Policy divergence: Changes in student funding systems across the UK since 2002/03

*** Sign up now for our webinar with UCAS Chief Executive Clare Marchant, taking place at 11am on Monday 14th August. ***

- This blog was kindly authored for the HEPI 20th Anniversary Collection by Professor Claire Callender, Professor of Higher Education Studies at University College London.

- In August, we are running chapters from the Anniversary Collection as a series of blogs. This piece is the seventh chapter from that collection.

Central to the expansion of higher education is how it is funded and who pays. This debate predates HEPI’s launch 20 years ago and continues today. At stake are equal access and the sector’s financial sustainability and quality. These are driven by ideological, political and economic decisions about the amount and balance of financial contributions from individual students, graduates and their families, and from the state and taxpayers.

The trend overall, starting in the 1990s but intensifying in the last decade, has been to shift more of the costs of higher education away from the state onto the shoulders of individuals. This reflects other policy developments which relocate responsibility for welfare and wellbeing from the state to the individual through ‘financialisation’.1 It has been achieved in higher education through the introduction and expansion of tuition fees and student loans which call upon the ideological mantra of ‘who benefits, pays’. Students and graduates are deemed by policymakers as key beneficiaries of higher education because of the financial returns most reap from their higher education, and which render the repayment of tuition fees and maintenance loans affordable.

However, a distinctive feature of the UK’s student funding system is the differences between its four parts – England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (NI) – in their policies, emphasis on public and private financial contributions and, consequently, in their mix of student financial support. The funding policy divergence, resulting from political devolution, has become more pronounced since HEPI’s creation in 2002 with varying implications for the four higher education systems, their students and graduates.

This chapter charts key changes in student funding provision since 2002 with an emphasis on first-time undergraduate fulltime students. It discusses significant differences between the UK jurisdictions and by students’ domiciles and their mode of study.

Student funding, 1998-2005

From 1998, all first-time full-time undergraduates were subject to means-tested tuition fees of £1,000 per year paid upfront.2 These students were also eligible for maintenance loans, first introduced in 1990 and subsequently partially meanstested; these were operated through the Student Loans Company (SLC), a quasi-government agency responsible for administering student financial support throughout the UK.

This system remained in place in England, Wales and NI until 2005, with Scotland using its devolved powers to abolish tuition fees for Scottish-domiciled students studying in Scotland in 2000. The following year, Scotland reintroduced national means-tested grants for young locally domiciled students of up to £2,000 to augment existing maintenance loans. It also established a one-off contribution of £2,000 (the ‘graduate endowment’) repaid post-graduation.

Student funding, 2006 to 2011

Following the Labour Government’s 2003 White Paper, The Future of Higher Education, in 2006 full-time undergraduate tuition fees were raised and capped to a maximum of £3,000 per annum in England and Northern Ireland.3 All full-time undergraduates domiciled in England or Northern Ireland, irrespective of their socio-economic background, paid fees wherever they studied in the UK. All qualified for newly formulated income-contingent loans (ICL) covering all their tuition and some living costs.4 These loans removed up-front cost barriers to higher education whereby higher education was free at the point of entry for all undergraduates, making the tuition fee rises more politically and socially acceptable.

The repayments of income-contingent maintenance and fee loans in the UK – which continue today – are based on graduates’ income and ability to pay. They are designed to protect graduates from excessive loan repayments, financial hardship or defaulting on repayments – unlike traditional ‘mortgage style’ student loans, the commonest model worldwide. Graduates start repaying their loans once their post-graduation income reaches the government-set repayment threshold. They pay 9% of their income above the threshold until they have repaid their loans in full (including interest accrued), with any outstanding debt written off after a set number of years. Repayments are automatically deducted from graduates’ gross wages via the tax system.

The Westminster government launched other financial support for low-income full-time students because of concerns that the tuition fee increase would deter higher education participation. They re-introduced means-tested maintenance grants of up to £2,765 previously abolished in 1998, and in England, established cash bursaries or fee waivers funded from universities’ additional tuition fee income. Consequently, low-income students qualified for grants, loans, and bursaries toward their living costs, while their more affluent peers were only eligible for loans.

