This blog was contributed by Chris Millward, Director for Fair Access and Participation at the Office for Students.

Next month I will make my final trip to meet staff and students as Director for Fair Access and Participation in England. These visits, punctuated of course by the pandemic, have crossed the country from Newcastle to Exeter and Liverpool to Norwich, and included all types of universities and colleges: from the London School of Economics to the London School of Management Education, New College Durham to the New College of the Humanities and New College Oxford, and the Royal Agricultural University to the Royal College of Music. Each one has been unique, demonstrating that our universities and colleges are more diverse than generally portrayed and perceived.

Student voices

Notwithstanding this diversity, a common feature has been a roundtable discussion with students supported through the institution’s access and participation plan, shepherded by a senior manager who then cautiously retreats from the room. These students are usually the first in their family to go university and from communities and schools where this is the exception, they sometimes have experience of care or have been caring for others, they have had specific impairments that affect their studies or have entered university later in life.

If you work with students like these, you will know how clearly they describe the path they have taken: the moment they knew they wanted to go to university; the barriers in the way; who and what made the difference; how it feels to be there; what they want to do next. They can articulate — in a way those who have progressed inevitably cannot — the achievement of getting into university, its intellectual and personal impact, and what it makes possible. Also, how tough it has been to get there, the persistence and resilience it continues to demand from them, and how unfair it can feel when others have had — and will have — more choices and opportunities in relation to their routes through education and work. These students are more likely to talk about expectations — the realistic perceptions among their family, friends and community about going to university — than aspirations.

I often remind the students in these meetings what they give back to their universities. Students learn from each other and staff learn from students, so a healthy and vibrant educational environment brings different perspectives and life experiences together. Universities tend to different degrees to be proud of their research standing, their global profile, their estates and their links with industry and public services. But they are all, in my experience, exceptionally proud of the students who have travelled furthest to reach them and want to show how the university has accelerated their journey. This means that students can be the most powerful voice for access and participation, showing the next generation that people from their schools and communities can succeed, whilst raising the ambitions of senior leadership and governors, and holding them to account.

Fair equality of opportunity

In addition to enlightening universities, student perspectives like these can illuminate the conceptual questions running through the sector’s work on access and participation, for example what we mean by promoting equality of opportunity —the statutory basis for universities’ access and participation plans— or fair access.

These questions were important when I started this job because I saw more concern with promoting opportunity in relation to access by encouraging applications (‘spray and pray’, as a teacher described it to me) than equality of opportunity by ensuring that they lead to a more equal pattern of admissions, success on course and graduate employment. Fair equality of opportunity, as I highlighted at the consultation events we held on the regulatory reforms we made in in 2018, requires not just that processes are formally open and meritocratic, but that everyone has a fair chance to succeed.

Students’ own stories demonstrate vividly the extent to which this is not the case across our educational system, persisting well beyond school. They show how difficult it is to bridge the fabled gap between talent and opportunity, and that outcomes matter to students and their families – entering the course of their choice, having a positive experience at university, achieving good grades and getting a fulfilling graduate job.

The promotion of equality of opportunity is only meaningful if it improves outcomes: there is no point to it otherwise, let alone spending more than half a billion pounds on it each year as we do in English higher education today. Students and their families quite rightly expect this to be the test for our work. That is what they mean by fair.

Here are two examples of the scale of this challenge.

