The changing profile and work experiences of higher education staff in the 21st century

- This blog was kindly authored for the HEPI 20th Anniversary Collection by Celia Whitchurch, Associate Professor at the IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society.

- In August, we are running chapters from the Anniversary Collection, supported by Elsevier, as a series of blogs. This piece is the tenth chapter from that collection.

Introduction

The material in this chapter is drawn principally from a research project that I conducted with William Locke and Giulio Marini for the Centre for Global Higher Education (CGHE) on the changing nature of the workforce in UK higher education between 2017 and 2020.1,2 In this research, we sought to capture the lived experience of staff having both academic and professional contracts, reviewing these in the context of trends in workforce patterns shown by the UK Higher Education Statistics Agency’s (HESA) annual staff datasets.

Although the trends represented in numerical datasets provide a neat summary, they do not depict the whole story in terms of the day-to-day lives and aspirations of individuals as they develop their roles and careers. By adding a qualitative dimension through interviews, we were able to understand better the working lives and career aspirations of the individuals who are included in those figures. Findings included an increased fluidity in academic careers and approaches to them, and ways in which individuals negotiated their roles.

Changing academic staff profiles

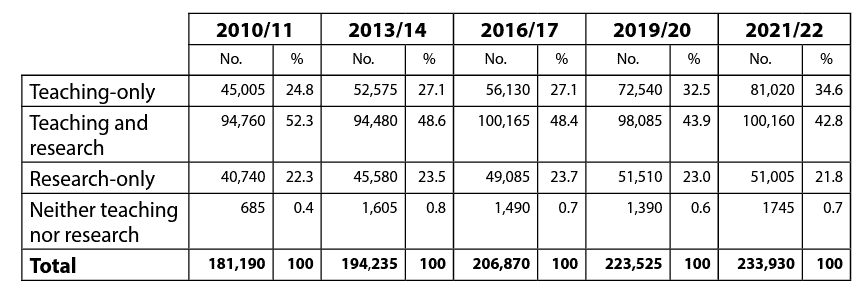

HESA datasets record shifts in the balance of the academic profession over the last decade or so. The number of academic staff in UK higher education institutions increased by 29% in just 12 years, as the table shows. However, the proportion on teaching and research contracts fell from 52.3% to 42.8% during the same period.

In contrast, over the same period, the number of staff in teaching-only roles increased by 80%. Thus, the proportion of total academic staff with contracts described as teaching-only increased from almost 25% to almost 35% between 2010/11 and 2021/22.3 Of those staff who do teach, at the start of this period 32% were on teaching-only contracts, a figure that increased to 45% in just 12 years.

Furthermore, by the end of this period 24% of full-time academic staff and 51% of part-time academic staff were employed on fixed-term contracts.

There is evidence that some of those on teaching and research contracts are being directed to conduct less or no research (or are receiving less or no funding or time allocation for research), and so are effectively undertaking teaching-only roles, despite their contractual status.4 There has also been an increase in the number of academic staff on research-only contracts, from 40,740 in 2010/11 to 51,005 in 2021/22.

Academic staff by employment function, selected years 2010/11 to 2021/225

Teaching-only staff are predominantly part-time (67.5% in 2021/22). However, in the last few years there has been a growing proportion who are full-time, rising from 24.5% in 2014/15 to 32.5% in 2021/22. Although historically the majority were fixed-term, in 2021/22 over a quarter had full-time, open-ended / permanent contracts, compared with 19.8% in 2014/15. Less than a third of those on research-only contracts are on open-ended / permanent contracts, as the majority of these positions are funded from fixed-term research project funding.

Changes in the work experiences of academic staff

Large datasets, such as those provided by the HESA data, help to provide an over-arching map of the sector, but do not necessarily reflect the day-to-day experience of individuals. On the one hand, they provide some evidence for a narrative of an increasingly competitive, precarious and insecure environment, leading to a ‘casualisation’ of the workforce, an erosion of autonomy and a sense of de-professionalisation.6 This particularly affects early career academics who may take longer to establish themselves in the profession, although mid-career academics can also find themselves stalled if they are not research active and have not found another type of role.7 The latter may also have choices to make about the future at a time when they could have increased financial and family responsibilities.8

There are though other narratives at play, and a more nuanced picture has been developed via a number of recent qualitative studies. At the macro level, significant numbers of staff come into higher education from other sectors such as healthcare, business and industry and non-governmental organisations, and others have strong links outside academia, for example, with professional bodies. Some people enter higher education employment later in their careers, and others move in and out. There are, therefore, a variety of entry and exit points, and external activity has influenced profiles across the range of disciplines. Some people use their academic work as a basis for building a portfolio that could provide a bridge to another type of career, such as policy work with professional bodies or non-governmental organisations, humanitarian work, refugee education, the rehabilitation of offenders, child protection or charitable giving.