Policy changes in England provoke different responses in each of the other three regions of the UK, at different times, for a combination of practical, financial and political reasons which vary between jurisdictions. Both Welsh and Scottish administrations used their student funding policies to demonstrate the apparent advantages of devolution. In Wales, tuition fee arrangements remained unchanged until 2007/08 when fees of £3,000, underwritten by income-contingent loans, were launched alongside a non-means-tested fee grant of £1,845 for all Welsh students studying in Wales, reducing de facto students’ fee liability. But this fee grant was subsequently abolished in 2010/11. However, means-tested maintenance grants, first re-introduced in 2002, were increased to £5,000 in 2010, making the grant considerably higher than elsewhere in the UK.

By contrast, Scotland took a different path in 2007. It abolished the graduate endowment with the Scottish government paying the tuition fees of Scottish and EU students studying at Scottish universities. Scotland’s free tuition, which continues today, makes it unique in the UK. It exemplifies the principles of universalism rather than of the marketisation which characterises the English higher education system. And it frames higher education as a public good rather than a private good, unlike in England, with access slated as based on ‘the ability to learn rather than the ability to pay’.5 However, as discussed below, constraints on the public funds available have an impact on the number of ‘tuition free’ university places Scottish universities can offer.

Student funding 2012 – present day

England

In England, the Coalition Government enacted further reforms in 2012 following the 2011 White Paper, Students at the Heart of the System, prompting further marketisation of higher education, with funding following the student to promote greater student choice and provider competition.6 The Westminster Government initially raised the cap on fulltime undergraduate tuition fees to £9,000, repaid by incomecontingent loans, and then increased this marginally in 2017 to £9,250. Simultaneously, it withdrew most of its direct funding for teaching to higher education institutions, making them far more reliant on tuition fee income and, over time, radically reshaping the pattern, scale and sources of funding. In 2020/21, 55% of English HEIs’ total income came from tuition fees and 10% directly from government grants, compared with 32% and 33% respectively a decade earlier.7 These policy changes have allowed Westminster governments to rely increasingly on tuition fees to fund English higher education and cut direct funding, more so than in other UK jurisdictions. The upfront balance of private and public financial contributions has shifted dramatically with tuition fees and loans shouldered by individuals replacing collective direct public funding.

But since 2017, fee levels have been frozen and latterly inflation has eroded their real term value to £6,585 (in 2012 prices) to institutions’ cost, thus, bringing into question the financial sustainability of this particular English funding model. 8

In 2016, the Conservative Government abolished undergraduate maintenance grants, rendering England unique within the UK in terms of grant provision. It replaced grants with larger, but stringently mean-tested, maintenance loans. But it left untouched the parental earnings threshold for the receipt of maximum loans, which has been frozen since 2008. Thus, increasing proportions of students from middle-to-lower income backgrounds receive smaller maintenance loans, while the poorest graduate with the largest student loan debt. Furthermore, recently maintenance loans (ranging from £4,651 to £13,200 in 2023) have not risen in line with the true measure of inflation, contributing to a students’ cost-of-living crisis.9

Additionally in 2012, the Government, for the first time, introduced comprehensive financial support for part-time English undergraduates, mirroring full-time provision with tuition fees capped at £6,750 in 2012, raising to £6,935 in 2017, and tuition and maintenance income-contingent loans.10 However, the eligibility criteria for these loans tend to disadvantage part-time students, leading to sharp declines in part-time enrolments in England after 2012. In contrast, after an initial blip, full-time numbers continued to rise, aided by the lifting of the cap on student numbers in 2017.11

The overall structure of the income-contingent loan repayment arrangements introduced in 2006 remained in 2012 and are still in place today throughout the UK. What now varies between UK jurisdictions, and has changed since 2006 for English undergraduates, is: the ICL repayment threshold (rising from £15,000 in 2006 to £21,000 in 2012 and £25,000 in 2018 to £27,295 by 2022 and back down to £25,000 in 2023); the debt write-off period (lengthening from 25 years in 2006 to 30 in 2012 and 40 in 2023); and interest rates (increasing from RPI to income-contingent rates of up to RPI+3% in 2012, and falling back to RPI in 2023).

