Always look on the bright side of life? Universities after Brexit

This is a speech that Nick Hillman, the Director of the Higher Education Policy Institute made this afternoon to an academic conference in central London.

Introduction

I have been asked to speak on ‘Brexit: How it will affect universities’. Of course, Brexit has not happened yet and, if there is one thing that all the recent political upheavals have proved, it is that it is more difficult to predict the political weather than it is the actual weather.

So let me start with how universities behaved during the referendum campaign because there are some important things we could potentially learn from it.

The referendum

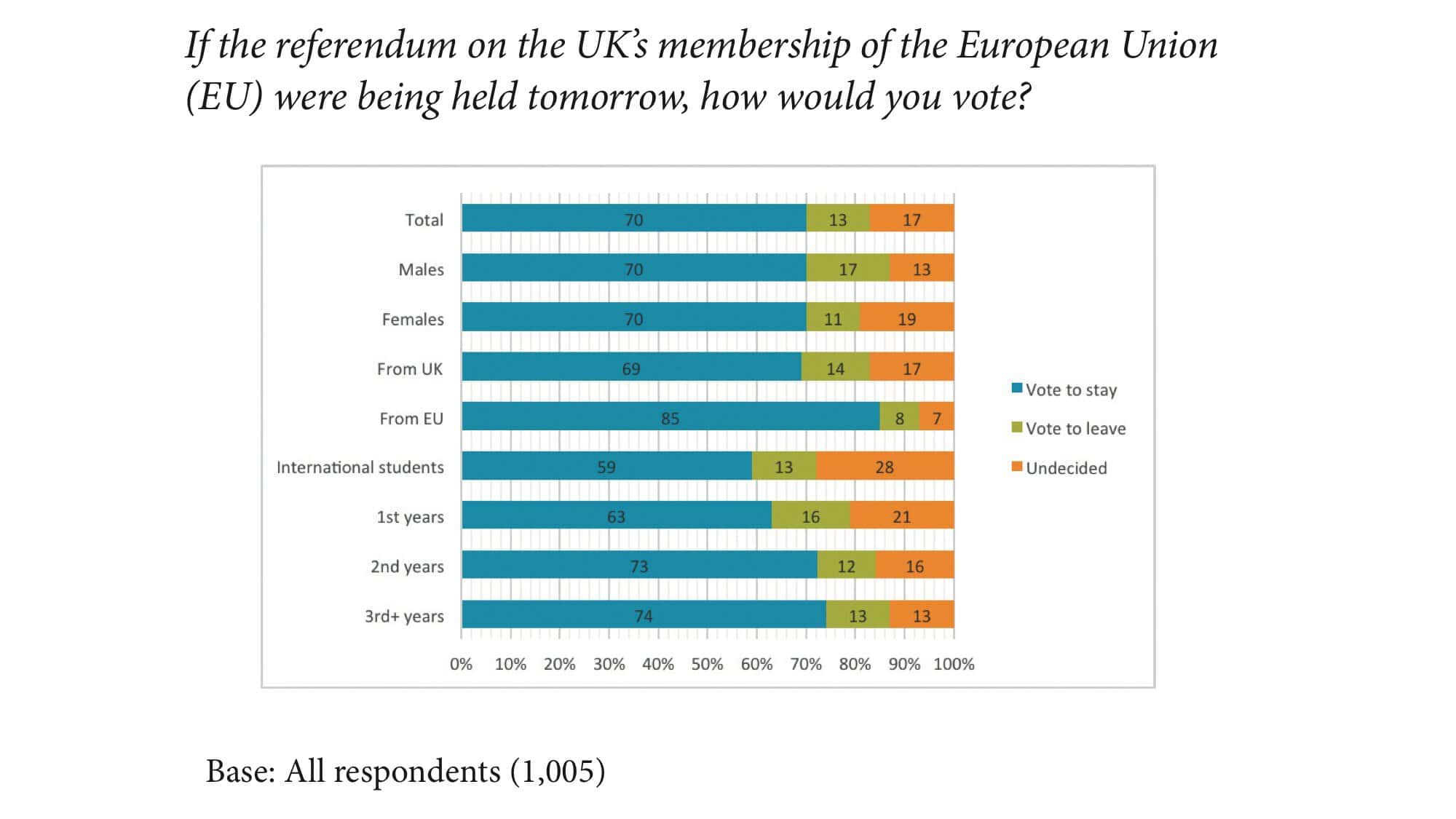

Almost without exception, universities were caught out on 23rd June 2016. Our own data – and that of others – showed the overwhelming majority of staff and students backed Remain. I only know of one person who was a vice-chancellor at the time who admits to voting Brexit – and he was in charge of an alternative provider rather than a traditional university.

Collectively, the university sector ran a big campaign in favour of Remain but, to my mind, it had three major flaws.

First and most problematically, it was inward-looking. As I have already noted, the majority of people on university campuses were firmly determined to vote Remain. Moreover, our data showed the tiny minority who voted Leave had truculent views so were not open to persuasion. Running a campaign aimed at getting people in the higher education sector to support Remain was therefore never likely to make much difference – and, by the way, I made these sorts of points before the referendum so am not just being wise after the event.

Admittedly, a more outward-focused campaign by universities could not, on its own, have convinced 635,000 people who ended up voting Leave to back Remain instead – which is the number that would have been necessary to produce a different result. But, if you read Tim Shipman’s All Out War, which is widely regarded as the best book on the referendum campaign (as I am currently doing), then you realise just how many little things combined to produce the final result.

The second problem with the way the universities campaigned, in my opinion, was that the discussions on campus were rather one-sided. There were debates where no Leave speaker at all was invited or where the Out side was outgunned. I remember attending an event myself at the London School of Economics which was meant to be a serious and intellectual discussion covering all sides of the argument. The European Commission were present, but not a single speaker from the Leave side of the argument was there. At the end, there was a nice warm feeling in the room about what a successful event it had been but no recognition at all that it had been so one-sided.