Academic staff, therefore, act not only as repositories of disciplinary knowledge, but also foster exchange with other forms of knowledge and practice, often in a bridging role. This trend has been reinforced by the requirement for impact in the UK Research Excellence Framework.9 Disciplinary boundaries, as described two decades ago, are therefore becoming more permeable, and stretched by professional practice.10 There is also evidence that, rather than committing to a career in academia, more doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers are considering adjacent roles in higher education, such as research management and administration, or in other sectors. Individuals are, therefore, likely to actively ‘plan, and … construct a way forward [within] given constraints’.11 They do this by navigating the structures within which they find themselves, including job descriptions and workload models. For example, it is not unusual for some academic staff on teaching-only contracts, and other staff employed on professional contracts, to undertake unfunded research; or for those employed on research contracts to negotiate some teaching to gain experience.

At the same time, many universities have introduced new promotion pathways to professor alongside the traditional teaching and research track, and a smaller proportion have pathways focussing on leadership and innovation.12 However, there is evidence that staff on such pathways feel they are less likely to reach the level of a chair than if they were undertaking research. Assumptions about a linear career in higher education, meeting certain goals within certain timescales, are therefore changing. An expansion of roles adjacent to academic activity, such as supporting student employability, community engagement and online learning, have led others to move into new spaces and to adopt ‘concertina-like’ careers, adjusting their activities, and the timescale in which they undertake them, according to their own circumstances.13 Not only do individuals interpret and modify the structures within which they find themselves, but they also create bespoke spaces and pathways, so that broad brush trends identified in HESA datasets can be belied by individual experiences and even contractual arrangements.

A major recent development has been the acceleration of online and blended learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and there has been a general feeling that the time taken in learning new technologies and developing resources to support online and hybrid forms of learning is not accounted for, or at best underestimated, in workload models. Students, and the staff themselves, are likely to need to support with this, putting undue pressure on individuals. Nevertheless, there have also been positive experiences of teaching online, including improved productivity and increased engagement and interaction with less confident learners.14 Thus, wider, distributed learner communities could be established with ‘an ecosystem of learner supports’, consisting of social and personal as well as educational support.15 There is also the potential for such developments to transform ideas about teaching and student engagement to the extent that education-focused roles might be viewed more positively by both universities and the people in such roles, creating more varied career paths. Furthermore, where online communication – either for teaching or meetings – has created opportunities for more flexible working, this could help to ameliorate worklife balance issues and also support greater inclusivity of both students and staff.

Changing professional staff profiles

Perceptions of an increase in what are seen as ‘administrative’, ‘professional or ‘managerial’ staff – defined by HESA as ‘nonacademic’ – at the expense of academic staff masks a complex situation. In practice, HESA’s most recent dataset show that overall numbers have gone down from 217,580 to 192,235 between 2017 and 2021, apart from ‘professional occupations’ (up from 44,975 to 46,700). Major falls in staff numbers include ‘Managers, directors and senior officials’ (11,680 to 9,665), ‘Associate professional and technical’ (48,625 to 43,985) and ‘Administrative and secretarial’ (70,630 to 59,435). The latter are likely to reflect a reduction in so-called ‘support’ staff as a result of factors such as online registration for courses and programmes and the digitisation of records. Moreover, the outsourcing of manual and technical roles may account for a reduction in the ‘technical’ and ‘skilled trades’ categories. The increase in professional occupations is likely to reflect, for example, people supporting online learning, outreach, student study skills and welfare. This growth has been attributed to the priority accorded to all aspects of the student experience in a more marketised environment, as well as a strengthening of central management teams by external appointments.16 It is also likely to reflect a re-badging of some academic staff who may no longer be research active and have taken on these kinds of roles. This may be done to reduce the proportion of non-research active staff returned in the UK Research Excellence Framework, and / or to offer such individuals (and others) an alternative career path.

