. Relationships between schools, colleges and higher education institutions are already strengthening through the growth of articulation routes and the six City Region Deals in Scotland. The outcomes of the Review could deliver much more.

A more integrated system will need to balance student choice, institutional distinctiveness and autonomy on the one hand, with strong regional partnerships and seamless and certain transitions on the other.

This means portable qualifications and credit, and requires a significant enhancement of information, advice and guidance to enable people to navigate a complex landscape of qualifications, providers and funding.

The development of bridges and pathways into and through tertiary education is unlikely to shake the dominant demand for on-campus, full-time study. The proportion of higher education students in Scotland studying on a full-time basis continues to increase. One-in-three (30 per cent) of undergraduates at Scotland’s universities are from outside Scotland, applying with a range of qualifications. Some gain advanced entry, but most choose to study for the full four or five years of an undergraduate degree.

This increasing of diversity of qualifications and routes may cause universities to think more deeply about their admissions entry requirements and approaches to selection. The experience of the 2020 and 2021 entry cycles demonstrates the limitations of an admissions system dependant on applicants clearing a qualification hurdle, which in many circumstances operates as a crude proxy for ability. The particular skills and knowledge a candidate possesses, which may be evidenced through a variety of qualifications and experiences, will need to be better understood and valued in future. In the face of pressure on resources and calls for more automation of administrative processes, more nuanced and sensitive judgments may need to be made in admissions decision-making.

*UCAS has excluded applicants from Scotland from its analysis of unconditional offer-making, because the basis of unconditional offer-making to Scots is different from the now dominant practice in England. Frustratingly, though, it means no sector-level data are available on the conditional / unconditional offer-making split in Scotland.

**Changes to postgraduate Initial Teacher Education (ITE) admissions in England have meant that applications to postgraduate ITE programmes in Scotland are processed via the UCAS undergraduate scheme. An unfortunate consequence is that published UCAS undergraduate admissions statistics for Scotland includes these postgraduate courses. Filtering reports by age excludes these courses, but also excludes mature students and adult returners to undergraduate courses and understates undergraduate entry.

It is very helpful to have this information. I had not realised how different things are in Scotland, the size of the EU student population at Scottish Universities and the very low numbers from England.

When both England and Scotland were members of the EU, I could never understand why English students did not get free places at Scottish Universities and still do not understand why Scotland would want to pay to educate students from other EU countries (unless there was a reciprocal offer from the EU for Scottish students studying in EU countries?)

Another question is “Do students from Scotland who go to English Universities have the same right to student loans as English students?”

Finally, are there any studies that have investigated which system, English or Scottish, is better for students, based on clear criteria?