Why highly selective universities need to demystify admissions for student applicants

This blog was kindly contributed by Lee Elliot Major and Kieran Tompkins. Lee is Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter and Kieran is a 2021 Business and Management graduate at the University of Exeter. You can find Lee on Twitter @Lem_Exeter.

For the pandemic generation of A-level students, this could be the perfect storm. Inflated A-level grades in 2021 will produce unprecedented numbers of pupils with the grades required for even the most demanding degree courses. With declining job prospects, rising student numbers and potential caps on degree places, the admissions landscape promises to be a far tougher environment for student applicants. The race for places at highly selective universities is set to intensify.

Spare a thought in particular for poorer pupils who have suffered the largest learning losses during almost a 18 months of COVID school closures and disruptions. To make matters worse, unconscious bias in teacher assessments will likely benefit middle class pupils. Face-to-face university outreach work has had to be abandoned. There is a genuine worry that social mobility efforts will be put back years.

The post-pandemic era makes it even more important that universities do all they can to communicate clearly to they are welcome places for students from all backgrounds, to debunk unhelpful myths and to make their admissions processes as clear and simple as possible. Yet new analysis lays bare some of the misperceptions and complexities in elite higher education that make it so hard to navigate and often so alienating for many students. It suggests we need to do much more to make elite universities truly transparent and inclusive institutions.

State school intakes

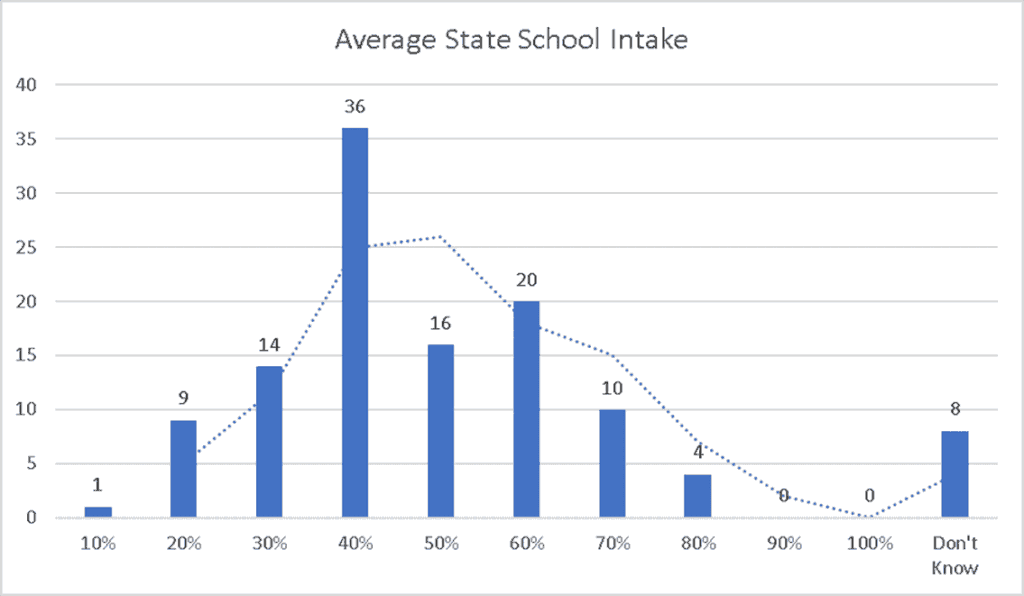

As part of a dissertation research project at the University of Exeter, 118 current university students were surveyed at Russell Group universities. These 24 institutions offer degree courses demanding the highest A-level grades and have seen little change in enrolment gaps between private and state school students over the last decade. Among a series questions the students were asked to gauge the average proportion of state and private school students at Russell Group universities. The results are presented in Figure 1 below.

The average response estimated that state school students make up 46% of intakes at Russell Group universities. This is a significant underestimate of the actual proportion which is 77.4% of intakes. Indeed, 78% of the survey respondents attended state schools reflecting the overall make up of student bodies. (State schools make up 93% of all schools).

many students perceive universities as more privileged places than they are in reality – even when they themselves are studying at the institutions.