These loan repayment modifications aim to cut public expenditure on higher education. Specifically, governments have sought to reduce the level of income-contingent loan subsidy. In 2020/21, for every £1 the Westminster government loaned English-domiciled undergraduates, it could expect to receive back 56p – a subsidy of 44%. Only 20% of full-time undergraduates starting university in 2021/22 are expected to repay their loan in full before the government writes off their debt. But the Government hopes that, following its 2023 reforms, this will rise to 55% for the 2023/24 cohort as more lower-to-middle income graduates will enter repayment, repay more for longer and be in debt to the SLC for most of their working lives.12

Wales

In 2012, the maximum tuition fee that institutions in Wales could charge was raised to £9,000 and continues today. However, students ordinarily resident in Wales only paid fees of £3,465 (the figure that had applied in England) and were eligible for income-contingent loans to cover all their tuition fees. Welsh students studying elsewhere in the UK and facing fees of £9,000 also qualified for an additional non-means tested tuition fee grant up to a maximum of £5,535 to cover the higher fees. Consequently, Welsh undergraduates studying elsewhere in the UK paid lower fees than their English peers because of this dedicated fee grant covering all fee costs over £3,465 which effectively capped fees.

This fee grant was replaced by others following the Diamond Review which invoked ‘progressive universalism’ to guide its reforms.77 Since 2018, all full-time Welsh undergraduates have been entitled to maintenance support totalling a minimum of £9,950 per year in 2023/24.13 This aid consists of a mixture of non-repayable means-tested grants and maintenance loans, with the balance between grants and loans determined by students’ household income.14 Thus low-income students receive nearly all their living support as a grant, and highincome students as loans who will borrow and owe much more than their less affluent peers. Part-time students are similarly eligible for tuition fee income-contingent loans and maintenance grants and loans.15 Wales’s shift to higher maintenance grants is unique in the UK, as is its distinctive approach to combining means-tested and non-means-tested benefits and targeting of grants. Both are indicative of Wales’s emphasis on financial support for living costs.

Scotland

Following the 2012 reforms in England, Scotland kept free tuition for Scots (and EU citizens) studying in Scotland, increased loans to £9,000 for Scottish students studying elsewhere in the UK and increased the cap on tuition fees for students from the rest of the UK to match the £9,000 in England.17 Scotland has prioritised free tuition at the expense of generous and targeted financial support for living costs.18 In 2013, the Government cut the maximum means-tested maintenance grants for both young and mature students, then increased and subsequently froze them. By 2023/24, undergraduates qualified for grants (bursaries) up to £2,000, depending on their household income and age – far less generous than grants in Wales or Northern Ireland. The reduced grant income is off-set by higher partially meanstested maintenance loans, ranging from £6,000 to £8,000 by 2023, with the poorest students receiving both the largest grant aid and loans.19 But the distribution of student loan debt is regressive with the poorest graduating with the largest student loan debt, as they do in England. In March 2023, the Scottish Government announced a £900 uplift of bursary and loan packages for the following academic year.

Another ‘cost’ of Scotland’s free tuition is the Government’s cap on Scottish student numbers, potentially to the detriment of widening participation. No such limits exist for students from outside Scotland, leading some to suggest that institutions in Scotland recruit such students to bolster their financial position at the expense of local students.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland’s response to the 2012 English reforms was different to that in Wales and Scotland, illustrating yet another approach to the balance of public and private contribution to higher education costs. In 2012, the Executive capped tuition fees at £3,465 for Northern Irish students studying in Northern Ireland, raising the cap to £4,710 by 2023/24 – far lower fees than England or Wales. Northern Ireland, therefore, has retained more of a dual funding system than the rest of the UK, with substantial funding coming from both tuition fees and directly from public grants. In 2012, the maximum tuition fee loan was raised to £9,000 for Northern Irish students studying elsewhere in the UK while students from the rest of the UK paid fees of up to £9,000 to study in Northern Ireland. Maintenance grants and loans for full-time students domiciled in Northern Ireland were available for study anywhere in the UK. By 2023/24, the maximum grant was £3,475 and maximum loan £6,766, which was increased for the first time since 2009.20

Discussion

Over the part 20 years, since HEPI’s launch, the pattern, scale and sources of higher education institutions’ funding has been reshaped radically across the UK jurisdictions. Differences in the headline student funding policies have become more marked. These could not have been formulated and effected without the political, economic and ideological shifts that drove and shaped the introduction of income-contingent loans and tuition fees. But there are trade-offs. Scotland stands out for its free tuition for Scottish students. But this is at the cost of grant aid for low-income students, a regressive loan system whereby the poorest students graduate with the largest debts, and the lowest unit-of-resource for full-time degrees in the UK as well as a cap on the number of Scottish-domiciled students. Wales’s student maintenance package is the most generous in the UK, with higher headline figures and a mixture of grants and loans but loan debt has increased for all students, including the poorest – especially since 2018. Northern Ireland has the lowest tuition fees but the second lowest unit-of-resource after Scotland. England has the highest tuition fees, no grant aid, a regressive loan system but the highest unit-of-resource in the UK.