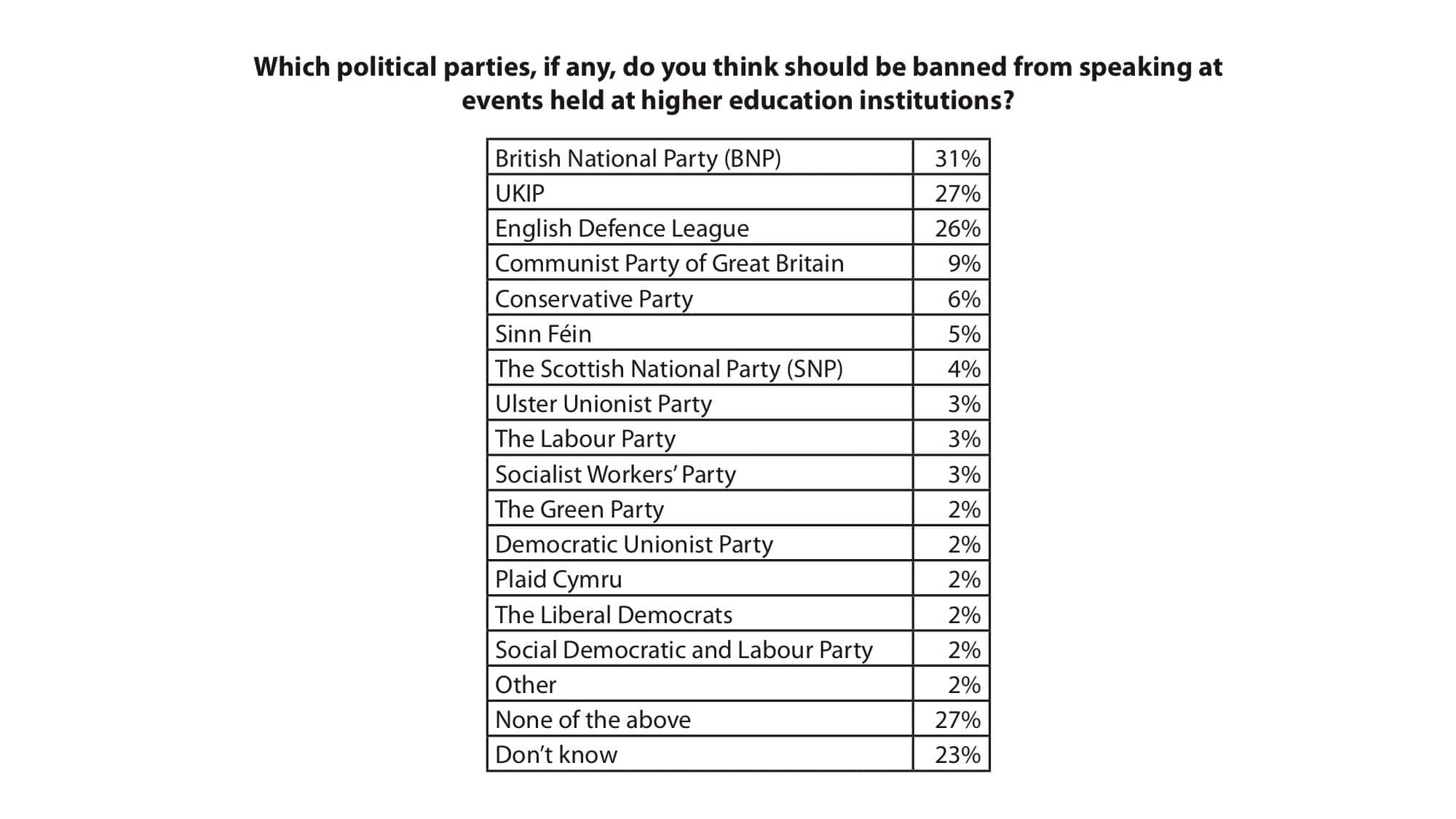

At one with this was a student survey we conducted 18 months ago on free speech issues. We found over one-in-four students wanted UKIP entirely banned from university campuses. Whatever you might think of them, they are a legitimate political party and their growth partly explained the result on referendum day. Failing to engage with them and others on the Leave side of the argument inevitably made the result a shocking jolt to many people in universities when it came.