Changes in the work experiences of professional staff

So-called ‘non-academic’ staff have consisted traditionally of people seen as either ‘specialists’ or ‘generalists’, specialists in discrete functions such as finance, human resources and estates management and generalists primarily in student services, registry and secretariat roles. Generalists in particular were seen as a kind of ‘academic civil service’ and this persisted into the 1990s, particularly in the UK.17 However, a range of other functions have emerged in the last 30 years or so to include, for example, student life and employability, diversity and inclusion, alumni relations, fundraising, research services, outreach and global engagement, often attracting staff who have experience of these types of functions from other organisations and sectors, who may well move out of higher education again as their careers progress. They are likely to see themselves as working in partnership with academic colleagues, rather than necessarily being in a ‘service’ role.

The formal categorisation of roles as found in the HESA data therefore disguises an increase in collaborative working between academic and professional staff across a range of activities, with a blurring of boundaries between them, for example in broadly based fields such as:

- educational development, including academic practice and learning support;

- study skills and academic writing;

- student employability and skills development;

- educational technology and the development of the digital environment;

- support for underserved students and communities, including diversity and inclusion;

- the management of student success;

- promotion of research enterprise, impact, knowledge exchange and transfer;

- data management, analytics, strategic planning and institutional research; and

- public engagement, alumni relations, charitable and humanitarian work.

These developments have led to the concept of ‘third space’ activity within the higher education workforce.18 The people undertaking such roles are likely to have degrees at Masters, and increasingly doctoral, level, and to publish papers about their work. As this concept has gained currency internationally, it is apparent that those working in such areas may go unrecognised in formal categorisations and be dependent on self-identification.

As new areas of activity continue to emerge, there is an ongoing need to develop understandings as to how thirdspace environments, and those within them, might be recognised and progressed within institutions, for example by establishing a ‘third track’ between academic, professional and other progression routes and developing appropriate job descriptions, reporting lines, promotion criteria and career pathways. Furthermore, the developments in online, hybrid and blended learning noted above could lead to a reconceptualisation of teaching in higher education, incorporating a range of contributions to students’ learning and overall educational experiences, including from, for example, counsellors, librarians and specialists in educational technology, study skills and employability initiatives. The acceleration of online and blended learning has therefore highlighted a greater co-dependence between academic and professional staff and could increasingly blur the boundaries between them.

Final comments

The HESA data suggest a fraying at the edges of the concept of a unified academic or professional cadre, with a common experience of linear careers and assumptions about achieving certain career goals within certain timescales. However, the qualitative data from the CGHE study also suggests that, on the one hand, some individuals are increasingly strategic in following a pre-defined pathway, focusing on activities that they believe will bring them credit for career advancement. On the other hand, others – because of circumstances, their backgrounds or specific interests – may take a more bespoke, but less direct career route. In both cases, building a distinguishing self-profile or ‘brand’, often via online media, has been seen as helpful in achieving recognition, particularly by younger staff. In turn, hierarchical line management relationships tend to be regarded as less significant in dayto-day working than lateral networks, including formal and informal mentors. A combination of statistical and qualitative data, therefore, tell a story of an increasingly mixed economy in relation to patterns of academic and professional staff, their activities and their career progress.

A recent HEPI report shows that whereas higher education staff score well on benefits, including pensions, leave and sick pay, compared with other sectors, there are increasing levels of precarity in contractual status, in the form of shortterm contracts, particularly at the early stages of a career.19 Furthermore, our research (which was conducted prepandemic) showed that the ‘early stages’ of a career can last for 15 years or more after a post-graduation doctorate. However, it also showed that there is more traffic in and out of higher education than hitherto, particularly in practicebased subjects, and that an academic role is no longer necessarily regarded as a ‘job for life’, particularly by younger cohorts of staff. It would therefore appear that expectations of a full-time linear career lasting 30 to 40 years are likely to be increasingly unrealistic. At the same time, and despite perceptions of increasing workloads, a job in academia would appear to remain a desirable goal in the minds of those who have achieved a doctorate, at least in the initial stages of a career, although they are more likely to maintain an openness to other possible options.

Acknowledgement

This chapter draws on research that Dr Celia Whitchurch carried out in collaboration with Professor William Locke and Dr Giulio Marini for CGHE Project 3.2, entitled The Future Higher Education Workforce in Locally and Globally Engaged Higher Education Institutions. The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (UK), the Office for Students (UK) and Research England (UK) (grant reference ES/M010082/1) is gratefully acknowledged, along with support from the Centre for Global Higher Education (CGHE), UCL Institute of Education, London, UK.