Common among all four parts of the UK are the increasing use of income-contingent loans, for tuition fees and / or maintenance. England now plans to extend incomecontingent loans through the introduction of the Lifelong Loan Entitlement, which aims to provide more flexible funding for full, part-time and modular courses at Levels 4 to 6. But income-contingent loans remain largely unchallenged. Policy documents consistently portray income-contingent loans as fair and progressive, with equitable outcomes.

They are considered equitable because those who benefit financially from higher education contribute towards its costs when they can afford to, reducing risk aversion in higher education decisions. Income-contingent loans are deemed progressive because higher earning graduates repay more and are subsidised less by government, than lower earning graduates. Income-contingent loans are seen as positive with equitable outcomes because they help remove up-front cost barriers to higher education. They are regarded as efficient because debt recovery (via the tax system) and administration costs are low. Additionally, income-contingent loans can encourage access and widening participation, help fund higher education expansion and protect the sector’s financial sustainability.21 Thus governments tend to perceive incomecontingent loans as benign transactions while simultaneously encouraging indebtedness and normalising it as an ‘investment’ in future earnings potential. However, this is not necessarily how indebted students or graduates experience student loan debt.

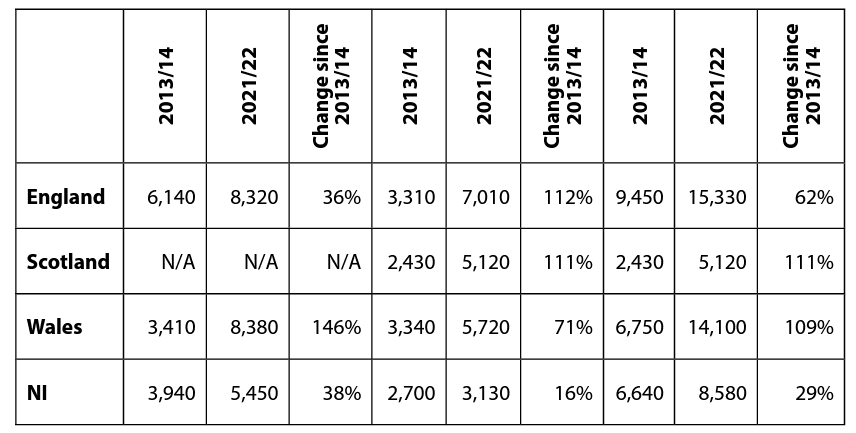

UK governments’ increasing use of income-contingent loans has resulted in students’ growing dependence on loans to fund their studies, rising loan take-up rates and mounting levels of student loan debt. For instance, in England in 2020/21, 94% of full-time undergraduates took out loans, up from 81% in 2009/10, with the wealthiest far the most likely to be debtfree. 22 Average annual student loan borrowing for both tuition and maintenance have increased significantly across all UK jurisdictions since 2013/14.

Changes in average annual student borrowing in the UK, 2013/14-2021/2223

Outside Northern Ireland, the rise is particularly marked for maintenance support, but the 2018 Welsh reforms have contributed to considerable increases in tuition fee debt too.