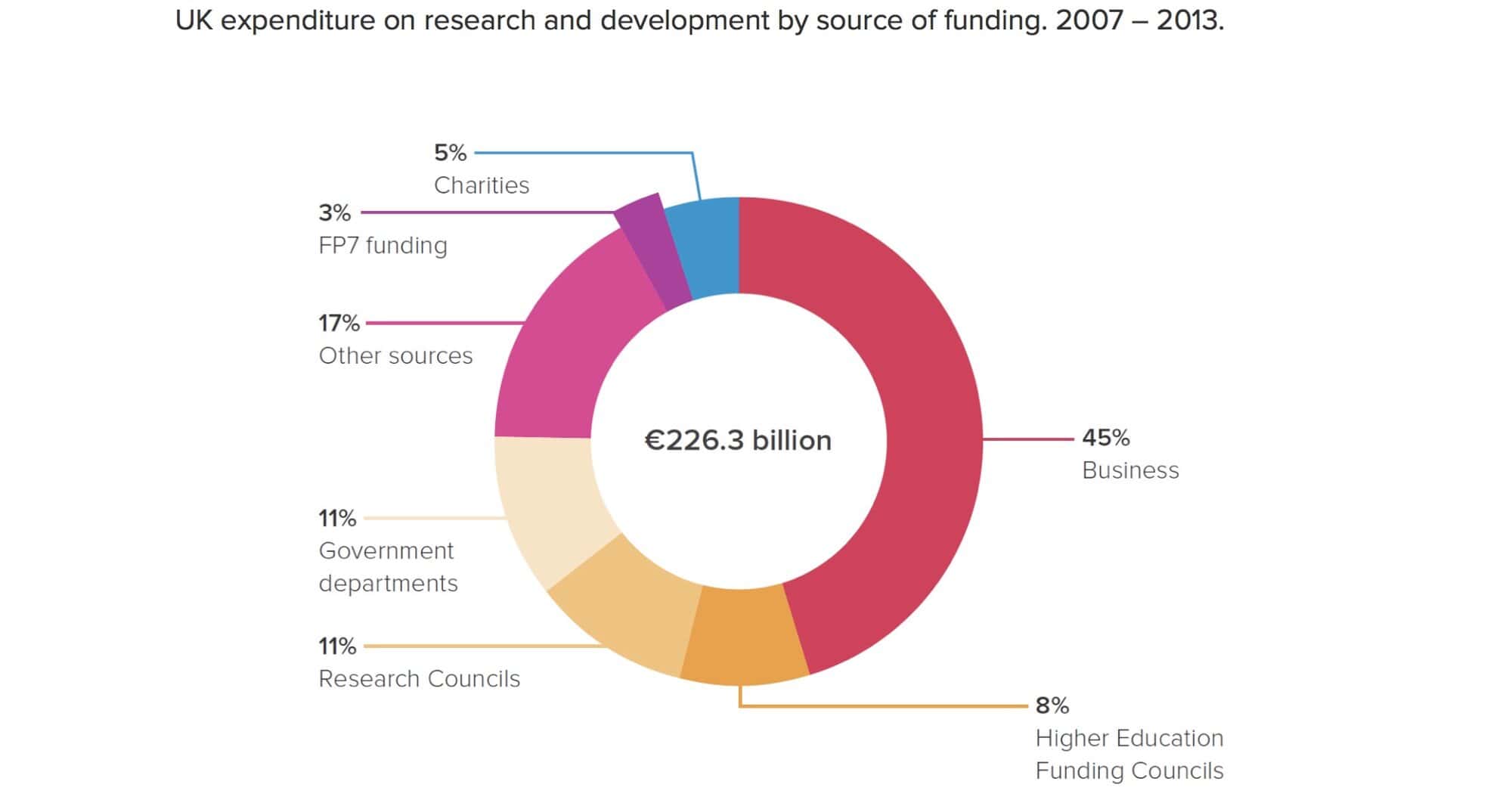

Thirdly, the universities’ campaign was focused too much on money and the amount of EU research funding our universities get. There were various problems with this. For example, while we are a clear net beneficiary of EU research programmes, the total amount of research funding that comes from Brussels is smaller than many people realise – just 3% of total UK research and development spending (according to the Royal Society chart below) and under 15% of total public funding for research.

Focusing on the money played into the hands of the Leave campaign who wanted nothing more than a conversation about cash – witness, the £350 million claim on the side of their bus. It would have been more effective, in my view, to have focused on the purposes to which EU research funding is put – such as curing horrible diseases – and / or on the cross-national collaboration that the money has lubricated, which has had the effect of making British research more successful and more influential. Since the referendum, this sort of argument has become more common but it wasn’t around as much when it mattered most.

I think this recent painful history is worth recalling because it reminds us of the critical importance of universities engaging more in their local communities. Not long after the referendum, we published a paper by Bill Rammell, the former Minister for Higher Education and the current Vice-Chancellor of the University of Bedfordshire, who argued:

[the referendum] has placed a real and significant burden on universities to take a more substantial role in civil society, rebuilding public trust through active engagement and offering accessible pathways to expertise that the public sees as relevant and valuable.

I wholeheartedly agree – and, incidentally, I suspect following this advice may also be the best way to counteract the rash of summer media stories characterising universities as profligate institutions not sufficiently interested in the public good.

But the immediate problem for universities after the referendum was the same as that faced by Whitehall. Because universities shared the Cameron Government’s opposition to Brexit, they did not prepare for it.

So there was no ready answer to the question: you lost the war, but can you win the peace?