School attainment and university access

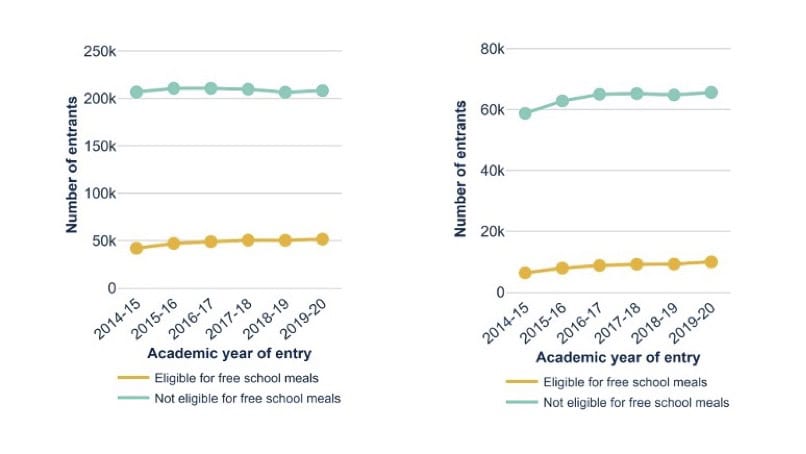

Figure 1 below shows the progress made during the last decade on reducing the gap between students entering higher education who have been eligible for free school meals and those who have not, which is also the measure used to understand the attainment gap in schools. It shows increasing levels of participation among students eligible for free school meals, but the gap changing little, indeed increasing in the high tariff universities.

Figure 1 – The access gap between students eligible and not eligible for free school meals overall (left) and in high tariff universities (right)

Source: OfS analysis of NPD, HESA and ILR data

We know the gap is particularly large for students who have been eligible for free school meals in post-industrial towns and parts of cities across the north and midlands, and in coastal towns. More than 90% of the lowest higher education participation quintile have been eligible for free school meals or come from these places. These are students the Education Select Committee has identified as ‘left behind’.

Why did this happen, despite the substantial investment by universities to promote fair access during this period? The answer can be found in the progress made on reducing the attainment gap in schools and the close relationship between school grades and university admissions.

Figure 2 – Progress on reducing the disadvantage gap in schools

Source: Education Policy Institute 2020 – Annual Report

Figure 2 above shows that progress on the attainment gap between the most and least advantaged students moved into reverse towards the end of the last decade. These results also precede the pandemic, which is considered to have harmed the learning of disadvantaged pupils more than others, and it excludes private schools, which had the highest increase in grading this year.

There is a particularly strong link between social background, school attainment and university admissions in England, so it should be no surprise to see a relationship between the two charts. If, though, universities are to improve equality of opportunity — and indeed avoid it worsening due to lost learning — they will need to take positive action during the coming years.

Universities make an important contribution to raising attainment in schools through their training of teachers, their subject expertise and their involvement in school governance. The placement of staff from universities and outreach partnerships in schools and colleges has proved to be particularly effective. A survey last year suggested that local communities identify support for schools among the most valuable contributions universities can make to their localitiesand this has become more important due to the pandemic. This will, though, take time and it will be the investment in and efforts made by schools, rather than universities, that will ultimately determine their recovery from lost learning during the coming years.

In the meantime, universities can recognise that the grades of many disadvantaged students demonstrate that they have travelled further and offer greater potential to succeed in higher education. Universities have independence in relation to their admissions precisely so they can make nuanced individualised judgements of this kind. Many are now doing so, building on the case we made in OfS to re-think merit when we were negotiating access and participation plans in 2019.

This is quite different to the US approach to affirmative action or crafting a class, but it recognises that, given the patterns above, students who are the first in their family to apply to higher education, or come from schools and neighbourhoods with low levels of higher education participation, are unlikely to demonstrate their full potential through exam results alone.

This is not an easy route to equality of opportunity. The students I meet in universities identify the importance of a sustained package of support, including academically stretching work before admission and an academic offer that reflects their potential, as well as financial support to meet the cost of living during their studies.

Alongside this, universities can give greater priority to routes other than young, full-time, full-degree entry within their access and participation strategies, enabling more people to enter higher education when they are older, and thereby diminishing the influence of attainment gaps in school. This must not, though, be a bolt-on to existing provision — it requires specific consideration of the needs of employers and adult learners, including more flexible delivery to meet demand, careful consideration of how to recognise prior and ongoing learning in the workplace, and measures to develop core competencies for learners who may not have studied subjects like maths and English for some time, indeed may have failed when they were young.

We have learned a lot about flexible delivery through the shift to blended and online learning during the pandemic and there will be important findings from the short course trial we are running in OfS. There is also extensive experience of professional training at all levels of English higher education and a growing body of learning from degree apprenticeships. This is again, though, not an easy win. It requires a clear mission, sustained investment, robust evaluation and a commitment to put learning into practice.