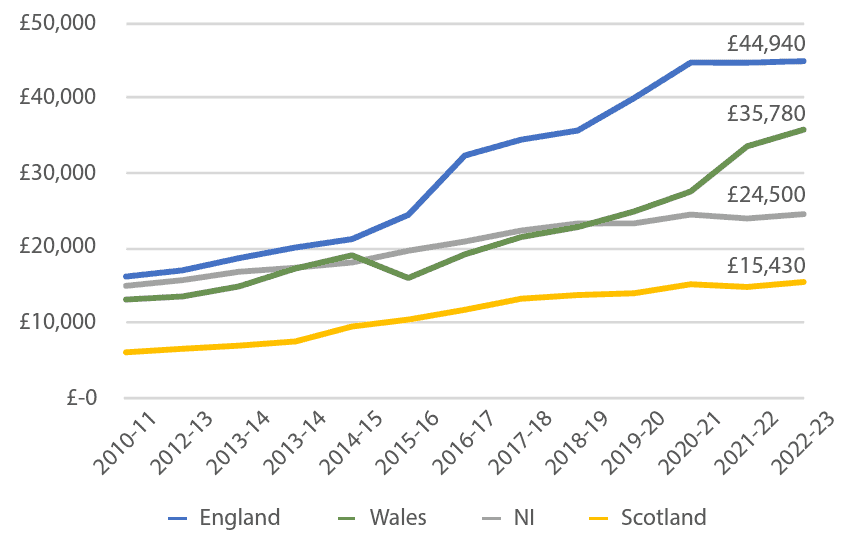

Unsurprisingly, given England’s lack of grant aid and high tuition fees, England boasts the highest average levels of borrowing and debt (not only in the UK, but throughout the OECD).24 English students graduating in 2022/23 had student loan debts averaging £44,940, three times the amount owed by those graduating in 2009.

These average debts are far higher than those experienced by Welsh (£35,780), Northern Irish (£24,500) or Scottish (£15,430) students.25 It will take English students longer on average than their UK peers to repay their loans.

Average loan balance on entry into repayment in the UK – 2010/11 to 2022/2326

Research suggests prospective students’ higher education decisions about whether to enter higher education, and where and what to study can be shaped by the prospect of income-contingent loan debt.27 And debt can shape current students’ experience of higher education too.28 Student funding arrangements, tuition fees, loans and debt play an important role in students’ higher education access and choices and in different countries’ overall higher education participation patterns. But the key determinants of higher education lie outside the funding system in students’ socioeconomic background and prior academic attainment.

However, the longer-term consequence of student loan debt for graduates’ lives should not be ignored as they are by governments. Government rhetoric, and most extant research, fail to acknowledge the potential detrimental repercussions of income-contingent loans for graduates’ lives. Emerging evidence from England suggests that income-contingent loan debt is not as harmless for graduates as portrayed by policymakers. Debt adversely affects most graduates’ lives with the impact falling on a continuum. Contrary to policy rhetoric and policymakers’ intentions, the protective features of income-contingent loans only effectively shield a minority from their harmful consequences.29

Income-contingent loans debt can produce and reinforce inequality while inhibiting future opportunities and potential. It can deter postgraduate study; negatively influence graduates’ job and career decisions; constrain housing options; and have direct adverse financial impacts. The debt seems to constrain opportunities and hinder futures. So, while income-contingent loans can open doors, they can shut doors too.

Notes

- Pathik Pathak, ‘Ethopolitics and the Financial Citizen’, Sociological Review, vol. 62 no. 1, 2014, pp.90-116

- These fees, and the £3,000 cap that followed, were index-linked – for ease, initial figures are cited here, other than at points where the specific amount is pertinent.

- Department for Education and Skills, The future of higher education, 2003 http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/pdfs/2003white-paper-higher-ed.pdf

- The amount of maintenance loan students receive varies depending on their household income, where they live while studying, where in the country they study and their age.

- Roger Brown and Helen Carasso, Everything for Sale?: The Marketisation of UK Higher Education, 2013; Sheila Riddell, ‘Scottish Higher Education and Devolution’ in Sheila Riddell, Elisabet Weedon and Sarah Minty (eds), Higher Education in Scotland and the UK: Diverging or Converging Systems?, 2016, pp.1–18 http://www.jstor.org/ stable/10.3366/j.ctt1bgzc6t.7

- Department for Education, Higher Education: Students at the Heart of the System, 2011 https://assets.publishing.service.gov. uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/ file/31384/11-944-higher-education-students-at-heart-of-system.pdf

- Higher Education Statistics Agency, ‘What is the income of HE providers?’, 2023 https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/finances/ income. The comparable 2020/21 figures for Wales were 54% and 17%; Scotland 37% and 27%; and Northern Ireland 37% and 31%.

- https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/ publications/opening-national-conversation-university

- For details see https://www.gov.uk/student-finance

- Maintenance loans were introduced in 2018 but wholly distance learners such as students at the Open University are ineligible for them.