In the sector, there were two main fears:

- student numbers would fall; and

- research would suffer.

Let’s take these two issues in turn.

Student numbers

Because so little thought had been given to what would happen in the event of a Leave vote, after the referendum HEPI and Kaplan jointly commissioned London Economics to model the most likely outcome for the numbers arriving from abroad. Our starting point was to assume that the number of EU citizens who come to UK universities would fall as a result of Brexit. In part, this is because they are likely to lose access to tuition fee loans and to face full international fees, which are much higher than the UK fees to which they have been entitled. The latest Ucas figures suggest this shift has already begun to some degree, even though we haven’t actually left the EU yet and even though the Government has guaranteed the continuity of funding for new EU students arriving this year (and next).

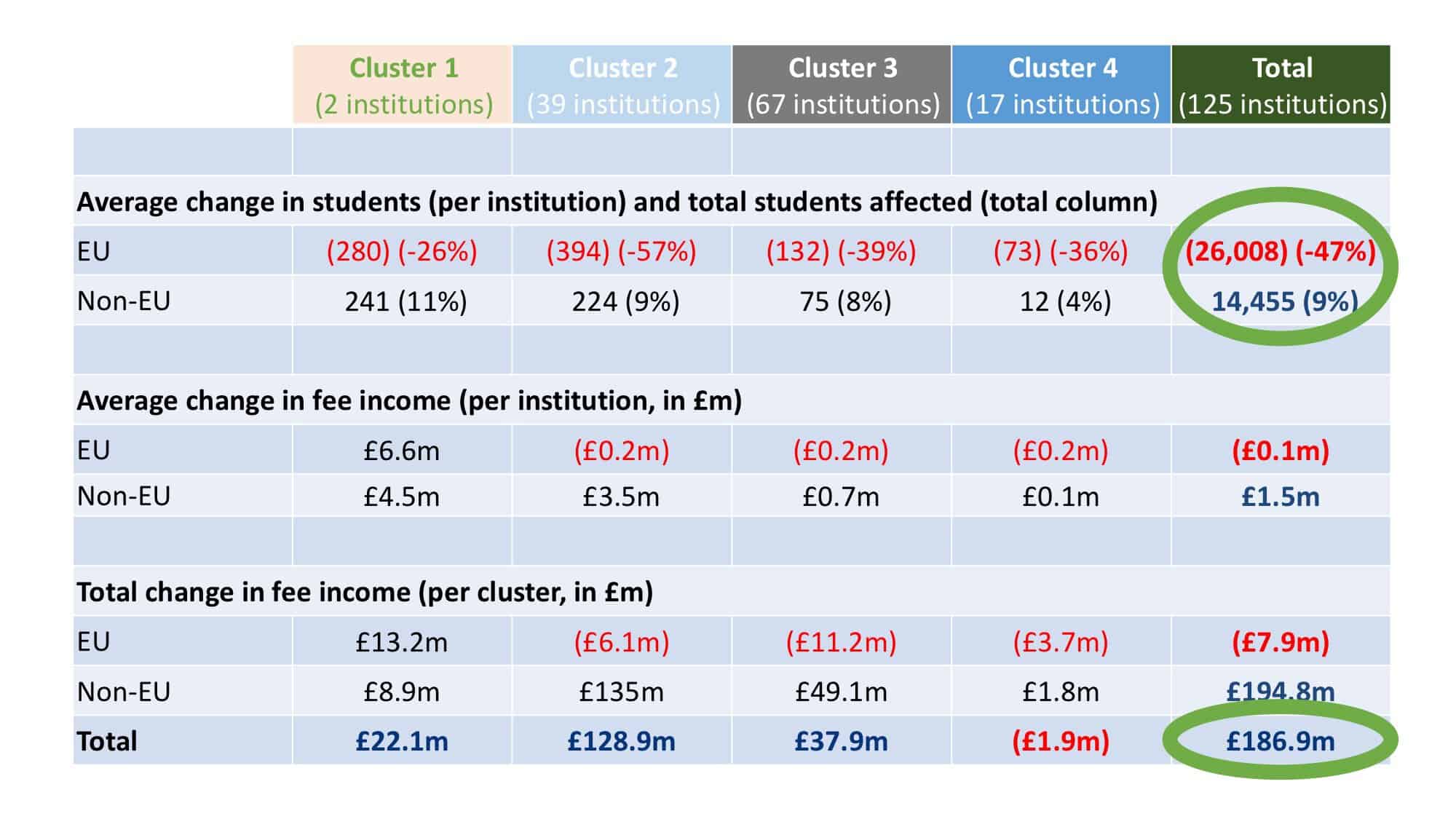

But working out how big the drop-off is hard because it depends on the type, location and mix of students at each university. Our assessment of Brexit’s impact takes such factors into account and concludes the effect on student numbers and university incomes could be significant, but perhaps less dramatic than expected.

There are around three times as many foreign students in the UK from outside the EU as from within it. This is because, until recently, EU undergraduate students came within the student number controls imposed on universities. So there were limited incentives to recruit them. Our analysis shows that, overall, their numbers could fall by 57% after Brexit – that is by over 31,000 new students each year. It is a huge proportion of those who have been attracted to travel from the Continent to study here, but it is still only about 3% of all first-year undergraduate and postgraduate enrolments.

Moreover, because of the higher fees, our modelling suggests that – despite enrolling 31,000 fewer new EU students – universities will only lose £40 million a year in the first year. That is 0.1% of the total income of publicly-funded higher education institutions across the UK. Some institutions, such as Oxford and Cambridge, are likely to see their fee income rise even as their EU students fall. This is because their full international fees are so high and because the appetite to study at the two universities recently declared to be the very best in the world is immense.