Geographical inequality and graduate jobs

People from quite different backgrounds and perspectives are concerned about inequalities between different parts of the country. In education, we see such inequalities demonstrated in GCSE and A-level results, which show a growing gap between the students achieving the highest grades in London and the south east compared with other parts of the country, as in Figure 3 below. This then influences university entry patterns, as discussed above.

Figure 3 – Regional distribution of 2021 GCSE and A-level results

Source: Ofqual 2021, Infographic – A-level results 2021 and GCSE results 2021

These gaps in educational attainment and progression are compounded by the opportunities available to graduates in different parts of the country. Figure 4 below shows that most graduates in the north of England live in areas where there are the lowest proportions of well-paid graduate jobs and there are similar patterns in many coastal towns. The opportunities for highly skilled work are more evenly spread than those for the highest earnings, with some cities across the north, midlands and south-west performing better than some of the areas around London, but there are still weaker opportunities in rural and coastal areas, as well as towns across all parts of England.

Figure 4 – Proportion of graduates earning above £24,000 or in further study after 3 years (left) or in highly skilled jobs or further study after 15 months (right)

Source: OfS 2021, A geography of employment and earnings

People who study locally are more likely to be from disadvantaged backgroundsand to seek employment in their home region. This means that the geographical disparities shown above have a profound effect on the employment prospects of the most disadvantaged students, with those entering higher education outside of London, the south east and some major cities affected most.

One answer to this might be to encourage graduates living in these places to move away from their local area to study and work – after all, the common conception of higher education and social mobility involves moving away to university and then an elite job. If, though, the most educated people leave an area to gain good employment, this can only compound the challenge for future generations. Highly skilled people are needed to run public services, stimulate enterprise and attract investment, even before you consider the desirability of being able to choose where you live and work, and to live near your family and friends if you want to.

Another approach might be to encourage people in areas where there are lower school grades and graduate earnings not to go to university at all, for example by completing their studies at lower levels and going directly into work. There are powerful arguments for spending longer on the journey to the highest levels of education — progressing through further education, whilst in work and later in life, and in a format and timescale that better reflects different needs. But it would be profoundly unfair to prevent people from having the opportunity to benefit from higher education due to the circumstances in which they have grown up. It would also be unlikely to succeed, given increasing levels of demand for universities in this country and beyond and the extent to which this has influenced policy on the size and shape of English higher education sector for much of the last century.

I am pleased that discussions about social mobility have shifted from enabling people to leave their local area to improving their prospects if they want to stay. But this must not lead to a new binary divide between mobile academic routes for those who get the right grades in school and local technical routes for others. We need universities and colleges to work together to create pathways through academic, professional and technical education at all levels, and to provide choices for students, locally and nationally. Limiting these choices would be regressive and divisive. I hope, then, that we will hear less about national policies to reduce access during the coming year and more about local strategies that will capitalise on the talents of all our graduates, whatever their background and wherever they live.

The trouble with articles about “Fair equality of opportunity means a fair chance to succeed” is that many of the words (fair, equality, opportunity, succeed) mean different things to different people. The meaning they have to people considered to be from disadvantaged areas also differs from those who are outside the disadvantaged areas.

The author exemplifies this by noting different ways the objectives can be achieved.

Most people would agree that “Life is unfair”, that every area has a mix of winners and losers – even disadvantaged areas have people living there who have degrees and who earn relatively more money – but that the percentage of such people is low compared with elsewhere – hence the term disadvantaged area.

This becomes the “Catch 22” – bizarrely, to benefit those from a disadvantaged area means that the area has to become less disadvantaged.

But the current, geographic, disadvantaged areas will remain so until external forces intervene to bring the area a University of its own (or a local branch of a University elsewhere) and “artificial” graduate jobs by setting up, for example, a part of the Treasury near Darlington (which will not be sustainable until a local University can deliver the necessary graduates).

The challenge will be permanent. Local prosperity will be slow to improve organically but to speed up the process raises issues of “personal freedom of choice” that might need to prevent the new graduates from leaving the area – like forcing new GP doctors to go to the area after graduation – so the newly “successful” become the new disadvantaged in situ!?