Overall, the results point to a widespread misperception among Russell Group students that private school students make up the majority of students. In reality this is not the case at any university. These findings are indicative given the small numbers surveyed, but they resonate with previous results. Sutton Trust work, for example, found that over 60% of teachers underestimate the percentage of students from state schools on undergraduate courses at Oxbridge. The latest findings suggest that many students perceive universities as more privileged places than they are in reality – even when they themselves are studying at the institutions.

Contextual admissions

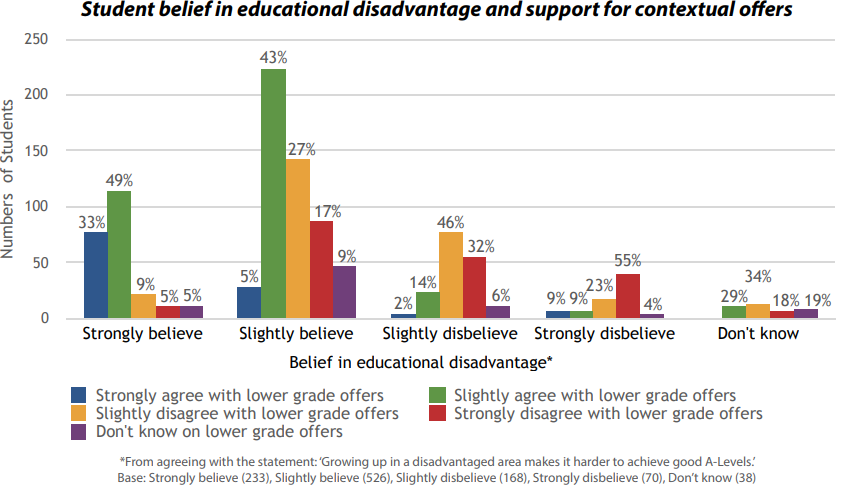

The research also reviewed admissions criteria at Russell Group universities, in particular documenting the use of contextual admissions. Contextualised offers occur when a university takes into consideration an applicant’s personal circumstances by for example reducing the A-Level grades a student requires from a disadvantaged area. In a parallel survey as part of this research, heads of widening participation rated this approach as one of the most effective tools in helping to enrol more students from poorer backgrounds.

Few topics in higher education generate as much interest and debate. Previous HEPI research concluded that while most students support contextual admissions, there is considerable ignorance about them. It has also been suggested that greater consistency in how contextual data is used might enable greater certainty among applicants. University regulators have urged more ambitious use of contextual admissions, yet the Minister of for Universities in England has appeared sceptical, arguing that ‘we don’t help disadvantaged students by levelling down – we help by levelling up’. It is unsurprising that survey respondents from universities spoke of a need to preserve a ‘safe space’ to work on contextual methods and avoid charges of unequal treatment of applicants.

Figure 2 presents an analysis of information taken from Russell Group university websites during the 2020-21 academic year.

[table id=13 /]

Figure 2: Analysis of Russell Group University Contextualised Admissions Indicators.

The chart highlights the huge complexity in the practice of contextualised admissions. The 24 Russell Group universities use 18 different factors in their decision-making. These include:

No two universities use the same combination of information.

The table shows just how much institutions could benefit from greater use of individual-indicators, in particular eligibility for free school meals. A series of reports have shown this is the best available marker for identifying disadvantage. Universities are currently having to rely on ‘proxy’ postcode measures that are not as effective at identifying low-income students. Moves by the admissions service, UCAS, for the first time to provide universities with systematic data on individual free school meals could be a game-changer.

The table also reveals just how baffling it must be for outside applicants who may qualify for these schemes. Greater consistency and transparency are needed across universities to provide clarity to students. A more common approach would have the added benefit of helping researchers generate much needed evidence on the effectiveness of this approach.

Conclusions

For many A-level students securing a place at a Russell Group university, this year will transform their lives, opening up a future of opportunity. But this research suggests that much more work is needed to demystify these institutions for applicants who may be put off applying because they think they may not fit in or are not aware of the contextualised admissions they may benefit from. In the post-pandemic era of admissions, universities will have to up their game.

Comments

Add comment