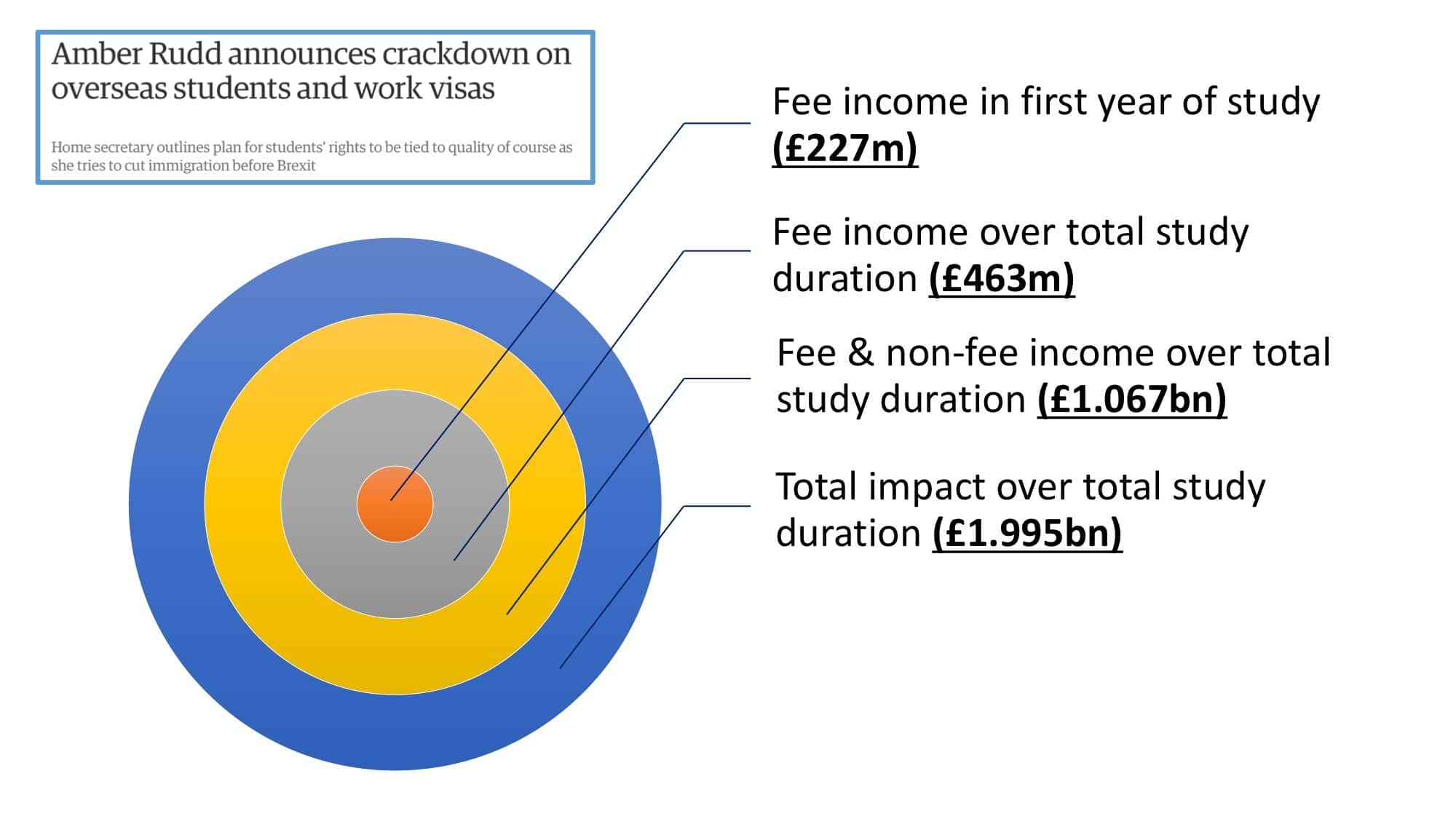

Even that is not the complete picture, because Brexit has led to a depreciation in the value of the pound. That makes studying in the UK cheaper for those outside the EU. Our analysis modelled a 10% loss in value, which we thought could lead to an increase of 20,000 in the number of international students arriving to study in the UK each year, thereby offsetting two-thirds of the fall in undergraduates from the EU. Assuming that is right – and of course as one vice-chancellor pointed out to me there are some ‘heroic assumptions’ in our work – then the income from these additional students’ tuition fees could total £227 million in the first year alone. This would much more than offsetting the financial loss from welcoming fewer EU students.

We concluded the net result would be 11,000 fewer students but £187 million more income. While this is more rosy than many expected, it is important to recognise that it would still mean less diverse campuses, with fewer students from other countries. We may also lose diversity in other ways too: for example, less well-off students from eastern European countries who felt they could only afford to study in the UK because of the access to tuition fee loans will be among those who stop coming.

Moreover, the potential upside in financial terms is not guaranteed to happen. I have long believed the higher education issue on which recent Governments have made the most errors is the approach to international students. We have generally tried to look at the topic from new angles and, over the summer, we published new research on the soft power benefits of educating so many people from other nations, showing more senior world leaders have been in educated in the UK than any other country.

Yet, at last year’s Conservative party conference, the Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, promised ‘tougher rules’ to reduce the number of students arriving from overseas. And, if she were to bar those 20,000 new international students I mentioned a moment ago from coming to the UK, the total loss to the economy could eventually total £2 billion each year. The loss would be split roughly equally between lost direct spending by international students (on fees, accommodation and living costs) and lost knock-on benefits for universities’ supply chains.

That is why the announcement over the summer that the Migration Advisory Committee will investigate the contributions and costs of international students, which we have been calling for for over three years, is vitally important. Indeed, we became so bored waiting for it to be commissioned that we had already started working with the same partners as for our previous Brexit work on calculating new figures for the value of international students to the UK. We expect to launch this in early 2018 and we hope it will feed into the MAC review.

One other thing on student mobility: we need to look creatively for new opportunities to show we understand that higher education benefits enormously from being open to foreign influences. So one policy I have recommended is that any savings from no longer needing to provide student loans to students from other EU countries after Brexit should be reinvested in an outward mobility loan scheme for UK students. In the past, we have been as bad on outward mobility as we have been good on inward mobility.