- Claire Callender and John Thompson, The lost part-timers: The decline of part-time undergraduate higher education in England, 2018 https:// www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/The-Lost-PartTimers-Final.pdf

- Student loan forecasts for England https://explore-educationstatistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/student-loan-forecasts-forengland

- Ian Diamond, The review of student support and higher education funding in Wales: Final report, Welsh Government, 2016, p.5 https:// www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-02/highereducation-funding-final-report-en.pdf

- This figure rises to £10,720 for Welsh students studying away from home (excluding London).

- For details, see https://www.studentfinancewales.co.uk/ undergraduate-finance/

- In 2023/24, part time students can get tuition fee loans of up to £2,625 at a university or college in Wales or studying at The Open University, £6,935 at a public university or college outside Wales or £4,625 at a private university or college outside Wales.

- These are capped, currently, at the same level as that set for English universities – £9,250.

- The repayment threshold in 2023 is £25,375 and debt is forgiven after 30 years.

- For details, see https://www.saas.gov.uk/full-time/fundinginformation-undergraduate

- For details, see https://www.studentfinanceni.co.uk/types-of-finance/ undergraduate/full-time/northern-ireland-student/

- Richard Murphy, Judy Scott-Clayton and Gill Wyness, ‘The end of free college in England: Implications for enrolments, equity, and quality’, Economics of Education Review, vol. 71, 2019, pp.7–22

- Paul Bolton, Student Loan Statistics, House of Commons Library, 2022 https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN01079/ SN01079.pdf; Ariane de Gayardon, Claire Callender and Francis Green, ‘The determinants of student loan take-up in England’, Higher Education, vol.78 no.6, 2019, pp.965–983 https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10734-019-00381-9

- Derived from Student Loans Company data https://assets.publishing. service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/1035644/avg-maintenance-loan-paid-by-domicile_2021. pdf; https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/ system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1117159/avg-tuition-fee-loanpaid-by-domicile_2022.pdf

- Note these average figures hide the distribution of debt by students’ socioeconomic backgrounds. Data for all four nations on borrowing by household income are not readily available.

- Student Loans Company, UK comparisons – to financial year 2023, 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-comparisons-tofinancial-year-2023/uk-comparisons-to-financial-year-2023

- Student Loans Company, UK comparisons – to financial year 2023, 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-comparisons-tofinancial-year-2023/uk-comparisons-to-financial-year-2023

- Claire Callender and Geoff Mason, ‘Does Student Loan Debt Deter Higher Education Participation? New Evidence from England’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol.671 no.1,2017, pp.20–48 https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716217696041; Claire Callender and Gabriella Melis, ‘The Privilege of Choice: How Prospective College Students’ Financial Concerns Influence Their Choice of Higher Education Institution and Subject of Study in England’, The Journal of Higher Education, 2022, pp.1–25 https://doi. org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1996169; Hubert Ertl, Helen Carasso and Craig Holmes, ‘Are degrees worth higher fees? Perceptions of the financial benefits of entering higher education’, 2013, https://ora. ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:cecc1830-7f28-4c8e-ba91-320ecb44bd48

- For example, Diane Harris, Katie Vigurs and Steven Jones, ‘Student loans as symbolic violence’, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, vol.43 no.2, pp.132–146 https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2020.1771507; Neil Harrison, Farooq Chudry, Richard Waller and Sue Hatt, ‘Towards a Typology of Debt Attitudes among Contemporary Young UK Undergraduates’, Journal of Further and Higher Education, vol.39 no.1, 2015, pp.85–107 https://doi.org/10.1 080/0309877X.2013.778966; Sara Minty, ‘Young People’s Attitudes towards Student Debt in Scotland and England’ in Higher Education in Scotland and the UK: Diverging or Converging Systems?, 2015, pp.56–70

- Ariane de Gayardon, Claire Callender and Stephen DesJardins, ‘Does Student Loan Debt Structure Young People’s Housing Tenure? Evidence from England’, Journal of Social Policy, vol.51 no.2, 2022, pp.221–241 https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727942000077X; Ariane De Gayardon and Claire Callender (forthcoming), ‘Disrupting policy discourse: The negative impact of income-contingent student loan debt on graduates in England’; and Claire Callender and Susila Davis (forthcoming), ‘Graduates’ responses to student loan debt in England: “sort of like an acceptance, but with anxiety attached’, Higher Education

Comments

Add comment