Notes

- Centre for Global Higher Education, ‘The future higher education workforce in locally and globally engaged HEIs’ https://www. researchcghe.org/research/2015-2020/local-higher-educationengagement/project/the-future-higher-education-workforce-inlocally-and-globally-engaged-heis/

- Celia Whitchurch, William Locke and Giulio Marini, Challenging Approaches to Academic Career-making, 2023

- This total excludes atypical academic posts, ie those members of staff whose contracts involve working arrangements that are not permanent, involve complex employment relationships and / or involve work away from the supervision of the normal work provider.

- Rob Copeland, Beyond the consumerist agenda: Teaching quality and the ‘student experience’ in higher education, University and College Union, 2014

- HESA, Higher Education Staff Statistics: UK, annual series

- Angela Brew, ‘Academic Time and the Time of Academics’, in Paul Gibbs, Oili-Helena Ylijoki, Carolina Guzmán-Valenzuela, Ronald Barnett (eds), Universities in the Flux of Time: An Exploration of Time and Temporality in University Life, pp.182-196; William Locke, Richard Freeman and Anthea Rose, Early career social science researchers: experiences and support needs, Centre for Global Higher Education, 2018 http://www.researchcghe.org/publications/early-career-socialscience-researchers-experiences-and-support-needs/

- Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen, Post-PhD career trajectories: Intentions, decision-making and life aspirations, 2016; Barbara M Kehm, Richard P Freeman and William Locke, ‘Growth and Diversification of Doctoral Education in the United Kingdom’, in J. Jung Cheol Shin, Barbara M Kehm, Glen A Jones (eds), Doctoral Education for the Knowledge Society: Convergence or Divergence in National Approaches?, 2018, pp.105-121 https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10043169/1/Locke_Kehm%2C%20B.M.%2C%20Freeman%2C%20R.P.J.%20%26%20Locke%2C%20W.%20%282018%29%20Growth%20and%20Diversification%20of%20Doctoral%20Education%20in%20the%20United%20Kingdom.pdf

- Celia Whitchurch and George Gordon, Reconstructing Relationships in Higher Education: Challenging Agendas, 2017

- Lord Nicholas Stern and David Sweeney, ‘Institutions must be bold with impact in REF 2021’‚ January 2020 https://ref.ac.uk/about-theref/blogs/institutions-must-be-bold-with-impact-in-ref-2021/

- Tony Becher and Paul Trowler, Academic tribes and territories: intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines, 2001; Mary Henkel, Academic Identities and Policy Change in Higher Education, 2000

- Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen, Post-PhD Career Trajectories: Intentions, Decision-Making and Life Aspirations, 2016, p.4

- Universities and Colleges Employers Association, Higher education workforce survey 2019 https://www.ucea.ac.uk/library/publications/ he-workforce-report-2019/

- Celia Whitchurch, William Locke and Giulio Marini, ‘Challenging career models in higher education: the influence of internal career scripts and the rise of the “concertina” career’, Higher Education, vol.82, no.3, pp.635-650

- Joint Information Systems Committee, Teaching staff digital experience insights survey 2020/21: UK higher education (HE) survey findings, Jisc, 2021 https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/8568/1/DEI-HEteaching-report-2021.pdf

- Charles Hodges, Stephanie Moore, Barb Lockee, Torrey Trust and Aaron Bond, ‘The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning’, EDUCAUSE Review, March 2020 https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-betweenemergency-remote- teaching-and-online-learning

- Alison Wolf and Andrew Jenkins, Managers and academics in a centralising sector: The new staffing patterns of UK higher education, King’s College London, 2021 https://www.kcl.ac.uk/policy-institute/ assets/managers-and-academics-in-a-centralising-sector.pdf

- Albert Sloman, A University in the Making, BBC Reith Lectures, 1963

- See for example, Carina Bossu and Natalie Brown (eds), Professional and Support Staff in Higher Education University Development and Administration, 2018, and Natalia Veles, Optimising the Third Space in Higher Education: Case Studies of Intercultural and Cross-Boundary Collaboration, 2022

- Emma Ogden, Comparative Study of Higher Education Academic Staff Terms and Conditions, commissioned by HEPI from SUMS, May 2023 https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/05/25/comparative-study-of-highereducation-academic-staff-terms-and-conditions/

Comments

Add comment