Research

So, finally, what does Brexit mean for research? Again, we have to be tentative in making recommendations because it depends crucially on how the negotiations go. We can, however, be grateful for the fact that our Government have adopted a very clear joined-up strategy aimed at maintaining a deep and positive relationship with researchers and research programmes across the EU and beyond.

For example:

- In August 2016, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy announced they would underwrite funding for Horizon 2020 projects successfully applied for before Brexit happens.

- In January 2017, the Treasury announced an increase of around 20 per cent in public research and development funding as part of the Industrial Strategy.

- In May 2017, the 2017 Conservative Party manifesto committed to ‘meet the current OECD average for investment in R&D – that is, 2.4 per cent of GDP – within ten years, with a longer-term goal of three per cent.’

- And, earlier this month, the Department for Exiting the European Union published Collaboration on science and innovation, which says ‘Given the UK’s unique relationship with European science and innovation, the UK would also like to explore forging a more ambitious and close partnership with the EU than any yet agreed between the EU and a non-EU country.’

It is also worth noting perhaps that some of the most important cross-Europe scientific programmes are not actually EU ones, including CERN and the European Space Agency. So the biggest European science projects – the ones that scrape the front pages, like the Large Hadron Collider and Tim Peake’s mission to space – are not actually dependent on EU membership or the current negotiations.

So Bill Gates’s claim earlier this week that Britain can still lead the world in science and technology after Brexit is far from completely implausible. There is even an argument that some close observers make that we lost some useful collaborations when we entered the EU, or at least that is what the person in charge of Brexit strategy at the University of Oxford, Professor Alastair Buchan, told the Education Select Committee:

For me, one of the things that we did lose was that nice and easy flow of clinicians and clinician science from Canada, the US, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. We had really good collaborations that hopefully in this Brexit climate might be reinvented, because that movement of English-speaking medicine was a casualty of joining Europe.

That is the positive case for thinking that Brexit will not hamper our research base.

But I have to say it seems unlikely that all the things we hope will happen will actually happen. In other words, it is hard to think that we will simultaneously manage to be:

- a fuller partner of the EU’s Framework Programmes than any other non-EU members; and

- that Brexit has no knock-on consequences for non-EU research initiatives rooted in Europe; and

- that ending freedom of movement will have no negative impact on who comes here to conduct research; and

- that we are able to reinvigorate research relationships with the rest of the world concurrently with negotiating Brexit.

After all, as the Government have themselves admitted in relation to Horizon 2020, ‘Associated countries do not have a formal vote over the work programme, but can attend programme committees, which provides them with a degree of influence.’ A ‘degree of influence’ is a long way from a full place at the table.

Conclusion

So, overall, it seems as if Brexit need not be the disaster for higher education that many people thought it was bound to be. There is an analogy here with all those dire economic predictions from George Osborne, Mark Carney and others about what would happen if people voted for Brexit. They have yet to turn out to be true in full.

But there is a world of difference between saying that Brexit need not be a short-term disaster and saying that Brexit will be a success that makes the UK richer, more productive, better at higher education, more innovative and more globally connected.

Indeed, the risk, as Janan Ganesh, the first-rate columnist in the Financial Times, noted the other day is that the extra challenges we have given ourselves lead us to a path of relative decline:

As performance director of British Cycling, David Brailsford attributed his success to the ‘aggregation of marginal gains’. He sweated technical details that were trifling on their own terms because they added up to a meaningful competitive edge over time. Britain should worry about the aggregation of marginal losses. Citizens of a certain age will know the routine. It ends around 2035 as the average Briton, perhaps standing in the infinite non-European queue of a Mediterranean airport, looks around and notices something about the French and German travellers. They are not just collecting their bags already, they are noticeably better off.

That is a more sober and probably more likely outcome than some of the more positive ones I have discussed.

But it is not inevitable either.

Comments

Add comment